Google Oops

Thursday, October 18, 2012 at 1pmBy John Friedman

Now there’s something you don’t see everyday: a big public company accidentally releasing its quarterly earnings announcement before it was finalized and before the market closed, precipitating a 10% drop in the stock price and a halt of trading in its shares.

Google fall down and go boom-boom-big today on this front.

* * *

Here’s a bit of background about what all that means. Companies that have stock which average folks can buy (called publicly traded stock) are subject to extremely rigorous reporting requirements. Among those requirements are the in-due-course reporting requirements, which require the company, from the moment its shares first start trading publicly (via an initial public offering, or IPO), to release, every calendar quarter, a big, complicated announcement called a 10-Q and, once a year, an even bigger announcement called a 10–K (to remember which is which, you can think of the “Q” in “10–Q” as standing for quarterly).

And then there are also the non-due course reporting requirements, which are called 8-Ks, and which announce happenings that the public has a right to know about in near-real time (with all sorts of regulations defining what it is that the public has a right to know in near-real time). It looks like this is the type of reporting Google had trouble with today: a premature release of a draft 8-K announcing its quarterly earnings.

* * *

All of these types of announcements are exceedingly carefully written — they are scrutinized by groups of terrifically expensive lawyers and accountants and MBA-types, and they are always, always released after the market is closed (which, for us West Cost types, happens at 1 o’clock in the afternoon), so that market participants can digest the information in the release before the regular market opens the following day (yes, there is a 4-hour after-hours market that follows, too, but typically the announcement is made shortly after 1 pm West Coast time).

Today, though, in something I have no recollection of ever happening before, a big company — Google, no less, handler of info par excellence — accidentally released for all to see a draft version of its 10K, and it did so roughly four hours before the market closed.

Information just wants to run free, I guess.

* * *

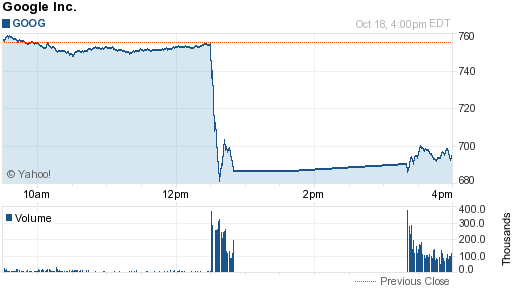

Because the release of that information was accidental and premature, the powers-that-be decided to halt trading in the stock while they figured out what to do. By then, though, the damage to the stock had already been done (one other point: the information Google released showed a softening in its core search business):

Once trading resumed, the stock recovered a smidgen but, all in all, it was about an 8% down day for GOOG.

Those vertical lines at the bottom of the graph are indications of how many shares were being traded at a given time. So when the draft announcement leaked out around 12:30 East Coast time, lots of trading happened (with some people avoiding 10% losses and some people not, kinda) and then trading was halted until a bit after 3 pm East Coast time, when there was a whole ‘nother flurry of trading activity.

To give you a point of reference, that highest vertical line shows about 400,000 shares being traded, at prices close to $700 per share. So that would be $280 million dollars worth of shares traded in just that small chunk of time (here’s how I did the zeros, which I then double-checked using Excel to make sure: 4 times 7 equals 28, and then there are seven zeros you need to bring into that 28 number, i.e. five zeros in 400,000 and two in 700, so it’s $280,000,000 — a 28 followed by 7 zeros).

And that’s just one small chunk of the day.

Yes, Wall Street plays with very, Very VERY big numbers all the live long day.

* * *

In the annals of public company-ness, this might be one of the biggest ministerial screwups ever. No, it’s not as big a screwup as the majorly blundered Facebook IPO, where various parties botched all the nuts ‘n bolts involved in coordinating the moment in time at which the actual trading of Facebook’s stock was to begin. It took almost an hour for the whole thing to get up and running, and during that time a lot of market participants were flying blind (as in, Did I just buy 100,000 shares of the stock or not?). The Facebook snafu, I suspect, will be in litigation for years, and the litigation settlements, I suspect, will be in the hundreds of millions and perhaps even top a billion dollars.

Today’s snafu was, I again suspect, much smaller in terms of dollars over which to fight. But on a different scale, this is bigger because, while Facebook’s IPO was the biggest tech IPO ever, and therefore a one-of-a-kind, what Google boo-booed today is something that thousands of companies get right all the time.

It’s a little ironic. My condolences to the folks who got hurt/will pay the price/etc. for this small act (releasing something into the info-flow of the world) with big repurcussions (time will tell).

And those who profited from it all (high frequency traders maybe?) enjoy your free money and here’s to hoping that the free-money crowd gets danced out of the markets in which they now frolic in the autumn mist.

671 words (a seven-minute read, sans links)

What Does It Mean When Big Negative Numbers Get Smaller?

Wednesday, October 17, 2012 at 12pmBy John Friedman

So, say you have a big negative number, such as, oh, I dunno, a negative 1 trillion, and say that that number measures something. And say that you measure that thing a year later and it now measures out at a negative 900 billion. Is that second number smaller or bigger than the first number?

On one hand the second number is closer to zero than the first number, which means that the second number is closer to being a positive number, which means that the second number is bigger, right?

But on the other hand the second number is smaller in its negative-ness than the other number, which means that the second number is smaller, right?

Such is the mind of a middle-schooler coming to grips with negative numbers.

Well, I am pretty sure that we’re all taught that the first explanation — the one that says that negative 900 billion is bigger than negative 1 trillion — is the correct one.

And let’s not even get started on what happens when you multiply negative numbers (no, let’s not do that . . . or should I say, yes, let’s not do that?) or fractions or, heavens to murgatroyd, the situations in which you should add exponents together or multiply them. And, no oh no, please, no fractional exponents in the mix.

* * *

I bring this up because we recently had an annual update to a series of very big negative numbers that are pretty directly impacting our lives, and because, what with all the electioning going on our there, the update didn’t make much of a splash in the media.

I speak of the federal deficit for fiscal year 2012 (which ends September 30th, right before the SCOTUS kicks into gear). The deficit for FY2012 was $1.089 trillion, down from $1.3 trillion, a decrease in the size of the deficit relative to the prior year of 16% (as always, your trusty FRED has all the federal deficit numbers going all the way back to 1901). Most would call that a step in the right direction.

Here are the numbs for the past three decades or so (my apologies to small-screen readers for the discombobulate you’ll see of this table; here is a pdf for you):

| Fiscal Year Ending On September 30th of: |

Surplus (Deficit) |

Decrease (Increase) in Deficit Over Previous Year($) |

Decrease (Increase) in Deficit Over Previous Year(%) |

President(s) During the Fiscal Year |

| 1981 | (78,968) | (5,138) | (7%) | JEC/RWR |

| 1982 | (127,977) | (49,009) | (62%) | RWR |

| 1983 | (207,802) | (79,825) | (62%) | RWR |

| 1984 | (185,367) | 22,435 | 11% | RWR |

| 1985 | (212,308) | (26,941) | (15%) | RWR |

| 1986 | (221,227) | (8,919) | (4%) | RWR |

| 1987 | (149,730) | 71,497 | 32% | RWR |

| 1988 | (155,178) | (5,448) | (4%) | RWR |

| 1989 | (152,639) | 2,539 | 2% | RWR/GHWB |

| 1990 | (221,036) | (68,397) | (45%) | GHWB |

| 1991 | (269,238) | (48,202) | (22%) | GHWB |

| 1992 | (290,321) | (21,083) | (8%) | GHWB |

| 1993 | (255,051) | 35,270 | 12% | GHWB/WJC |

| 1994 | (203,186) | 51,865 | 20% | WJC |

| 1995 | (163,952) | 39,234 | 19% | WJC |

| 1996 | (107,431) | 56,521 | 34% | WJC |

| 1997 | (21,884) | 85,547 | 80% | WJC |

| 1998 | 69,270 | 91,154 | 417% | WJC |

| 1999 | 125,610 | 56,340 | 81% | WJC |

| 2000 | 236,241 | 110,631 | 88% | WJC |

| 2001 | 128,236 | (108,005) | (46%) | WJC/GWB |

| 2002 | (157,758) | (285,994) | (223%) | GWB |

| 2003 | (377,585) | (219,827) | (139%) | GWB |

| 2004 | (412,727) | (35,142) | (9%) | GWB |

| 2005 | (318,346) | 94,381 | 23% | GWB |

| 2006 | (248,181) | 70,165 | 22% | GWB |

| 2007 | (160,701) | 87,480 | 35% | GWB |

| 2008 | (458,553) | (297,852) | (185%) | GWB |

| 2009 | (1,412,688) | (954,135) | (208%) | GWB/BHO |

| 2010 | (1,293,489) | 119,199 | 8% | BHO |

| 2011 | (1,299,595) | (6,106) | 0% | BHO |

| 2012 | (1,089,353) | 210,242 | 16% | BHO |

Now, if those double negatives and interactions don’t make your head hurt, you aren’t paying attention. Plus, if I had more time I could make it an easier set of numbers to follow.

For now I make but three points:

1. The deficit for this past year was not as big as the year before. And that is the correct direction you want to see it going in over the long-run (though many would differ about whether this is a good thing in the short-run).

2. The rest is a Rorschach Test. Choose your favorite president and see what was going on with the direction of the deficit during his (no hers in this group!) tenure. How’d the numbs do, and, either way, is he blameworthy/praiseworthy? Why?

3. As is often the case, a simple series of numbers, delta’ed and otherwise cogitated and sifted and manipulated, yields some weird results. A simple percentage calc in the table above gave two aberrant results, in instances where the negatives swung to positives and such. I haven’t the time to look into it, but I think the formula would need to be a bit more if/then oriented to truly generate smart results. As it is, I had to hardwire the results, i.e., override the simple percentage calc when it gave a couple’a negs which should’ve been positives.

Like I said, double negs and such. Ain’t the numeric universe grand . . .

681 words, and lots of numbs

(a seven minute read — but

a lotmore minutes if you

want to cozy up to

the numbs)

When HIPAAs Attack

Tuesday, October 16, 2012 at 10amBy John Friedman

As many of you know, I have been learning, up close and personal, a lot about elder issues, as my family comes together to help my father, who will be 89 in a few weeks, navigate the shoals of elder care on all sorts of levels — the financial, the medical, the legal, etc., etc., etc. There are many levels.

It’s all been very life-affirming, but by no means easy.

Dad came home last week after a bad bout of pneumonia that, when all was said and done was, believe it or not, more scary than the stroke he had this summer.

Today he’s receiving ’round the clock care. We’ll see if my folks can deal with having someone around all the time; it’s not their idea of fun. I keep telling them that, if they don’t want all that help, then I’ll be more than happy to take if off their hands. I could really use some help around here . . .

* * *

In the months ahead I’ll be writing a lot about this experience, to share with others what I’ve learned.

Today’s topic is HIPAA (pronoucned HIP’ uh), also known as the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, and a major chunk of which is about privacy and information flow.

Now I am no HIPAA expert, but I am currently the world’s greatest expert on how it has impacted my father’s access to information, and I can tell you that it has gotten in the way quite a bit.

My dad, you see, has great access to his information. Which is fine, except when he is too sick to use the information!

Making matters worse, we do not have great access to his information. True, we can log onto the website for the hospital he’s been at and see all sorts of information about him, including lab tests and whatnot. That’s all to the good.

But when it comes to his insurers — Blue Cross Blue Shield of Illinois (for Medigap coverage) and CNA (for Long Term Care coverage), mum’s mostly the word.

You could have an elderly parent on his or her deathbed, and be in great need of some information the InsCo might have, and they will tell you nothing — no, not a thing.

* * *

HIPAA release forms are supposed to solve much of the problem. These are forms which tell the company involved to provide information to certain people (e.g. spouse and children).

Similarly, we’ve used generic forms over the years to direct lots of different entities (brokerages, the VA, etc.) to (a) tell me anything I want to know, and (b) send me cc copies of everything they send to my folks.

The first part has worked just fine with every company, including the InsCos; telephone calls seem to be pretty well immune to HIPAA interference. So, now when I call one of my folks’s InsCos, they authenticate me, first using information about my folks and then information about me, and then I ask questions and get answers. That’s all well and good.

And, not to put too fine a point on it, but I am much better at interfacing with an insurance company than either of my folks. It’s in my wheel house; to them it’s a foreign country. We do believe in division of labor; it helps a lot.

* * *

It’s important to do these authorizations well ahead of when you might need the info-flow, because InsCos really don’t believe in email or pdf scans, and only infrequently (never?) will accept a fax for something of this nature. So expect the document flow process — the one that grants you entre’ into the instant info flow process — to take one to two weeks. It’s a little ironic.

Action Item Number 1, then, is for you to get yourself info-flow authorized on every important financial and medical relationship your loved ones have. And do go broad here: include in the term “loved ones” your spouse, your parents, your children, etc. — anyone who is 100% comfy with you having 100% access to the over-the-phone info-flow the company involved might push out to your loved one (and, once the authorization is in place, will push out to you).

OK?

* * *

One detail: powers of attorney can accomplish much in this context, but these HIPAA documents are specifically about information flow, exclusively, and do not provide anyone with any powers over another person’s person or property (as they say). Lots of people are OK providing others with info-flow, but providing powers of attorney is something most people do quite gingerly and usually rarely. On the flip-side, a lot of people are comfortable having the info-flow power, but not so much having the power of attorney power.

* * *

So the info-flow over the phone works OK. So what I am griping about?

The problem comes from the document-flow part — the part about getting copies of everything that’s mailed to my folks also sent to me. That part has proved highly problematic and, to date, insurmountable in some cases.

Imagine, if you will, then, that an elderly family member of yours receives a five-page long EOB — that Explanation of Benefits thing that your insurance company sends to you which, if you’re lucky, you find hard, but not impossible, to understand and, if you’re not, is totally incomprehensible. You know: it’s that computer-output’y, big-ledger’y, densely numbered thing that, if you can decipher it, shows what the InsCo paid and what it did not.

It would be nice — real nice — to get a cc copy of any EOB that goes out to my folks also sent to me at the same time. I can read these things better than they can. EOBs tend to be pretty scary and offputting.

CNA tells me, though, that the only way I can do that is to cut off my parents’ mail flow. In other words, they can send documents to only one person — no cc’s allowed — so either my folks get the document or I do, but not both of us. The reason they give for this is HIPAA. That’s also the reason they give for not being able to use email and can only use faxes when sending blank forms (and when they say blank, they really mean it).

So, HIPAA, I’m big on privacy and all, but, as CNA interprets things anyway, you are way in the way.

* * *

I add that every brokerage, mutual fund house, etc., is set up to send multiple cc copies of everything they send out to their customers; you need only direct them to do so in writing. Indeed, much of the in-house regulatory compliance brokerages et al. use is based on the house receiving cc copies of their employees’ financial account statements — all the better to see if the employees are up to no good, you see.

Not so with InsCos, leery of being in the info-shadow of HIPAA.

* * *

So my advice to all of you is that you make sure that you have a HIPAA-oriented document that tells every InsCo in each of your loved ones’ lives that you are inside, rather than outside, your loved ones’ HIPAA-zone-of-information-flow. And I do mean every loved one. If they’ll allow you in.

And if anyone knows better about how to get around the problems described here, please do get in touch or post a reply.

Thanks,

1,238 words (about a 13 minute read, give or take, and sans links)

On Shelter Comings and Goings, and Refinancings: The Certainty of Uncertainty

Monday, October 15, 2012 at 12pmBy John Friedman

One week off from writing, and I felt at a loss for a topic, until listening to Dave Ramsey on the radio this morning and then . . .

I listened to Dave answer an emailed question along the lines of, “Dave, I can re-fi my mortgage, which is at 5.125%, but I’m moving in three years. Should I do it?”

First, a quick note on language: the word “re-fi” is short for refinancing, which is the process whereby a person exchanges one mortgage lender for another. The word re-fi is usually pronounced with the accent on the first syllable and with a long I sound, as in REE’ fie, rhyming with BEE’ fly, which is what the kitty killed a couple of weeks ago — a monstrous half bee/half fly creature that was no match a’tall for the kitty’s feline apparatus.

To that question Dave’s answer was something along the lines of, “Well, you’d be going from a 5 percent to a 3 percent mortgage, and it looks like it’d be about a wash, so I wouldn’t bother.”

* * *

I disagree with most, but not all, of Dave’s answer. Here’re the yays and the nays and the whys:

1. The First Digit. In his answer, Dave focused in on the first digit of the interest rate (the “5” in “5.125”). I agree with that. Thinking about eighths of a percent (0.125% is one eight of a percent) is something you should only do when you get down to the detail of choosing a mortgage, but not when eyeballing them. And, fairly often, when you do do the detail, eighths of a percent aren’t worth thinking about at all (though they can be great for bragging rights and big-fish stories).

2. The Wash. In financial-speak, when something is a wash it means the pluses and the minuses are just about equal, so you end up in the same place because the negatives wash out the positives. Here I assume what Dave meant is that the upfront cost of doing the re-fi would just about offset the savings the caller would receive via three years’ worth of lower interest payments as a result of having a 3-something percent mortgage rather than a 5-something percent mortgage.

Whether these pluses and minuses would’ve washed has a lot to do with the size of the mortgage. The escrow-based cost of a re-fi tends to not change all that much relative to the size of the mortgage, so the bigger the mortgage being re-fi’ed, the lower would be the cost of the re-fi relative to the savings of interest.

To make this concrete, let’s assume that doing the re-fi costs $4k — which is about what they cost in California, excluding origination points, but including the appraisal, title insurance, escrow fees (escrow is a process in which an independent company holds everything, such as money, documents, etc., until the transaction is all set to happen, at which time it gives everyone the documents, money, etc. they’re getting out of the deal), and the lard-up-the-process fees that escrow companies so love to put in there, etc. In that case, Dave’s caller would need to save about $1,333.33 in interest for each of the three years, post-re-fi, that the caller planned to be in the house with the new mortgage ($1,333.33 in saved interest for each post-re-fi year, times three years of saved interest, equals the $4k escrow cost upfront) (yes, I’m ignoring the time-value of money, but these days that’s not ignoring much at all!).

On a $66,666.67 interest-only mortgage, a 2% lower interest rate would save just about that amount (I assume an interest-only mortgage to keep the math simple, which is that 2% of $66,666,67 equals $1,333.33). By the same token, on a $666,666.67 interest-only mortgage, a 2% lower interest rate would save ten times the amount, or $40,000 total over three years, which swamps — and then some — the $4,000 it cost to save that $40,000. So, the bigger the mortgage, the more reason to do the re-fi (all things being equal).

Note: $66,666.67 mortgages are rare in SF CA and Northern California in general! I use one here for illustration purposes. Also, sorry for these beastly numbs — they just worked out that way . . .

3. The tax benefit. I agree with Dave when he probably ignored the tax benefit of the mortgage deduction (briefly, if you have a big enough mortgage payment, you can deduct, for federal income tax purposes, the amount of interest you pay on your mortgage — at least for the time being, as this is one of the tax expenditures that is seemingly in play for being phased out/killed off entirely).

I say that Dave probably ignored the tax benefit because it was hard to tell what his math was all about. Nonetheless, I agree with ignoring the tax benefit for two reasons. First, the context for Dave’s answer was his radio show, which is entertainment, and the arithmetic of talking about the tax benefit would not be entertaining (I leave it to you to decide what the context here is all about).

The tax benefit math would be ugly because the better, lower interest rate mortgage would have, relatively speaking, less tax benefit (because the borrower would be paying less interest), so the gain that would come from the lower interest rate on the mortgage would also result in a loss of some tax benefit. Yes/no, plus/minus, bigger/smaller — it hurts the head just thinking about it, yes? So it doesn’t belong on radio (or, for brevity’s sake — such as it is — in this piece).

Second, as a matter of approach, I just about always ignore the tax benefit. I do this because (a) the tax benefit might go away one of these days (for mortgages on first homes, I doubt it, though I think the deduction for mortgages on second homes could be kiboshed fairly soon), and (b) people tend to not understand that it is a tax benefit tied only to real Money-Out (as opposed to being a tax benefit tied to no Money-Out) (a topic for another day), and (c) it is, in my financial planner make-it-harder-for-the-numbers-to-work conservative approach, best viewed as icing on the cake which should be enjoyed after the cake, and not while calculating whether to eat the cake in the first place (in other words, just because).

4. The Certainty of Uncertainty. But most of all, and the instigating motivation for writing this piece, is that no one knows with any kind of certainty that they will change their shelter within three years, and, in fact, my experience is that most people find that they vastly under-predict the time they will spend in their current shelter. Inertia of rest, as it happens, vastly outweighs the inertia of motion (they do not wash!).

One exception to this generality is that, when people have wee ones, they often have more apparent visibility (a parent visibility?) on when they will change shelters, based on their child’s life stage, e.g., many residents of SFCA raising young families plan on moving to the burbs when their eldest child is of school age because there’s nothing like a $30,000-plus tuition bill for your five-year old staring you in the face (which your friendly neighborhood financial planner will advise you to view as the first $45,000 of your annual income, straight off the top, since you’ll be using after-tax money to pay that tuition) to make that prediction often come to pass. But, even then, I’ve seen families change their mind once they figure out how to navigate the oh-so-burdening process of getting their kid into the right public elementary school in EssEff CA.

But think of all the people over the last five years who thought they’d be moving and have wound up staying put, for many, many reasons, most of them out of their control. Tomorrow never knows.

* * *

So if the re-fi is a wash, do bother. You just might end up staying where you are for longer than three years and you will feel like such a schmo for passing up that 3 when you could have had it and then come to find yourself, ten years later, still in the same house, still with that five and an eighth mortgage. No big-fish story for you! No bragging rights for you! How’s about, instead, a little self-deprecating humor pointed at your poor-schmo (mortgage-wise, at least) financial self?

As a bottom line, then, if you have a re-fi that will pay for itself in three years, I’d say get ye to your mortgage broker (or to the bank, but usually the broker will do better for you).

As to whether you should get a five-year fixed mortgage (because, hey, you’re only going to be in the place for three years . . .) that’s a question for a different piece (quick ‘n dirty, data- and explanation-free answer that will not fit many folks: No. Go for the 30-year fixed and do take a look at the 15-year fixed).

1269 swords (about a thirteen minute read sans links)

Anti-Science on the Science Committee

Monday, October 8, 2012 at 12pmBy John Friedman

Those who read my stuff know that I have a soft spot for numbers, and that I regret having not done more math in school.

The same is true for science, except my science education stopped at the end of my high school career rather than barely into it.

So over the years I’ve read a lot of lay-science books as well as lay-math books. There are a lot of great ones out there.

The draw for me from both of these subjects is that they both get closer to absolute truths than most other disciplines. For instance, and using a close-to-home example, when a structural engineer, using a lot of arithmetic and a lot of materials science and physics, signs off on a 2,717 foot tall building being able to stand up, essentially, forever, that’s not a guess or a belief: it’s a stone cold fact, not quite up to the exactitude of, say, 2 + 2 = 4 or the speed of light being 299,792,458 meters per second, but close enough so that folks hang out inside of the Burj Khalifa (also known as the Burj Dubai) all the time and without giving a second thought to the possibility of the building doing an all-fall-down.

So science has helped us to do a lot of amazing things by, in part, giving us the knowledge to predict what will happen over time.

* * *

I bring this up because scientists and lay-scientists, everywhere and alike, are aghast, flabbergasted and slack-jawed at a video in which Representative Paul Broun, from Georgia’s 10th District (which is east of Atlanta, bordering South Carolina and encompassing Athens and Augusta), goes 180 degrees in the opposite direction, and does so in a visual setting that you really have to see to believe:

Yes, those are, as best I can tell, a lot of dead animals, brought down, predictably, by some physics and math and human beings, and then preserved via some biology and chemistry and human beings.

* * *

Representative Broun sits, with his peer Todd Akin, on the House Committee on Science, Space, and Technology; his educational qualifications for this role are having a Doctor of Medicine degree from the Medical College of Georgia in Augusta and a B.S. in chemistry from the University of Georgia in Athens.

In the video, Broun has this to say:

All that stuff I was taught about evolution and embryology and the Big Bang Theory, all that is lies straight from the Pit of Hell. It’s lies to try to keep me and all the folks who were taught that from understanding that they need a savior. You see, there are a lot of scientific data that I’ve found out as a scientist that actually show that this is really a young Earth. I don’t believe that the Earth’s but about 9,000 years old. I believe it was created in six days as we know them. That’s what the Bible says.

Representative Broun then goes on to say that the Bible is the “manufacturers handbook”, which teaches us how to run our lives individually . . . and . . . how to run . . . everything in society.

* * *

Personally, I do not want the Bible teaching any of us how to build a tall building, thank you very much.

537 words (less than a six-minute read sans links)