Being Smart About Picture of Numbs — the Corporations-are-People-My-Friend Edition

Tuesday, December 4, 2012 at 11amBy John Friedman

Many years ago, during a client meeting, I learned anew that there are many kinds of intelligences — that any given person can possess high intelligence of one sort while simultaneously possessing low intelligence of another sort. Since then I’ve come to know in a much deeper way that, in the middle of the bell curve, each of us is very smart in some ways and very not-smart in other ways, all at the same time.

The particular coupling I witnessed first-hand that day many years ago was present within a terrifically successful business person who, though wicked smart in doing business, simply didn’t do well when looking at graphs. The information flowed from the graph to the client, surely, but the knowledge borne by that information was, at best, slow to arise after the information arrived, and sometimes failed to arise altogether.

* * *

Here’s an interesting graph which appeared this morning within the progressives-friendly, astutely-political Daily Kos, nestled within a piece by Laura Clawson entitled, Corporate Profits are Highest-Ever Share of GDP, While Wages are Lowest-Ever:

Looking at this graph, financial wonks and readers of good financial wonkery the world over will well-recognize the . . . let’s call it trade dress . . . of FRED — the light blue frame, the gray verticals showing periods of recession, etc. — which is the Federal Reserve Economic Data site and uber graph-making tool operated by the St. Louis Fed. As a tool held in high esteem by many in the profession and derided by, as best I can tell, no one, FRED is also a testament to the ability of government’y sorts of entities to do good to great work.

So what’d’ya see?

First, notice that Laura had to do some graph-building here. She wanted to show relative values — the percentage of GDP for which corporate profits and wages each accounted. To do that she had to find the data set for corporate profits (called CP in the FRED database) and for wages (called WASCUR in the FRED database), and then she had to tell FRED to divide those data by GDP data (called, simply and thankfully, GDP in the FRED database) . That’s what’s shown in the legend box in the lower right-hand corner of the FRED graph.

Second, she had to get the lines to somewhat overlap so you could compare what they’ve done vis a vis each other. To do this she had to tell FRED to use one percentage-based scale for the corporate profits (shown as decimals on the left-hand axis, and ranging from a 12% maximum to a 2% minimum) and a different percentage for wages (shown on the right-hand axis, ranging from 62% to 42%). This, too, is shown in that legend box in the lower right-hand corner of the graph, via the left and right labels.

I can pretty much promise you that, until Laura dialed in those graph-design parameters and told FRED to re-draw the picture, she wasn’t certain what the graph would look like. She probably had an idea, but, with the pleasure of creation and new illumination, after generating the graph she probably sat there for a few moments and let the information so-delivered coagulate into knowledge so-gleaned. Such is the fun of drawing pictures with numbers!

* * *

Now onto some comments.

1. Smart-Graph-Viewers Look at the Axes and the Labels. When people want to snow you with a graph, one of the ways they’ll do it is to do something funny with the scales they use for axes (that’s the plural of axis, not the thing the TinMan holds up). Oftentimes they’ll chop off the lower part to make a very small change look big, i.e., if a scale goes from 0% to 100% and the data is showing a change from 60% to 62% within that scale, then you won’t see much of the change, but if the scale goes from 55% to 65%, you surely will. So always look at how things are labeled (and, graph-designers, if you want your work to be taken seriously, you should do the same thing as well).

Here that means that it’s easy to overlook the fact that, as shown in the graph, wages are huge relative to corporate profits. Currently, with both measures residing at their extremes, wages represent 44% of GDP while corporate profits represent a mere (a mirror?) 11% of GDP (not the 60% they would appear to be if you incorrectly used the right-hand scale of the graph for both figures). There’s a lot of people in this country of ours, and a lot of ’em are wage-earners. And no doubt there’s a lot of that a lot, as well as many non-wage-earners, who would use the numbers on the right-hand axis to understand both the red line and the blue line, and, gosh a’mighty, would they ever end up with the wrong idea.

2. Smart-Graph-Viewers Look at the Narrative but Draw Their Own Conclusions. Pictures of numbers are often accompanied by some narrative. Here, Laura’s main narrative is encapsulated in this two-sentence chunk:

After-tax corporate profits were a record share of the gross domestic product in the third quarter of 2012. Wages were the smallest share of GDP they’ve ever been.

The link in Laura’s text is to CNNMoney, which is a good way to say, I’m not making this stuff up, since CNN is seen by many as the most neutral mainstream arbiter of facts, poised as the anti-Fox/anti-MSNBC entrant in the true/not-true realm.

If you click on that link, you’ll see an article by Chris Isidore (no link to his bio here because there’s no link in the article to his bio) (bad CNN, bad). Chris’s article has much the same take on things as Laura’s narrative. Nicely enough, Chris also includes a quote from Robert Brusca, widely known (by me, anyway) as the guy who was in the World Trade Center and caught live, on camera, giving an interview when the truck bomb went off in the basement during the first World Trade Center terrorist attack, at which point Robert, feeling that not-then-departed but now very-dearly-departed building take a jolt in a way that made absolutely no sense whatsoever and had never happened before, had the presence of mind, and the good manners and clean-language personality to say something entirely broadcastable, along the lines of, Gosh, what was that?

So here’s Chris’s rendering of Robert’s take on the numbs, coming into view as a result of Laura’s blog posting this morning:

“That’s how it works,” said Robert Brusca, economist with FAO Research in New York, who said there is a natural tension between profits and the cost of labor. “If one gets bigger, the other gets smaller.”

What do you think? Does that explain the graph well?

I’d say that it does so only in part. Do you see why?

3. Smart-Graph-Viewers Decide for Themselves What’s What. So what do you think? Every picture tells a story, yes? So what’s the story here?

We begin with a reprise of the graph, to allow for small screens and such:

What’dy’a see? What’s the story being told here?

First, note that wages (the blue line using the right-hand scale) have fallen from a high of ~53% of GDP in the late 60s to a low of ~44% currently. Remember: you have to look at the scale on the right-hand side of the graph to find the correct numbers to match up with the line.

Second, note that corporate profits have risen from a low of ~3% in the mid-80s to ~11% currently. Again, please remember: you need to look at the left-hand axis to get the correct figures for corporate profits. Note also that corporate profits have been all over the place, especially lately.

And here is the one thing I would do differently if I were the person doing the FRED-surfing today. I think I would compare wages to corporate revenues rather than corporate profits because, in an apples-to-apples fashion, I’d like to track what I call Money-In for both people and corporations, while this graph is looking at something akin to corporate savings (i.e., Money-In minus Money-Out a/k/a profits) and comparing it to personal Money-In alone — a bit apples-to-oranges, that.

Perhaps FRED doesn’t have corp revs?

* * *

And what do I really make of this chart?

I’ve talked a lot in here about capital vs. labor, and how, over the past thirty years, our tax code has strongly favored capital over labor. So when Mitt Romney equated corporations with people, I, like many others, criticized him for doing so because the “people” to whom he was referring are few and far between. Most of us do not feel like those corporations are us. They are other; they are them. Their money is not our money.

In fact, it’s kinda the opposite: their money is our not-money. Better still, their money is our (money).

But I think all of that misses the point. I think the graph works just as well — better in some ways — with simply the blue line, leaving the red line out entirely and, with it, leaving the whole labor vs capital thing aside for the time being.

That blue line in the graph, all by its lonesome, shows that the wages of people — biological, living, breathing human beings — currently represent a smaller part of our overall economy than during any other period since the beginning of FRED-time, which is 1944. What’s more is that, with a happy exception of an interlude in the late 90s (the beginning of the mass commercialization of the Internet be thy name), wages of people as a percentage of the overall economy have been falling quite consistently since the late 60s.

Why, for many of us, that’s our entire friggin’ life! The whole thing. Yikes.

And for those of us quite a bit older, it’s our entire working life. Sheesh.

What we see here, then, is a very long-term, not-at-all-happy trend — if, that is, you, my friend, are a human being earning wages.

* * *

So who’s gonna buy the goods and services the corporations produce? Sure, the B2B part of the economy — with B2B standing for business to business and the B2B part of the economy being the part of the economy in which businesses buy from and sell to other businesses — is a big part of our economy. But so, too, is the B2BLBHB part of our economy — standing for business to biological, living, breathing human beings.

The buying that all us biological, living, breathing human beings — us BLBHBs — do at WalMart, for instance, constitutes a sizable, 1.7% chunk of the overall economy (the data and the arithmetic are that, in 2010, WalMart’s revenues in the U.S. consituted a bit more than a quarter of a trillion dollars which, in a bit less than a $15 trillion economy, amounted to about one-sixtieth of the economy, or nearly 1.7%).

In turn, WalMart paid some of that money out to other businesses in the B2B world, but also to every last one of its 1.4 million U.S. employees as wages. All of those employees, presumably, bought from WalMart using their employee discount and spent lots of money elsewhere as well.

The wages those employees receive from WalMart in exchange for their labor are, as is often reported, at the low end of the scale, as WalMart has slaked the thirst present in most everyone (but by no means everyone) to pay as little as possible for every single thing they buy and, in doing so, put together a truly gargantuan business which, at its heart, pays as little for everything as it possibly can — and then, seemingly, pays a bit less even than that.

So you can find WalMart on both sides of the B2BLBHB span: its revenues are the B side of the B2BLBHB part of the economy, and the wages it pays out to its employees are on the BLBHB side.

One side, though, has grown like all get out for decades, and the other has shrunk. Their relative pieces of pie have changed a lot.

And one side is calling the shots, and the other not so much. Thus to the victors the spoils of capitalism do go. But has it gone too far? That is a topic for a day other than today. The graph, though, has something to say about it.

* * *

All in all, then, and as shown via FRED, in whose data we do most sincerely trust, and as guided by the very capable FRED-turning of Laura Clawson, it’s clear that us BLBHBs — all of us biological, living, breathing human beings — have, relatively and piece-of-the-pie speaking, a whole lot less money coming in via our day-to-day endeavoring than we used to, while the Bs have been, by and large, and with some fairly short-lived exceptions, doing just fine, thank you very much.

At some point those sorts of machinations and tightenings-of-the-screw create problems and then rupture. You can call it The Great Recession or The Lesser Depression or The Decimation of the Middle Class or The Election of 2012 if you like, or, maybe, just maybe, somewhere out there in the future we’ll know that the real rupture had yet to come and we’ll have a name for that which awaits us out there.

For now, though, we can see with some clarity and say with some factyness that during the last five years the Bs as well as the BLBHBs suffered, but one much more so than the other, while one, if you believe my dear friend FRED, seems to have been doing worse for the better part of all of our lives.

All, of course, relatively speaking . . .

About 2300 words (less than a twenty-five minute read sans links)

The Golden Gate and the Gun: Two Equally-Easily-Deadlies?

Monday, December 3, 2012 at 11amBy John Friedman

The Twitterverse is abuzz today with talk of Bob Costas’s Sunday Night football comments about guns. The context for those comments, briefly, is that a day or so earlier a professional football player in Kansas City named Jovan Belcher had allegedly shot and killed his girlfriend, with whom he had parented a three-month-old daughter, and had then driven himself to his team’s practice area, where he then, after thanking some of his coaches for their support and help and while still in their presence, proceeded to shoot and kill himself.

The predictable Rorschach Test has ensued. Gun control folks see this as a great time to argue for gun control; guns rights folks see this as a great time to argue for guns rights.

Courtesy of Real Clear Politics, here is the transcript of what Costas had to say:

Well, you knew it was coming. In the aftermath of the nearly unfathomable events in Kansas City, that most mindless of sports clichés was heard yet again: Something like this really puts it all in perspective.

Well, if so, that sort of perspective has a very short shelf-life since we will inevitably hear about the perspective we have supposedly again regained the next time ugly reality intrudes upon our games. Please, those who need tragedies to continually recalibrate their sense of proportion about sports would seem to have little hope of ever truly achieving perspective. You want some actual perspective on this? Well, a bit of it comes from the Kansas City-based writer Jason Whitlock with whom I do not always agree, but who today said it so well that we may as well just quote or paraphrase from the end of his article.

“Our current gun culture,” Whitlock wrote, “ensures that more and more domestic disputes will end in the ultimate tragedy and that more convenience-store confrontations over loud music coming from a car will leave more teenage boys bloodied and dead.”

“Handguns do not enhance our safety. They exacerbate our flaws, tempt us to escalate arguments, and bait us into embracing confrontation rather than avoiding it. In the coming days, Jovan Belcher’s actions, and their possible connection to football will be analyzed. Who knows?”

“But here,” wrote Jason Whitlock, “is what I believe. If Jovan Belcher didn’t possess a gun, he and Kasandra Perkins would both be alive today.”

Ted Nugent, well-known gun-liker and large-game-killer, had this to tweet in response [sic for all of these tweets]:

Hey Bob Costas we all kno that obesity is a direct result of the proliferation of spoons & forks Get a clue

And then there is this tweet from someone with 133 followers (which, in the Twitterverse and Twitterese, means that the fellow is not at all a thought-leader and is just a common-Joe sort of fellow), nicely summarizing the polarity and the Rorschach’yess of the whole thing:

I literally disagreed with everything bob costas said

So where do you find yourself on this one? What do you see when you look at this Rorschach?

* * *

In my experience, the guns-rights issue is right up there with abortion and the death penalty in terms of how black and white the issue is for most folks, with very few people placing themselves in the middle.

Fairly many people — a shocking number, in fact — do, however, place themselves in the middle of the Golden Gate Bridge and then jump off. Few survive the 200-plus foot fall and, if they did, most would drown in the cold and roiling waters the bridge spans. Because, forget The Beach Boys and summer fun and forget Southern California, which is hundreds of miles away; remember, instead, that the waters touching Ess Eff Sea Eh are always wicked cold, suitable for children under ten only, and not for all of ’em, and then only up to their knees (and please do be very careful of the waves, both regular and rogue, as well as of the undertows and such . . . ).

So very many people take the jump, in fact, that we here in Northern California have gone through a decades-long debate about whether to install suicide barriers on the bridge. Lovers of the beauty of the bridge — if you’ve never seen it, you really should ’cause it’s a real beauty! — do not want to see the look of the bridge changed.

Some of those who’ve had loved ones breathe their last breath while falling from the bridge fight for the barriers, arguing that the look of the bridge would be little-changed and many lives saved. It’s an attractive nuisance, they say. If it wasn’t so easy to jump off that bridge, and so top-of-mind, my child would still be alive. So please, let’s put up barriers and save lives.

So how many lives would suicide barriers save? It’s hard to know for sure, but estimates are that someone jumps off the bridge about every other week, making it one of the top handful of places in the world where people decide to live life’s last. So, if you assume that the suicide barriers would be 100% effective, they could save as many as a couple ‘a dozen folks each year from approaching and then succumbing to that deadly nuisance that some see when they see the Golden Gate Bridge.

Here’s what the rest of us most fundamentally see:

* * *

And here’s what I know. Forks and spoons are for eating, the Golden Gate Bridge is for getting to the other side, and guns are for hurling a little piece of metal fast enough and hard enough to penetrate whatever is in the path of that little piece of metal as it makes its physical way to its ultimate resting place, regardless of consequence and regardless of where that resting place is and what it has to go through to get there.

And I know that forks and spoons also allow people to eat too much, the Golden Gate Bridge also provides a handy and quite majestic place to live life’s last, and guns also provide a way to involuntarily take the life of another being.

And when I look at that Rorschach image, I see that, of those three things, one is not like the other. One of those three things is far more easily deadly than the others. And with respect to someone other than (usually) the intended direct-user of the thing, one of those three things is also more involuntarily-easily-deadly than the others.

* * *

When you look out at the world, do you see a WAITT world or a YOYODED world?

Or both?

On one hand, we’re all in this together, living in a WAITT world (in Jared Bernstein-ese). In a WAITT sense, there are ways to bend the curve — at least some — on how many events like the Jovan Belcher shooting happen (not to mention the Aurora movie theater shooting, the Columbine high school shooting, the Tucson shopping center shooting, etc, etc., etc.), while also not impacting Nugent’s hunting hobby, and not leading to a world in which only the criminals have guns.

At the same time, there’s no denying that we are all part of a very you’re-on-your-own, very dog-eat-dog world (a YOYODED world in John Friedman-ese — because Jared just goes with the YOYO acronym and leaves behind the much more illuminating, in my opinion, dog imagery . . . ).

So we play hard and we play for keeps; we gain at others’ losses and we make them eat our dust.

In the aggregate, this approach has served us well in many ways. Internationally/economically, for instance, we’ve been indisputable Top Dog for more than a century. And there’s a lot to be said for that.

But, please, can’t we make us dogs, when we get angry or unhinged, a bit less easily deadly? Because, after all, we really do inhabit the same place, and we really are on this journey together. And, who knows? The you who is on your own might be the you who is staring down the barrel of a gun some other you has half-a-mind to use in a way that your you would would really rather that other you not pursue.

So how about we aim towards a world in which the most physically aggressive act a fellow dog could hurl at your you would be a vehement, gut-felt growl, followed by a quick turn and a walk-away?

We have centuries to get it right, but sooner than that would be nice.

* * *

Thank you, Bob, for saying what I view to be the truth, and an inevitably-true truth at that.

Now can you please talk to NBC and convince them to not screw up the Olympics?

* * *

Full disclosure: I haven’t directly known any GGB suicide jumpers, but, in unrelated instances occurring over the last decade, loved ones of two friends of mine have jumped off the bridge. I view the bridge differently as a result, and it wouldn’t surprise me if I never walk on it again.

One thousand words exactly (before I wrote this wordcount ending) — about a ten-minute read sans linked-to- content

Luck vs. Skill: The Whitman Example

Wednesday, November 28, 2012 at 2pmBy John Friedman

I knew folks at eBay while it was going through the steep part of the hockey stock — which is SiliconValley-ese for growing like all get out, the imagery being based on the shape of a graph of the revenues (and hopefully profits) of a company experiencing hyper-growth, with dollars (preferably big dollars) on the left axis and time (preferably short amounts of time) on the bottom axis:

I was at E*TRADE during the steep part of its hockey stick. It was a blast and a half to be there when it was growing that fast — and so much more fun than what the last five years have been like for most folks. But it can also be the worst of times because growing that fast can make the company’s culture quite chaotic, resource-grabby and shark-like.

My impression of eBay back then was that it was the first truly irresistible Internet business. People who liked to shop for used goods couldn’t get enough of it — and there are a lot of those types of folks (look at all the thrift shops we all support) — so eBay’s business took off like a rocket ship and kept at it for years and years and years.

* * *

So how hard was it to steer that rocket ship? Ho much skill did it take?

Meg Whitman was at the helm most of that time, and the conventional wisdom back then was that she was brilliant — Proctor & Gamble marketing genes let loose in the new Internet body.

Whitman left eBay in 2007 and, since then, she hasn’t looked all that brilliant.

In 2010 she ran a campaign to become governor of California against Jerry Brown and to replace Arnold Schwarzenegger. After initially looking like a contender, and after spending tens of millions of her own dollars (uhm, on looking it up . . . make that perhaps as much as $160 million of her own dollars . . . ), the race wasn’t even close: Whitman lost 54% to 41%, by 13 percentage points.

I don’t follow stocks or business as much as I used to — it used to be one of the main things I did. But that was then and this is now.

Today, however, I did have occasion to look up how the company Meg Whitman has been involved in for the past nearly two years has been doing. That company — the once-venerable and now consistently-Keystone-Cop’y Hewlett Packard — has an accounting scandal on its hands; it goes by the cool-tech name of Autonomy. And to my mostly-untrained ears, it sounds to me like HP has not handled the whole thing very well (not to mention that they paid more than $10 billion to acquire this company based in the UK called Autonomy, which is a lot of money to pay for anything, but a truly wicked amount of money to pay for an accounting scandal).

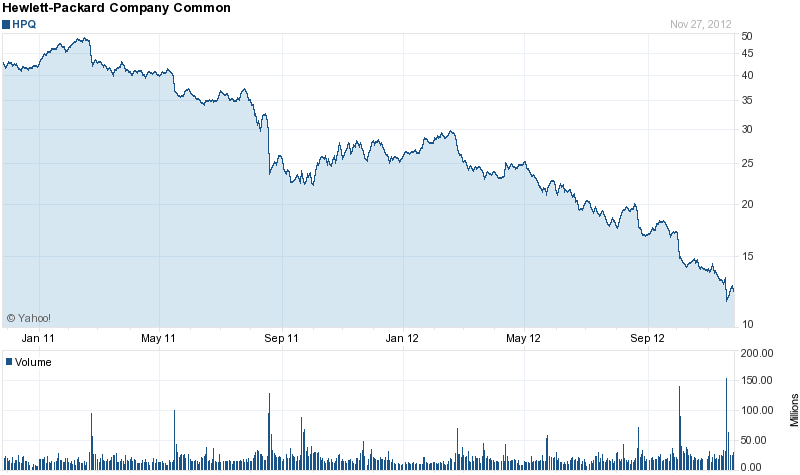

Here’s what the share price of HP stock has done since Meg Whitman got onto its board of directors in January of 2010 and then, nearly a year ago, took over the joint:

Not good, eh? Why, if you just look at the blue line from September 2011 and on, it kinda looks like a flipped-over hockey stock, doesn’t it?

Especially when you consider that the American stock market as a whole during that time went up about 20%, this chart isn’t generating any warm, appreciative feelings among HP shareholders. Relative to the background hum of the market, HP, with Whitman’s board involvement and then under her leadership, has performed to the tune of a negative 75% (here’s the arithmetic: if you had put $100 into the market as a whole back then you’d have about $120 today, but if you had instead put that $100 into HP shares, you’d have about $30 today, so you’d be $90 worse off, and $90 is 75% of $120).

* * *

In economics, both macro and micro, there are no controlled experiments. We live in but one time-line, and to do a controlled economics experiment, we would need to have two or more. True, you can sometimes find analogs and the like, but you can never run a nice clean experiment comparing what would have happened if, say, Obama’s stimulus package had been twice as big as it was. It’s just one of those no-can-do things.

And then there’s also that correlation is not causation thing.

So we cannot do a double-blind, beautifully designed experiment comparing eBay with Whitman from March 1998 through November 2007 against a control group of eBay sans Whitman from March 1998 through November 2007. Nor can we do that for her still ongoing, and far less happy, HP tenure.

So we can’t know, with any certainty, whether Meg Whitman is a great CEO or a terrible CEO or something in between.

* * *

But we can say this: it was probably a whole lot easier steering a company like eBay, which was taking off like a rocket ship and whose sheer growth could mask many foibles (eBay’s failure under Whitman to purchase PayPal earlier than it did is one that comes to mind . . . ) than it is to steer a company like HP, which is sinking like a stone and, unmasked, parading its many scars for all to see. Maybe her star-CEO status, derived from Rocketship U.S.S. eBay, was more than a tad overdone then?

And we can also say this: she was at least adequately skilled on the relatively easy CEO job, while thus far she has shown herself to be something short of a miracle worker on the exceedingly difficult CEO job. And clearly she was not terrifically skilled as a politician.

So how about luck? Was she lucky on eBay?

For sure luck played a role — it always does.

But drilling down, what can be said about luck’s role in Whitman at eBay? There she steered a rocket ship. Steering anything takes some skill; having that which you’re steering, though, be a rocket ship that just wants to stay a rocket ship for years on end takes a good deal of luck and sweet fortune (no pun intended), as well as some right-place/right-timing it, for which she deserves credit.

And you also have to give her credit for having the gumption to take on the HP beast, which has been in a world of pain, in some ways, seemingly ever since Messrs. H and P stepped down. There’s that story about how that Q got onto their ticker symbol . . .

But when you combine the not-good-at-all political outing with the very not great results so far at HP, you have to wonder whether eBay is Whitman’s outlier storyline and, the others, the fat part of the curve.

Of course, Michael Dell ain’t doin’ so great either, Ted Waitt now appearing to have had, in some ways at least, the better product . . .

About a thousand words (roughly a ten-minute read sans linked-to content)

It’s Not Like Going to the Dentist

Tuesday, November 27, 2012 at 11amBy John Friedman

I talk about human nature a lot in here. I must, because, if your goal is to help people improve their overall financial health — as mine is — then your route lies through at least one human being, and that human being is chock-full of human nature.

Most often the context in which human nature comes up involves slack-cutting, with healthy doses of forgiveness and thankfulness (t’is the season!) thrown in for good measure. The slack-cutting comes about from the difficulty with which many of us approach the endeavoring involved in explicitly and actively seeking to improve our overall financial health, as human nature makes many of us less powerful in this endeavoring than we are in many of our other endeavorings. Because it just so happens that, for many of us, there’s just something about crawling up inside our financial lives that makes us not want to do it, as in, I just don’t wanna.

So it’s a slack-cutting — with a good, end-oriented purpose — we do go.

* * *

The conversation goes something like this:

You have a car, right?

And you wash it, yes?

How often? Once a month? And how long does that take? Half an hour each time maybe?

So you spend something like a half-dozen hours each year washing your car, right?

And it’s not like you accidentally get the car washed, is it? You have to go out and do it, don’t’ch’ya? So all-told that’s six hours per year of you going out there and getting it done, either in your driveway or at a car wash, yah?

And how much time do you spend doing the equivalent thing with your financial life — taking care of it and maintaining it and such?

Hmmm . . . so is your car more important to you than your financial life?

Yea . . . I didn’t think so . . .

* * *

And then the forgiveness comes from understanding that the person who takes better care of his or her car than his or her financial life is simply human and not entirely culpable for acting in that way, while the thankfulness comes from knowing that that very same human-ness can be turned, in just the right way, into a force for good rather than a force for non-good — turned back against itself, so to speak, to become an agent of change and doing rather than an agent of non-change and non-doing.

Everyone’s human nature can, then, at the right time and in the right hands, be re-directed in the financial health realm from inertia of rest into inertia of motion.

And from all that comes another layer of thankfulness and marveling, from knowing that we are all, in the aggregate, such amazing, wonderful, adaptable, changeable, improvable human being creatures.

* * *

And then the follow up:

. . . And is that car more important to you than your child’s education? [or retirement, as appropriate]

No?

Yea, I didn’t think so about that one, either.

* * *

Many jokes are told about how we all hate to go to the dentist; we English-speaking-idiom-generators have also had our way with it, as in I’d rather have a tooth pulled than . . . [name your unpleasantness].

Clearly there are exceptions (some folks — me for instance — like having their teeth cleaned). But, in general, if you want to describe something as being terrifically unpleasant, you might well describe it as being like going to the dentist.

Dentists have done a truly wonderful job of getting many of us to take good care of our teeth; we FPers should take notice of how excellent a job they’ve done (and have you ever noticed how our teeth healthcare system works wonderfully when stacked up against our rest-of-body healthcare system?). But they’ve *not* done a great job of curtailing the linguistic and cognitive pairing of going to the dentist with no fun at all.

* * *

Now, I can’t speak for all financial planners and all financial clients out there, but I most assuredly can speak for myself and for my clients, and can tell you that, once they step into a financial planning process with me, just about all of my clients find the process to be quite enjoyable.

This initially surprised me to no end, especially when clients told me, as we ended meetings that focused on spending (the good, the bad and the ugly, with usually not much of the former) that they’d really had fun. The word fun, in particular, caught me by surprise; I was not expecting that. Y’all mean to tell me that talking about how to smarten up the spending part of your financial life is fun?

Since then, though, I’ve seen, time and time again, clients having fun at that meeting, as well as all the other meetings we have.

So it turns out that, fairly often, it’s just plain ol’ fun.

* * *

Fun comes in lots of forms. The fun of doing your financial planning is not like the fun of watching the newest blockbuster Hollywood movie or the fun of a beautiful day at the park with your favorite people. And it’s nothing like the apparent fun had by a dog, tongue a waggin’, head out the window, goin’ down that long lonesome highway.

Rather, for many folks, as they first enter into the financial planning process, it’s the fun of taking a load off — the fun of un-burdening, of finally being in action. That first step — the first step when, often after months or even years of wanting to be in action but instead suffering from complete and utter inaction, someone says, Yes, I’m in, let’s do this — is a particularly happy/fun moment. It can be fleeting as well, though, so in my practice I do my best to highlight that moment for each client, to allow the client to better remember it months and years later, when good pats-on-one’s-own-back have been well-earned. Modern feoffing, you can call it. So there’s a big Big BIG victory upfront, and all that happened was that someone — you, maybe — decided to begin.

It’s also the fun of realizing that the power-to-accomplish that accompanies you into so many other parts of your life need not be a stranger in the financial part of your life, and, in fact, can come right on in and be right handy in there.

For couples, it’s also the fun of doing something very couple’y, very much about long-term love and growing old together; it’s a fun romance of a sort of thing. And, when wee ones are involved, it’s also way about them, and that really brings home to roost the fun and the significance and the taking-care-o’-my-own-and-can’t-wait-to-see-what-they-will-soon-become feeling, n’est ce pas?

And it’s also fun born out of a darker side, as, for belly-of-the-beasters, it’s also the fun of finally crawling up into the belly of the beast that is their financial life and starting the process of taking it by the horns to corral it into submission.

For just about everyone, it’s also the fun of realizing that it’s not at all complicated (or at least need not be complicated) and not at all mysterious. So it’s fun going through the demystification journey, and it’s fun getting to the place where you have your arms around the whole thing, and double-fun knowing that you can keep them there for good, as in this is a cinch.

* * *

And what kind of fun might it be for you?

It’s hard to say ahead of time, but the odds are good that you will find financial planning — either on your own or with a guide — to be good ol’, plain ol’ fun of some sort or another.

And not at all like going to the dentist.

About 1200 words — about a twelve-minute read max, sans linked-to content

How Hard is it to Build a Terrible Portfolio?

Monday, November 26, 2012 at 10amBy John Friedman

Over the years I’ve noticed that most people’s 401k plan portfolios tend to do about the same — they tend to pretty closely track the market as a whole, and ultimately each other, especially if given enough time.

Many of these plans tend to offer a middle-of-the-road menu of mutual funds, including some star funds, surely, but also some has-been funds and some not-so-star funds that are probably on the 401k’s menu of funds because the 401k seller made it attractive for the 401k plan buyer to choose them, all of which, in aggregate, tend to amount to a whole lot of plain vanilla, middlin’ investing.

In the past the funds in 401k plans were mostly actively managed funds, which means that the managers of the funds tried to out-perform their peers by either (a) having better absolute performance than their peers (which is the marketing-centric approach, because people love to see big numbers, don’t’ch’ya know) or by (b) having better risk-adjusted performance (which is the more financial-health-centric approach, and is less about big numbers than the market-centric approach because it’s far harder to describe and a lot less sizzley for marketing purposes) (briefly: a fund can have better risk-adjusted performance by either (1) having better performance than its peers but with equal or less risk than its peers, or (2) the same performance as its peers but with less risk than its peers).

More recently most plans also include passive index funds, which, rather than seeking to outperform their peers, instead seek to mirror the performance of a specific chunk of the worldwide stock and bond markets. Common chunks so-tracked are the overall American stock market, the overall American bond market and the all-global-stock-markets-minus-the-overall-American stock market. And there are many, many more.

So while managers of active portfolios make decisions throughout the market day and non-market hours about how to outperform the market, the managers of passive portfolios have a much narrower (though by no means simple or easy) charge: they instead seek to make sure that, at the end of the fund’s operations on each market day, the fund’s portfolio mirrors the composition of the overall market chunk the fund is seeking to mirror, and then they go on their merry way the rest of the day and have a nice evening.

* * *

All of this got me thinking about a little thought experiment. Hmmm . . .

The starting point for the thinking is the experience I mentioned above — that, once you put all these ingredients together in whatever proportions you wish, you mostly find that the portfolios tend to do about the same, and that they tend to, more or less and given enough time, fairly closely mirror the overall market.

So they congeal into a mostly-market-mirroring mix — an M-M-MM.

So how hard would it be, I wondered, to build a really badly performing portfolio out of these same basic building blocks? Clearly it’s hard to build a really wonderfully performing portfolio out of these basic building blocks — they’re too plain vanilla and too middle-of-the-road to provide much opportunity for goosing the portfolio’s performance. They gravitate towards an M-M-MM.

So . . . is it symmetrical? Could you build a really bad portfolio out of these chunks?

Could someone who has consistently proved herself/himself to be a really great fund-picker also succeed at the Building-a–Terrible-Portfolio Challenge?

So let me make this BaTPC more concrete and more basic still: if you have fifteen ordinary mutual funds with average performance and which are not very narrowly focused on a single small chunk of the market — i.e. fifteen of the sorts of mutual funds you often seen in 401k plans — can you succeed at building a gosh-awful portfolio out of those components? Can you pick losers as well as winners? And aren’t the two picking-tasks — going for excellence and going for terribleness — the same or nearly the same task?

* * *

I don’t know the answer to these questions. I am a generalist, not a money manager.

But I think a good money manager should have a lot to say about this topic, including some rocket science’y sorts of things as well as some battlefield and licking-my-wounds sorts of stories.

Any comments?

About 700 words (about a seven minute read, sans linked-to-content and sans doing much on the BaTPC thought experiment)