15-Year vs. 30-Year Mortgages (Part 1): Fun with Pix and Historic Data

Tuesday, December 18, 2012 at 11amBy John Friedman

A few days ago I wrote about the difference between tax-deferred retirement accounts and tax-paid retirement accounts, and commented about how the difference between the two is akin to a choice between instant gratification (for TDAs) and delayed gratification (for TPAs).

So how about taking that same framework to mortgages?

And, when doing so, how 'bout in this Part 1 we take a look at FRED pictures and have a look at how to make 'em tell a story? And then how about in Part 2 we take a look at whether a 15-year mortgage might be a better fit for you than a 30-year mortgage?

Sound like a plan?

* * *

It used to be that interest rates on 15-year mortgages were about half a percent lower than interest rates on comparable 30-year mortgages. And sometimes they were only a quarter of a percent lower.

In the past year that spread has been as high as 7/8ths of a percent (0.875%) and is now about 5/8ths (0.625%) (the stock market stopped using eighths and sixteenths and thirty-secondths years ago; the mortgage market has not yet done so).

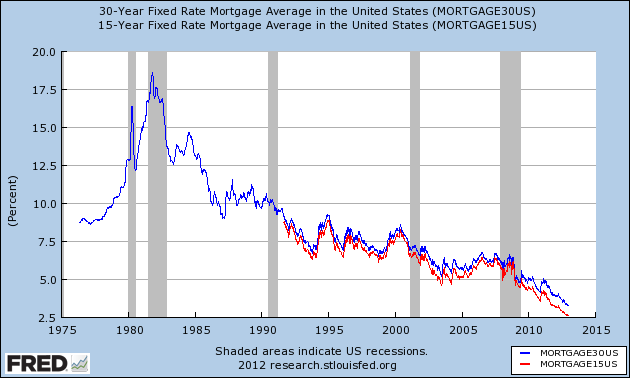

Here is the pic, courtesy of Uncle FRED, using all the data FRED has, this particular cold morning in December 2012:

Remember, the title shows the full name and code-name of the data sets included in the pic, while the legend shows the color-coding of the lines using the code-names.

Here 30-year mortgage rates show in blue and 15-year show in red.

Ah, you say, but the data set for the 15-year rates is much more recent in origin.

Ah, yes, I say in response, different sorts of mortgages have proliferated over the years and back in, say, the 60s, it was pretty much one-size fits all — a 30-year fully-amortizing mortgage.

Wonky aside. The word "amortizing" means that your monthly payment obligation on the mortgage stays constant throughout the life of the mortgage, and is equal to the exact amount necessary to pay off the mortgage in full after the entire period. Believe it or not, keeping the payment constant like that and then hitting the nail on the head at the end of the mortgage means that, every single month during the mortgage, a different portion of your monthly payment goes to pay off interest that accrued in the previous month, which in turn leaves a different chunk of your monthly payment that month that can go to pay down the mortgage debt you owe to the bank, with payments early in the life of the mortgage going almost entirely to paying off interest, and payments later in the the life of the mortgage going almost entirely to paying off the mortgage debt you owe to the bank.

And, yes, your eyes ain't lyin' when you see the horrendously high interest rates in the late 70s and early 80s, nor when they see that interest rates since then have been trending down down down down down.

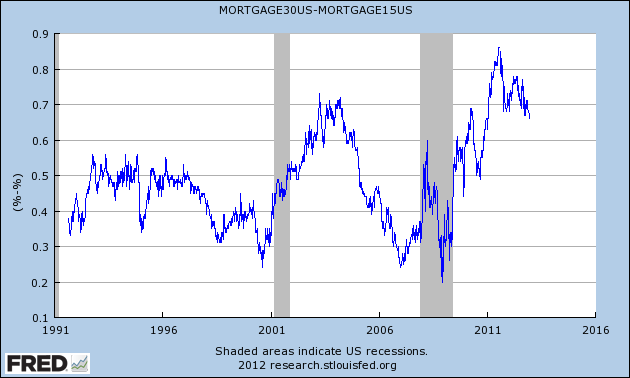

So let's look at the data sets for the period only during which both data sets were up and running, OK? That'll give us a better look:

What'd'ya see? Take some moments to look around in there.

One thing to notice is that the red and blue lines sometimes touch — once in the 1993-or-so range and maybe again in the 2008 or so range — but probably never cross. I say "probably" because pixels can only show so much detail. FRED, if I were to take the time, will serve up all the numbers that together compose those lines, and then put them into a nice, tidy Excel sheet of my choosing, at which point I could then see for-sure whether the lines ever crossed. But today is not the day for me to do that.

Most importantly, I can eyeball that the blue line of late seems to be a lot further above the red line than it has been in the past.

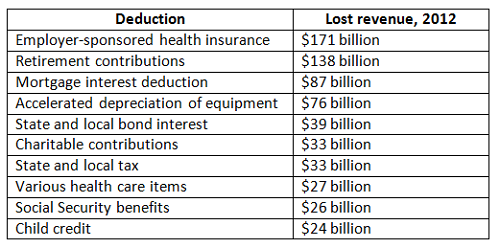

Let's have FRED show us what that looks like, shall we:

Now we have arrived at a truly helpful picture. I went into FRED and told it to subtract out the 15-year mortgage interest rate from the 30-year mortgage interest rate, for any given date, and to then draw the spread — in finance-speak, differences between interest rates are typically called spreads — for all the dates.

Interest rates on mortgages are tantamount to their price. Do you see why?

And right now it looks like banks really want us to take 15-year mortgages — or to at least give them a long hard look, eh? — because the banks have priced 15-year mortgages far more attractively than usual.

* * *

15-year mortgage rates, then, look relatively sweet these days — not far off their very most luscious.

So should you consider a 15-year mortgage?

The answer to that question will have to wait until Part 2.

Hint and Foreshadowing: Are you more of a heart-driven person or a head-driven person? If you’re more head than heart, then the 15-year might be just the ticket.

Further Hint and Further Foreshadowing: Are you more of a low-monthly-payment sort of person or more of a least-expensive-mortgage-possible sort of person? If you’re more of the latter than the former, then, again, the 15-year beckons.

Update: Here is Part 2.

762 words (less than an eight-minute read sans links)

Roth Accounts: The Most Underused, but Very Useful, Retirement Tool

Friday, December 14, 2012 at 12pmBy John Friedman

During the 12/12/12 concert a few nights ago I was double-screening — with the big screen tuned to one of the many networks showing the event and the little screen tuned into my own little slice of the Twitterverse.

It’s always interesting to see non-music folks commenting on music. One politics-oriented tweeter said that she thought the Beatles were the most over-rated band of all time — this while Sir Paul was struggling to hit the high note in the first line of Blackbird, about that chunk of the 24-hour period when the Blackbird sings and it’s dark outside.

She is so very wrong, I thought to myself. I’ve half a mind to tweet back to her that she is full of it, and that the real over-ratee on the show was Commander, not-quite-a-Sir Eric of Clapton-on-Thames, who for the past forty years has been playing the same lick over and over and over again, which is bad enough, but all the worse when the lick he’s been playing over and over and over again wasn’t all that interesting the first time through (compared to, say, Jeff Beck on a bad night) — although, admittedly, Commander Eric of C. does have an amazingly beautiful, doing-it-the-hard-way vibrato (his guitar truly can weep) and he totally has the blues scale down cold.

Besides, we all know that the reason the Beatles were what they were was because of the fellow who’s been gone now for 32 years as of 4 days ago, plus a very gifted, non-show-off’y, reverse-handed can-play-drums-inside-of-Beatles-music drummer, plus perhaps the best guitar-accompanist of all time, plus, yes, Sir Paul. The magic was in the mix, and in the songs, which, lord uh mercy, sure did have sophisticated harmonic structures to them and a great combination of the saccharine and the acrid.

But that’s a lot more than 140 characters, right?

Ah, but this whole thought path did get me thinking about how some things are over-rated while others are under-rated, and also how some things are over-used and others under-used.

And the next thing I knew I was thinking about how Roth retirement accounts are both under-rated and under-used, and then a-writing I did go.

* * *

The government, by way of the tax code, provides us with various sorts of vessels in which to stow our stored-up money. There are flex dollar accounts and there are ESPP accounts, both of which represent short-term waystations where some of our salary dollars cool their jets until we use them for some tax-advantaged purpose within a year’s time or less. Many people have never heard of these things. Not to worry if that’s you (though do ask . . . they are important things).

And then there are the long-term vessels, most of which are retirement accounts which some of us have heard a whole heck of a lot about and most of us have heard at least a smidgen about. You know: the pension plans, the IRAs, the 401k plans, the 403b plans and all the many others making up the veritable smorgasbord of qualified (i.e., for normal folks) and non-qualified (i.e. for big-earners) retirement accounts.

All of them, however, fall into two basic camps: they are either tax-deferred or they are tax-paid. So I split out all the smorgasbord entrees into two camps: TDAs, which are Tax-Deferred Accounts, and TPAs, which are Tax-Paid Accounts. And then I label all the other sorts of investing accounts as TTAs, which are Totally Taxed Accounts, which, at least for the next 17 days, are not-taxed-very-much-at-all accounts.

Caution: I might have made up these abbreviations. If you use them elsewhere, people might look at you funny and not understand what you’re talking about. Go forth carefully with them.

Why Vanguard is the Best All-Around Financial Services Provider for Most Folks

Thursday, December 13, 2012 at 2pmBy John Friedman

When I was younger I had all my dentistry done at the U.C. San Francisco School of Dentistry. I did that because the price was right, and because I had more time on my hands than money.

Sitting in that chair, with my mouth propped open and dressed with dams and nip-tuckers and such, staring up at the dots in the drop-ceiling acoustic tile, trying to count them when I was especially bored, I had a lot of time to think. This was way pre-iPod. Why, it was almost pre-Walkman!

I like having my teeth worked on by folks not at all driven by profit-seeking, I thought to myself. The students here are motivated by just two things — by their desire to learn and by their desire to impress their professors — which is great, especially since their professors are judging them by the quality of their work rather than by their speediness. They’re taking their time and being careful, and they have a watchful eye over them.

* * *

I left my dental-school teeth-care ways behind many years ago now, and have been going for quite some time now to a dentist in Ess Eff Sea Eh whom I really, really like (ask me if you’d like to have her name — she’s near Union Square).

It took many tries to find that dentist, though, so I had quite a few dentists and dental assistants look at my teeth (that is, after all, the main thing they do all day long, right?), most of whom would see one piece of work in there in particular — an on-lay, courtesy of UCSF School of Dentistry — and say that it was a very, very impressive piece of handiwork. I felt abused afterwards . . .

I well remember getting that on-lay. It took many visits and many hours, and I very much liked the student who did the work. She came from a family of dentists and had a good combination of being very intense about her work while also being very friendly and good at the person-to-person level.

I liked her and her services so well, in fact, that I sought her out when I stopped going to UCSF dental school, and was happy to learn that she had set up her own practice in San Francisco after graduating some years earlier, so I started using her services. Wouldn’t’ch’ya know it, though, that after being a patient at her office for less than a year, I left because it was, overall, the worst experience I’ve ever had at a dentist.

What changed?

* * *

Vanguard has now twice asked me to spend a few minutes filling out an online survey telling them what I think of them. I’m fond of Vanguard as a company, so, after the second request, this morning I went ahead and did just that. Very few companies would get any of my time for this task.

I send a lot of folks to Vanguard. The main reason I do so is also one of the answers to one of the questions on the survey, which was, What can we do to have you continue recommending us? or something along those lines.

My response was, Continue being the least evil of the FSPs (by which I meant Financial Services Providers, an abbreviation I was happy to see them use in the survey as well).

Vanguard was smart enough to provide a decent-sized text box, so I continued, Better yet, continuously improve your ability to help people — your ability to do-good.

* * *

Vanguard is a one-off sort of FSP. We don’t have time to go into all the detail about why this is so, so I’ll just point to one aspect of its uniqueness: it is, kinda, a non-profit. Technically it is not, as best I know, a not-for-profit organization as seen in the eyes of the IRS, the arbiter and be-all of that designation at the federal level.

But it is most assuredly an FSP that is not trying to maximize its profits in the way that most of them do, which is to try to absolutely and unconditionally and any-which-way-we-can maximize them.

Now please don’t get me wrong: I’m all for profit. I get it. I’m an MBA for Pete’s sake.

But I’m far more interested in working with businesses that seek to optimize their profits rather than maximize them.

Optimizing just about always comes from building mutually satisfactory relationships within your customer base over the long-run. Think about some local vendors whom you see face-to-face on a regular basis and are happy to support, even if their prices might be a bit higher than some mega-whatever can charge. Hopefully a few come to mind for you.

Maximizing profits, on the other hand, can come from many things. It can come from taking each customer as far up his or her willingness-to-pay curve as you possibly can as often as you possibly can (there’s that MBA-brain showing up . . . ). Think about the airlines and their unbundling of every service other than flying you from Point A to Point B. Are you willing to pay for having your luggage possibly lost and having to wait an extra 20 minutes (if you’re lucky) sucking on jet fuel vapors waiting for the carousel to make you happy before you’re able to get to where you’re going? Some folks are.

Profit maximizing can also come from making it difficult for your customers to leave you — on locking your customers in, who then in turn will allow you to raise your prices. Why do you think banks are so happy to have you set up all your regular payments in their electronic bill-paying systems? Maybe because it’s a real PITB (need I flesh that abbreviation out for you?) to up and move to a different bank and put all that information all over again into a new bank’s bill-pay system?

Profit maximizing can also come from not caring about ever doing repeat business with anyone, so all you care about is having a customer who can pay you now, and hopefully through the nose at that, because you’ll probably never see him or her again. Think of . . . hard money lenders and loan sharks, and think of tow truck operators who get your mommy-van out of the surprisingly deep sand that a dashed-road-on-the-map eventually turned into at the bottom of a hill in Joshua Tree.

And it can also come from being extraordinarily good and extraordinarily unique at what you do. Think of Apple in the iPod to iPhone to iPad Jobsian era.

* * *

Apple folks would, I think, unhesitatingly find this statement to always be true:

Our goal is to provide the very best products and services, and we’re happy to charge very high prices for those products and services regardless of how much money we have in the bank.

Likewise, Vanguard folks would, I think, unhesitatingly find this statement to be true:

Our goal is to provide very good services at as low a cost as possible, and if we ever have more money in the bank than we could possibly need, we’ll look for ways to give that back to our customers.

So the V-folks ask:

What’s the least we can charge for this and still be in business with it?

And the A-folks ask:

What’s the most we can charge for this and still be in business with it?

One is right-neighborly, the other right-business’y, I reckon.

Which do you prefer?

* * *

Now, admittedly, this is over simplified. But like a good financial model, there’s a lot to be said for simple.

Financial Services Providers and their customers both benefit from scale. So you cannot Mom and Pop your way into an FSP that both thinks of you in a neighborly way and has the full ability to do what you need it to do. You need an FSP that’s big (why else would the Big Four Banks of BofA, Wells, Citi and Chase be thriving and the credit unions not?)

There’s only one FSP out there, that I know of, anyway, that has both the scale and the neighborly, optimize-not-maximize approach to their dealings with you: and Vanguard be thy name.

Ironically enough, the one thing that Vanguard is not in any way, in a literal sense, is neighborly, because Vanguard does not have branch offices. Your dealings with Vanguard will therefore be technologically-mediated (this is a fancy phrase for over the phone or via the Internet) and entirely with people living in Pennsylvania — Malvern for the headquarters, as well as the surrounding environs, all of which are within an hour’s drive of Philadelphia PA. Even if you live next door, though, as best I know you cannot just drop in and be customer-served.

So if you’re wondering which FSP to use for investing, and you have your choice, and if you are OK with them not having a branch near you, to my way of thinking there’s only one place to go, and that would be Vanguard.

* * *

Full disclosure: Vanguard is the main FSP I use for investing and the main FSP I recommend for self-directed investors. Other than by way of being a customer of Vanguard, I have never received anything of value from them. In fact, I pay them quid-pro-quo for the value I receive as their customer, so, in a sense, I have received nothing from them whatsoever. They’ve never even taken me out for coffee, let alone to lunch.

About 1600 words (less than a twenty-minute read sans links)

P.S. Here is a list of FSPs that Vanguard asked about in the survey, wondering whether I used any of them. When I look at this list, I see fewer than 10 that I would ever even consider recommending to someone.

| A.G. Edwards |

| American Century |

| American Express/Ameriprise |

| American Funds |

| Bank of America |

| Barclays |

| BlackRock |

| Charles Schwab |

| Citigroup |

| Dreyfus |

| Edward Jones |

| E-trade |

| Fidelity |

| ING |

| iShares |

| Janus |

| JP Morgan Chase |

| Merrill Lynch |

| Morgan Stanley/Smith Barney |

| Oppenheimer |

| Pimco |

| Prudential |

| Putnam |

| Scottrade |

| T. Rowe Price |

| TD Ameritrade |

| TIAA-CREF |

| UBS |

| USAA |

| Wells Fargo |

| Credit union |

| Other (please specify) |

The Decades Leading up to Retirement: Where Should You Be?

Wednesday, December 12, 2012 at 12pmBy John Friedman

Recently I’ve had several conversations with 30-somethings looking to me for help in improving their overall financial health.

Happy feelings ensued. It’s every financial planners’ delight, I say to them, to see people your age smart enough to be getting into action on improving their overall financial health with the help of a financial planner. Most people wait a lot longer . . . and some people never do it at all . . .

I say it’s a delight because, at the tender age of 30-something, there is so much future remaining within which to both (a) build a financially healthy life, and (b) alleviate most any ill financial health issues that a 30-something might have accumulated in the past (student debt mostly be thy name, out out you damned spot).

In fact, I sometimes (always know your audience!) add, You can be a total financial-health-train-wreck and still, at your age, be able to lead a great long-term financial life.

* * *

Retirement planning is the Big Kahuna of financial planing. It’s the one thing that’s on the mind of most everyone who works for a living: will I be able to retire?

Years ago I put together a picture to help answer that question. The picture illustrates two trajectories of what our financial lives typically look like, at the numeric level, as we steer (and sometimes veer and careen and bob and weave) our ways towards financially healthy retirements. The picture scales everything to multiples of annual spending. So, for instance, the picture answers the question, At any given age, how much should I have saved up, stated in terms of how much I spend each year, if I want to retire when I’m 65?

Here’s the picture:

For specific instance, looking at the Pretty Darn Safe green columns, the pic shows that a 30 year old person spending $50K per year (a bit more than $4k per month) would be doing quite well trajectory-wise to have about half that amount stored up, while a 50 year old person earning that amount would be doing just fine, thank you very much, having stored up about $350k.

I can just hear some of you out there saying to yourselves, Ahhhh, to be 30 again.

* * *

Here are some drill-downs on, and add-ons to, the pic:

The 4% and 6% Rules of Thumb. The pic is based — loosely — on the much-debated 4% rule of thumb; that approach is depicted in the Pretty Darn Safe set of columns. To this I added my very own (at least I think I might have made it up) 6% rule of thumb; that approach is depicted in the Close to the Bone line.

Spending in Retirement. The pic mostly fluffs the question of how much people spend once they retire. The old financial planner line of thought was that you’d spend less on dry cleaning, and that somehow your reduced dry cleaning bill, along with some other factors, meant that you’d spend less overall (I’ve worked with some dry cleaners, and they don’t make nearly enough money to explain that old line of thought).

My advice to people is quite different: I advise them to expect that they’ll spend at least as much when they retire as they spent right before they retired and that, at least while they are still able to be active, they’re likely to spend more than that, especially if they have the travel-bug and they don’t like roadtripping-and-cheap-motel’ing it.

So, too, with income taxes: the pic fluffs the issue of whether income taxes are included in the spending scalar or not. This topic can cut both ways in this model; do you see why that is?

Pensions, Medicare and Social Security. The pic ignores pension, Medicare and Social Security benefits. If you know someone with a pension (largely limited these days to people who worked for the government), then you also know how big a something that is to ignore. Good ol’ fashioned pensions are truly wonderful retirement vehicles for lots of folks. We should all have it so well (and I do mean that literally).

As far as Social Security goes, I count myself among the yaysayers rather than the naysayers. I find the Social Security system to have been a smashing success so far, and believe that Congress can make it long-term healthy with a few tweaks along the lines of what Ronald Reagan and Tip O’Neill did during the 80s — if the Ps-that-B (the Powers that Be) let ’em.

Medicare and Medicaid, on the other hand, because they ride on top of our enormously broken healthcare system, are themselves broken; they’ll likely be just fine if we ever manage to get our healthcare system itself healed. Healthcare system, heal thyself.

Medical and Long Term Care Expenses. Medical expenses and long term care expenses (also known as nursing home expenses or assisted living expenses or convalescent home expenses and the like) in our later years are huge topics. Let’s talk about them some other time, shall we?

On Models Generally. Like many financial models, the model embedded within the picture above is an unabashed lie. It will not happen. It more than fibs. Fabricates it does.

The model presupposes, for instance, that life is not change and instead presupposes that life is much more like the rocks: constant and unchanging from any time-frame at which we humans might care to observe it during our lifetimes, with the roller coaster ride that is ownership of financial assets magically (and illusorily) transformed into perfect, geometric, arithmetic CAGRs — into compound annual growth rates (aka constant annual growth rates).

And when was the last time you saw one of those? Our world is instead full of growth rates that are random, arbitrary and capricious: we live in a wild and crazy RAC’y world, not a smooth, calmly-flowing CAGR’y one.

That said, though, the model can well illuminate. Because, as it happens, the numbers typically making up the real-life trajectory of a person’s numeric approach to retirement are, when fully delved-into, what I like to call, in a nasally British voice, wickit complicated. If you were to look at real-life examples, then, you, if you’re a normal person, would likely throw up your hands and say, Enough of this and so be it — I’ll just keep on keepin’ on the way I’ve been doin’ it. Out you damned numbers all over the place, out.

Models are the antidote to this predicament. Yes, they surely round the edges and dodge the details, but in doing so they can help you see. Just please do be careful that you not take them literally.

* * *

So how about all the twenty-somethings out there? Am I saying that they should party like it’s [fill in your chosen year — 1999 sounds so last century].

Yes, kinda I am. There’s plenty of time to get fully underway with accumulating and building up financial wherewithal. And — gee — there’s only one decade when you’re in your twenties, newly minted and living life independently for the first time (for most of us). Plus, the odds are that you’ll have plenty of time to live long and prosper.

And am I saying that if you’re in your 50s and you’re way Way WAY behind both trajectories shown in the pic that you’re SOL? No. But I hope you like what you’re doing for a living! Because the best way to make a retirement work (pun intended) is to love your work so much that your idea of retiring is to do less of your work but to continue doing your work and to continue bringing money in through your endeavoring rather than relying solely on your past accumulations to float your boat.

So try this on for size: see what you can do to become (or what you can do to remain for all time) one of those lucky, love-my-work-and-can’t-stop-doing-it sorts, who, when asked about the idea of stopping their work entirely, usually responds with something along the lines of, Are you kidding me? Are you outta your cotton pickin’ mind? Why on Earth would I do that? I love what I’m doing, and I’m getting better at it all the time, and really, really, really want to see just how far I can take it. So why would I do that?

Here, then, is my main retirement advice, suitable for every person who does not have a fortune saved up big enough to for-sure float their boat for time immemorial, and regardless of which decade of life that person might be in: find something that you can’t *not* do, and be lucky enough to have that certain something pay well enough to float your boat, and then enjoy it and use it well.

Because, when you have that sort of endeavoring in your life, the numbers will always number-out just fine and to your liking.

And because, with that sort of endeavoring in your life, you’ll be so very much more happy — and so very much more financially healthy — as you make your way towards your later years.

About 1500 words (less than a fifteen-minute read sans links)

PostScript: The kitty was kind enough today to deign to add her own thoughts on this topic. Here they are, with some punctuation, by way of gaps, to assist those of you who are small-screen-readers, provided by her felinal assistant and grammarist, moi:

33333332 2222 2222222222 22222222222222 2222222222222222222 2222222222222 22222222222222 2222222222 333323

Today’s Rorschach Test: The Federal Government’s Money-In and Money-Out Numbs

Monday, December 10, 2012 at 11amBy John Friedman

And here’s to you, you billions and trillions of dollars that is the federal government’s Money-In and Money-Out. A nation turns its lonely eyes to you.

Do you know what those numbers look like?

Most people do not.

* * *

One of the most long-lived financial sites aimed at self-directed investing folks is The Motley Fool; it’s been around for nearly twenty years, which makes it about a hundred years old in financial-site-years.

A few days ago one of the Fools at Motley Fool (and, yes, that is what they call themselves endearingly), named Morgan Housel, posted some numbers for how much money the federal government has coming in and how much it has going out.

I cannot vouch for the accuracy of Morgan’s numbers. Morgan sites his sources as “Office of Budget and Management; Federal Reserve; author’s calculations” and also adds that his category of “Income security” equals “unemployment benefits, food stamps, etc.”

There is a lot of room in there for some judgement calls and some values-added-in, but I’d be surprised if there is anything stark-raving-mad about the way Morgan put these numbers together. Also, Morgan very helpfully provided some benchmarks for how today’s numbs compare to the averages for those numbs since 1960 (remember: there is a lot of hanky panky that can happen with the choice of starting dates and the like, but nothing here jumps out as a purposefully-chosen number)(that said, a lot of folks go back to 1944, the beginning of FRED-time for many data series)

Thank you Morgan for a great presentation! And for doing some heavy lifting, not the least of which is digging up all those long-term averages, and then there’s also the part about putting together a table that loads well onto various screens, big and small.

* * *

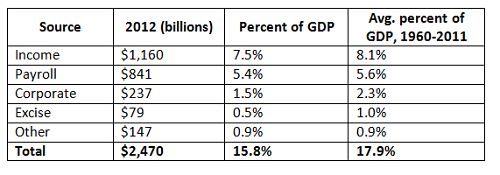

Here is how Morgan sees the federal government’s Money-In (largest to smallest):

As shown here, at least at this level of analysis the federal

government’s Money-In is fairly simple — just five items

And here is Morgan’s take on the federal government’s Money-Out (also largest to smallest):

By comparison, the federal government’s Money-Out is a many-headed thing,

with each line item here representing a whole lot of people

and interests and sharp-elbowers

Yup, if you start with the Money-In and subtract the Money-Out, you see a roughly trillion dollar deficit.

* * *

Morgan also includes a table of what are wonkily known as tax expenditures, which is financial-wonkese for tax deductions that reduce the tax bills of those who use them, and therefore are, in a wonky way, very much like federal government Money-Out (also going from largest to smallest):

Most of these tax expenditures are creatures of the 1040 — they lead to a decrease of personal income taxes paid by BLBHBs — paid by biological, living, breathing human beings, e.g., social security benefits (which for most folks are largely or entirely un-taxed) and retirement contributions (Roth accounts have just not caught on — we are all so instant-grat folks, aren’t we?). But some go mostly to business, such as accelerated depreciation of equipment (don’t ask . . . )

* * *

As an antidote to the mind-numbing that comes about from talking heads spewing characterizations of numbers-based issues without ever backing up those characterizations with the actual . . . um . . . numbers, in here I often do just the opposite: I set out some numbs and then ask you what you see. You can think of this as a numbs-based mind un-numbing.

In here I call these Rorschach Tests, named after the testing technique developed by Hermann Rorschach, a rather dapper fellow by my estimation (click that link to see). In fact, I use this approach often enough that I no longer have to look up the spelling of Rorschach.

The tables above represent, I suspect, the grandest Rorschach Test I’ve put forth in here so far.

Some folks see some of these line items as horrific. Some see some of these line items as the most wondrous of all human responses to the question of how to further our overall well being. And then some folks see all of the line items as one or the other — as all horrific or as all wonderful.

So what do you see?

Are you surprised by anything in there, either because a certain line item is bigger than you thought or because it’s smaller? And do you understand what each of the line items represents (if not, fear not, because you are not alone: the tax code is wicked incomprehensible for most folks, and I am not, in this piece, helping to guide you through that particular layer of complexity).

And what would you cut/increase/modify/obliterate/gargantuate/etc.?

That’s a tough question, especially at the numbers level — at the level of cold, hard facts.

* * *

I just returned from Washington D.C., a city I’ve visited frequently over the past two years. I’ve gotten to know it pretty well.

When in D.C. I hang out with a lot of architects, many of them rather big deals in some way. We talk . . .

Architects focus most of their thinking on the built environment. When doing so, they are usually referring to buildings and streets and houses and the like — the physical world we inhabit, as modified by all of us BLBHBs — the world in which we live, as modified by people-kind, by all of us biological, living, breathing human beings.

Personally, when I think about the built environment, I add another important element to the concept: I add the non-physical world in which we live, by which I mean the society within which we all reside every moment of every day. We did build that.

And when I’m in D.C., I see that society we’ve built as wonderfully beautiful (though, ironically enough, building-wise I see D.C. as not that great, with one 12-story boxy office building after another . . . ).

So as I walk on the National Mall between the White House and the United States Capitol, I see 300 million-plus people within our immediate world who, collectively, now and via their ancestors, created something truly beautiful — far from perfect, yes, but still truly amazing, with many of its imperfections having a whole heck of a lot to do with how it became so truly amazing in the first place, and also having a lot to do with what we BLBHBs are really, truly like deep down inside.

And then, expanding my seeing still further, I see 7 billion-plus people the world over, and I see something more wondrous still, as all of us BLBHBs certainly do have a lot of different ways of organizing ourselves.

Many uglinesses, this place we call home, but far more which is beautiful than ugly, with the ratio getting better all the time

About 1200 words (about a twelve-minute read sans linked–to content)