The Un-Mock-Up-Able

Wednesday, August 1, 2012 at 11amBy John Friedman

Sometimes you can mock things up ahead of time — you can figure out, going into something, what it’s going to be like to be *in* that something.

And sometimes you cannot.

In JFF parlance, the former is mock-up-able and the latter is un-mock-up-able.

When something is mock-up-able, it makes a lot of sense to do the mocking up ahead of time. Indeed, one definition of wisdom is being able to predict what something will feel like/look like/etc. in the future, and, using that prediction, being able to dial in actions that will result in the unfolding of that something into a positive something. And then from that wisdom/accurate predicting/smart acting, you can find yourself, over and over again, being quite pleased with the way things are transpiring — and free from regret.

When something is un-mock-up-able, the choices are harder. Sometimes you can’t help but think about what is coming down the pike — un-mock-up-able though it may be. Your mind plays with all the possible outcomes and eventualities: what’s it going to be like when so-and-so happens? All thoughts funnel down into cogitating about it, even though those thoughts mostly generate stress and, by my definition here, don’t help you generate ideas about what you can do to increase the likelihood of a good outcome.

Other times you can ignore the upcoming so-and-so, and, then, when the time comes, you just have to put your nose to the grindstone and your shoulder into the weight and do your best in the so-and-so moment.

* * *

Illness, fading health, and plain ol’ body-much-diminished-from-what-it-once-was is, for most people, un-mock-up-able.

When it’s our own body involved, my hunch is that it’s pretty much un-mock-up-able for the vast majority of people. What would it be like if the doctor said that to me? Uhmmm, I dunno.

And when it’s a loved one’s body, why, then, we hope that all of our years of smartening up and accreting of wisdom will serve our loved one well, and our loved one’s loved ones well, because, even then, we’re all mostly in the moment.

A big heartfelt love for my father today, who is going through different parts of life’s latter journey at an increasingly rapid rate. Thanks, Dad, for everything. And when I say everything, I mean every thing.

376 words

Life’s ladder journey?

Foxes, Henhouses and SROs

Tuesday, July 31, 2012 at 12pmBy John Friedman

Very few people have ever heard the abbreviation SRO, let alone know what it stands for or means.

For those happy natives in SFCA who read, the letters mostly conjure up Single Room Occupancy, as in SRO Hotels, which are hotels that serve as residences for people without a lot of money, often in The Tenderloin or the Sixth Street area and its environs.

But for people who are licensed within The Financial Services Industrial Complex, a/k/a the FSIC (pronounced EFF’ sick), the abbreviation means only one thing: an SRO is a self-regulatory organization.

And what’s a self-regulatory organization, you might ask?

* * *

So picture this: you are in an industry that, by general consensus, is one upon which the well-being of the entire population, in part, depends. Let’s use air travel as an example.

Now picture this: the airlines, together, decide to create an association that, the airlines argue, will be best-positioned to monitor, police and, in general, regulate, the conduct of the airlines. So the head of, say, United Airlines, and the heads of the other airlines and other various components of the airline industry, get together to run the association which, in turn, regulates the industry.

Now if you’re thinking that this sounds an awful lot like the fox guarding the henhouse, you would not be alone in this opinion.

The powers that be (whomever they might be), however, very much like the idea: they think that the consequences of a failure to regulate — say, a cluster of planes falling prey to gravity and thousands of people dying — would be so powerful a disincentive that the airlines would, for-sure, behave (oh, behaaaave).

So how d’ya s’pose that would work out?

* * *

It’s hard to know how that would work out because we’ve never tried it here, and I don’t have the time to research whether any other country has tried this approach.

But I do know that, within The FSIC, the model has been alive and well for many years.

And I do know that, on October 23, 2008, about five weeks after September the 15th, no less a Biggie-Deal FSIC-fellow as Alan Greenspan had this to say in 2008, as the world around him — the financial component of which he had overseen for 20 years and had his design indelibly stamped upon it — burned:

I made a mistake in presuming that the self-interests of organizations, specifically banks and others, were such that they were best capable of protecting their own shareholders and the equity of the firms.

And also this:

Those of us who have looked to the self-interest of lending institutions to protect shareholders equity, myself in particular, are in a state of shocked disbelief.

So, at least in 2008, self-interest wasn’t working. The logical conclusion from that episode was that, when push comes to shove — or, more particularly, when avarice comes across a largely unnoticed opportunity which promises an out-sized windfall and which can also stay out-of-sight long enough to be fully reaped — SROs would not work either.

* * *

Today there is a big SRO knock-down, drag-down fight going on within The FSIC, a big-time fight, ladies and gentlemen, a big-time fight indeed. In one corner we have FINRA, which is the SRO for stock brokerages and the people within them, and which is a somewhat new entity, formed in 2007, as the regulatory sloughing off of a merger between two for-profit, shareholder-owned stock exchanges (yup, as part of the financial engineering of the 2000s, it became possible for anyone with a few dollars to own shares in some of the stock exchanges).

In the other corner we have the SEC, which currently regulates most investment advisers and the people within them, and which has been the part of the government doing this sort of work since the 1930s when we — ahem — had some problems in that particular part of our economic system and passed a lot of laws to try to make sure history did not repeat, including a law to create the SEC.

The problem, you see, is that when you look at its budget, the SEC has been drowning in a bathtub for — my guess — oh, about thirty-five years, when Alfred Kahn and Jimmy Carter launched the deregulation wave in earnest (yup, it started during Carter’s administration). And now that the SEC is near-drowned and the SRO-movement ever-more empowered, FINRA, the aforementioned SRO, has its sights set on bringing investment advisers into its own little SRO-fold.

* * *

Now, some other time I’ll discuss in here the differences between the stock brokerages and investment advisers; it’s of the essence, and it’s something that I help clients understand as The First Thing about how the investing industry is set up. Suffice for now to say that stock brokerages and investment advisers are not at all coming from the same place. Not at all. They are in many ways in opposite corners.

Law students in California in the 80s (me, for instance), learned a lot about the decades-long and apparently still-going-strong regulatory war between ophthalmologists and optometrists. Both professions work on eye health, but they have different approaches, and each, naturally, thinks their way is better. They fight for turf; they try to exclude the other. They parry and lunge at each other all the time.

Something akin to that is going on between stock brokerages and investment advisers, but, by all accounts, the old-line brokerages are losing the battle against the investment advisers. So the very idea that FINRA — regulator of stock brokerages — might end up regulating the investment advisors is, to use Greenspan’s phrase, one which leaves many investment advisors shaking their head in shocked disbelief.

Personally (and, yes, I know I am about to make a political statement here), when it comes to big, huge organizations with power, I much prefer the organization with power to be within the government rather than within the hands of large for-profit organizations. I prefer this because the former is, by definition and often in practice, by and for the people as a whole, while the latter, by definition and usually in practice, is by and for its constituents, which, when it comes to corporations, is its group of shareholders (in theory). So I see lots of instances (asbestos and tobacco to just name a few) in which for-profit corporations have been truly evil — as in intentionally causing death via very un-Golden-Rule behavior and decision-making — and not many, if any, parts of our current federal government which have shown anything even approaching the outright antipathy towards doing the right thing that those two examples highlight.

And as for competence? I think we have a draw there, in that both for-profit organizations and governments can be run well and both can be run incompetently; it just depends on who all is involved. Still, painting with a very broad brush, I view government workers as starting from a place of providing service to the community as a whole, while I see workers in for-profit organizations starting from a place of maximizing profits for the organization exclusively.

So if FINRA does indeed get the nod for regulating investment advisers, then you’ll have the fox watching the henhouse watching the worm farm — you’ll have a private enterprise (FINRA) regulating, in essence, itself (stock brokerages and the people inside of stock brokerages), and at the same time regulating the worms that the hens in the henhouse would love to eat (investment advisers and the people inside of investment advisers, a group that stock brokerages currently feel some opthamo vs optomet sort of animosity).

Howd’ya s’pose the worms would feel about that prospect?

* * *

Stay tuned here to follow the comings and goings of the FINRA vs. SEC imbroglio.

840 words when first published

1106 words final

How long can the market stay long-term flat?

Monday, July 30, 2012 at 10amBy John Friedman

Nicely ensconced atop the hubbub, sitting within the quite and privately-owned public space known as the Galleria Roof Garden, I once had a money manager say to me, we don’t have enough data.

What he meant by that is that one hundred some-odd years of data about what happens inside the American stock market is not a large enough sample from which to drawn any conclusions about how the thing, as a whole, operates.

Thank you, Martin. That we-don-t-have-enough-data idea really stuck with me.

After all, each major chunk — let’s think in terms of decades — has something totally unique about it, doesn’t it? For instance, how do you siphon out the commercialization of the Internet from the decade starting in the early- to mid-90s, so that you can draw some generalizations about it? And speaking of the WWW, how do you parse out the WWs from the ’40s and the 19-teens?

More broadly and long-term, how do you filter out the second-mover advantage the U.S. had, as our much-earlier, newly-hatched nation-self learned from (at least some of) the mistakes of other nations — avoiding hereditary monarchy, for instance — and had a nice fresh start relative to lots of other nations? And who’s to say that the advantage that we had is not fully played out at this point? I mean, look what happened to Microsoft.

* * *

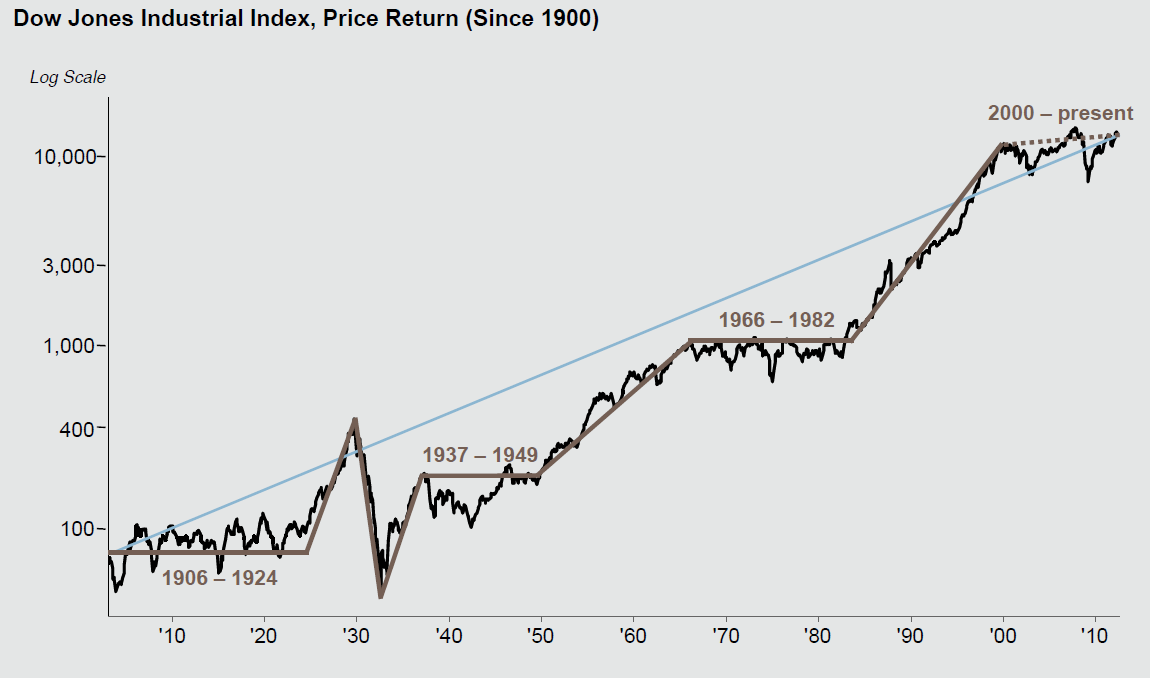

I bring this up because, by way of the inestimable Barry Rithotz, a chart caught my eye this a.m. as I searched for a topic.

- Source: as noted above,

- and JP Morgan Asset Management Guide to the Markets, Q3

- Please click on chart to gigantiate it

Plus I’ve been noodling over a question a client sent to me, which is, in essence, the title of this post: how long can the market stay long-term flat and, as a corollary, how long will fixed income investments pay negative real interest rates?

So one answer to these questions is that, if past is prologue, then, using the 1966-1982 flatlining as your yardstick, flatlining through 2016 is doable. That would mark 16 years since 2000, when the current flatlining began. And — oh no! — if you use the 1906 to 1924 flatline, then you’re talking 2018.

But is past prologue? Martin sayeth nay.

And so does The Red Queen.

And on the other hand, the last time we heard people saying “it’s a new economy” or “this time it’s different” it was not, in fact, either of those things. And I also marvel at the inertia that is the economy — how, even when it’s weak, it is incredibly resilient. Yes, there is far too much pain within its borders these days — millions of people suffering, and largely needlessly — but, yes again, the wheel, it keeps on turnin’, turnin’, turnin’, churnin’, churnin’, churnin’.

* * *

So I don’t know how long this can last. And, as I’ve been saying for years, one of the scenarios everyone should run when projecting out their numeric financial health into the future is one in which the numbers do not grow at all.

Because, so far at least, that is one scenario that you absotively, positilutely, can dial in for yourself, for real.

521 words.

Not all debt is bad debt

Friday, July 27, 2012 at 11amBy John Friedman

About a year ago in SFCA, Stephanie Miller and Thom Hartmann got booted off of AM960 Radio in the morning, to be replaced by Glenn Beck and Dave Ramsey. Sheesh, talk about a 360. The first time I heard Beck when I turned on the radio it was . . . really a harsh awakening.

Now, compared to most folks, I’m not much of a multi-tasker. When I walk down the street, I walk down the street, looking around and mostly in front of me, in the direction in which I am moving, rather than looking down, rather than looking down, at my hand, oblivious to my context.

But when I’m doing something I do everyday, such as brushing my teeth or taking a shower (one of which I even do more than once a day . . . ), I just about always listen to the radio. So I’ve gotten to know Dave Ramsey’s financial peace philosophy over the months.

I suspect I’ll have a lot to say about Dave Ramsey over the coming months and years. I find him . . . interesting, and I hope you do too. For me, doing so takes a good heaping doseful of my liberal-arts critical-thinking musk-culls . . .

So today Dave said a lot of stuff, and then went on to Neil Cavuto on Fox News, doing a simultaneous TV and radio cast, with his radio show and Fox News on cable being one-and-the-same. They talked about the price of food going up due to the drought. There were digs at government along the way.

But before that Dave said something on his radio show that got me muttering and thinking that I had my topic for today’s post. He said something along the lines of, “Rich people don’t have any debt. Just about none of ’em. That’s how they got rich.”

Dave’s backstory, you see, is that he was and is an entrepreneurial sort (look at his financial peace empire, as displayed on his website, and you’ll see what I mean — Dave loves to sell ads and loves to sell insurance leads and gosh-only-knows-what-all-else, not to mention his Financial Peace University).

As is true for a lot of entrepreneurs, when he was young Dave had a big failure (old entrepreneurs have them too; Dave had his when he was young). As he notes on his About page when telling his and his wife’s story, “Debt caused us, over the course of two and a half years of fighting it, to lose everything.” Bankruptcy ensued, with its great wiping-clean-of-the-financial slate, and then Dave did it up right and apparently super-successfully as a conservative financial radio personality, etc., etc., etc. (In fact, I’d expect that Dave’s enterprises are making tens of millions of dollars per year).

You can think of Dave as filling out the opposite end of the spectrum from Suze Orman, though his religion and politics play a far bigger role in his on-air advising and talking-headedness than Suze lets her sexuality play a role in hers.

So Dave hates hates hates debt. It hurt him badly way back when, and he has generalized that personal experience to an overall abhorrence of debt, so much so that no-debt is the central thrust, as best I can tell, of his advising.

No debt! The rest of his advice flows from that.

* * *

I have a more nuanced approach to it. I think that credit card debt — the kind that lasts month to month because it’s not paid in full each month — is bad. I hate hate hate that kind of debt, and when someone shows up in my advising world with that kind of credit card debt I view it as the financial equivalent of a guy who goes to the doctor, who right away gives the guy a stress test and then immediately — as in, Sir, you can’t even go home first — sends the poor fellow to the hospital to have quadruple bypass surgery, pronto and stet. So I view ongoing credit card debt as the pits.

And I also think that student debt, because it can virtually never be expunged via bankruptcy, is also a fairly incipient-evil sort of debt — especially if the money went to a lousy for-profit school that owes its entire existence to a badly designed student loan industry.

* * *

But after that the nuance comes in. A lot of folks in their 50s and 60s owe a good deal of their financial health to the fact that 15 and 20 years ago they were able to get a good mortgage and buy a house that wealthflowed way (WAY!) faster than the interest on the mortgage cash-gashed.

And, to go straight to the heart of what Dave said about rich people, in my experience a lot of very smart, very financially healthy people use debt in very, very productive, very, very financially healthy ways.

My word count is at 666, so I’ll leave that assertion mostly dangling for today, but I’ll add one example and a corollary to that example. Most folks, and I’ll bet Dave, too, think that Proctor & Gamble — to just pick a company that is a steady-Eddy — is a financially healthy company. Currently P&G has about $70 billion of debt versus about $135 billion of assets. So it has a roughly 2-to-1 ratio of assets-to-debt (financial wonks would typically state this as a roughly 1-to-1 debt-to-equity ratio) (ask me if you want to understand that wonkiness).

So if a rich person, had, say, $7 million of debt and $14 million of assets, then that would be about the same ratio-ballpark, right? So imagine a rich person who has built up his/her wealth through, say, a paving business. Mightn’t that business have a lot of loans inside of it? After all, it takes an awful lot of mighty big machines to pave roads. If you wait until you have the cash to buy the machines, you’ll have to do a lot of paving sans machines. And it’s a lot harder that way . . .

So, I say, with one exception, debt is neither good nor bad. Context matters. The exception is that ongoing credit card debt is bad. Period. The end. Other than that, though, it takes a bit of a conversation to say something intelligent.

And don’t even get me started on the federal government’s debt . . .

The LIBOR Olympics: Winning the Gold in the BBB Competition

Thursday, July 26, 2012 at 10amBy John Friedman

The LIBOR scandal has been brewing for a while now — five years by some measures. But it was just a month ago, on June 27, 2012, that Barclays, a British-based bank, settled with US and UK regulators to the tune of nearly half a billion dollars (“nearly” here represents a round-up of tens of millions of dollars . . . but, at scale, that is the rounded figure).

Briefly, the LIBOR scandal is the latest in a series of episodes of banks-behaving-badly, this time centering around the London InterBank Offered Rate, which is an interest rate, published each day by the British Bankers’ Association, based on objective, fact-based information various banks doing business with various banks in London submit to the BBA. As it now appears unequivocally true, some folks — Barclays folks for sure, and probably others — were gaming that rate by submitting bad information.

So rather than have an objective standard setting the interest rate, instead we had a bunch of fellows figuring out what sort of interest rate would serve their particular interests, and doing their best to make sure that that’s where LIBOR ended up that day.

The problem with that, other than the basic you’re-not-supposed-to-do-that sort of problem, is that hundreds of trillions of dollars worth of loans have their interest rates somehow pegged to the changes in the LIBOR rate, with estimates ranging from $350 trillion all the way up to $800 trillion (this latter figure being right around where the Q word, as in quadrillion, starts coming into play) (in our lifetimes, you better believe we will become conversant in using the Q word).

To put that into perspective, U.S. GDP is on the order of $15 trillion — so the LIBOR scandal touches loans worth more than 20 years’ worth of U.S. GDP — more than 20 years of the total U.S. economy. So when you mess with LIBOR, you’re messing with something totally, awesomely (in the old fashioned sense of the word), out-of-this-worldly HYUUUGE.

* * *

Now, as noted above, the L in LIBOR stands for London. And as noted in every piece of most media over the past several weeks, and in probably every part of the media starting tomorrow, the 2012 Summer Olympics are starting up in London tomorrow.

Central Casting and Aaron Sorkin could not have together cobbled together a better plotline for both the financially aware and the financially unaware out there to, once again, be hit over the head by how badly the banks have been misbehaving.

London, our eyes are upon you, in both your LIBOR’y-BBA’y’ness, and in your ability to throw the biggest sporting bash ever. Because that is, after all, what the Olympics — and especially the summer Olympics — are all about, isn’t it? Each one bigger and more grand than the last?

And this one just happens to come with a bow tied around it — a bow of BBB — Bankers Behaving Badly.

London is calling.