And you call *this* a bad Apple?!

Wednesday, July 25, 2012 at 11amBy John Friedman

Apple’s numbers are in the news today, but this time the newsworthiness is not stemming from the numbers being great, but, rather, from the numbers falling short of the fantastic sorts of numbers people have come to expect.

Personally, I still find them fantastic, in the sense of having somewhat of a fantasy quality to them. After all, what does it mean to sell $35 billion worth of stuff and bits and such in the course of 90 days? That’s about — what? — $3 billion a week or some $400 million a day. Roughly speaking.

And what does it mean to sell 26 million iPhones in the quarter? Here’s what AAPL missing its quarterly numbers looks like, at the iPhone level:

| Actual Results | |||||

|

= |

26.000 |

Millions of iPhones sold | |||

|

÷ |

7.776 |

Millions of seconds in 2012 Q2 ** | |||

|

|

|||||

|

= |

3.344 |

Actual iPhones sold per second in 2012 Q2 |

|||

|

|

|||||

| Estimates Beforehand | |||||

|

= |

29.000 |

Millions of iPhones (consensus estimate beforehand) | |||

|

÷ |

7.776 |

Millions of seconds in 2012 Q2 | |||

|

= |

3.729 |

Earlier consensus estimate of iPhones that would be sold per second in 2012 Q2 |

|||

|

|

|||||

|

|

|||||

| ** Seconds in the Quarter | |||||

|

|

|||||

|

= |

90 |

Days in 2012 Q2 | |||

|

x |

24 |

Hours per day | |||

|

x |

60 |

Minutes per hour | |||

|

x |

60 |

Seconds per minute | |||

|

|

|||||

|

= |

7,776,000 | Seconds in 2012 Q2 | |||

Yup, they sold three-and-a-third iPhones every second of every day, rather than the three-and-three-quarters folks ahead of time had expected. Those are pretty mind-blowing numbers aren’t they?

Looking at the numbers on a daily basis rather than on a second-by-second basis, the numbers are also mind-blowing, but, to me anyway, in a different way. Here the figures are that Apple sold about 289 thousand iPhones per day, while The Street was looking for it to sell roughly 322k iPhones per day. Think about the oh-the-humanity simply involved in fulfilling that task. From the person working on the machine to make the part that goes into the iPhone, all the way to the person handing the iPhone off to the user, 289 thousand times each day, weekends and holidays included.

Folks, I think about numbers a lot, and I also think about scale a lot — and the scale of numbers is one of my all-time favorite topics.

Folks, these are some mighty big numbers.

Knowin’ Komen: Being Smart About the Charities You Bring Into Your Life

Wednesday, February 8, 2012 at 4pmBy John Friedman

This piece is about how to make smart decisions when lending your support to a charity.

To get there, we’ll use as a jumping off point the story, much in the news the past ten days, of the Susan G. Komen for the Cure® charity no-go’ing, and then un-no-go’ing, its funding of some of the breast cancer screenings provided at Planned Parenthood clinics throughout the country.

It’s been a fascinating story to watch unfold, hasn’t it? And, but of course, as does most everything in our modern world, it has a clear-cut financial health aspect to it. The financial health tie-in rests upon the notion that every dollar we spend is a vote for the way we want the world to be. It follows, then, that every dollar we give to a charity is also a vote for the way we want the world to be, doesn’t it? Indeed, the given dollar is a much more wide-open, much more freely-chosen dollar leaving our control than a spent dollar (just try getting your gas and electricity from someone other than your local utility and you’ll know what I mean . . . ), and in this way the given dollar is even more of a vote, freely and voluntarily directed at those to whom we think are most deserving of it.

Given Komen’s ubiquity in the breast cancer universe, then, as well as its huge scale, you have to wonder just how many folks are now, for the first time, wondering whether, in lending their support to Komen, they had badly miscast their vote — voted, instead, for the way they didn’t want the world to be.

Hmmm . . . .

Fortunately, there are plenty of ways to smarten-up your voting. And it is to that topic that we now turn, beginning with a bit of background about Susan G. Komen and the charity named after her and built into a breast cancer powerhouse by her sister, Nancy Brinker.

* * *

Susan G. Komen: The Woman and Her Sister

The name Susan G. Komen is one that many of us had never heard before last week. And of those of us who already knew the name, many of us knew the name only because we had participated, either as a participant or as a donor, in the Susan G. Komen Race for the Cure® or bought a product with one of those pink ribbons on it.

As it turns out, Susan Goodman Komen — the woman — is a somewhat illusive figure on the web (as is true of most people who died more than thirty years ago). She does have a (necessarily) posthumous Facebook page and, with a bit of searching, you can also unearth a single picture, showing Susan, side-by-side, with her sister, Nancy Brinker (nee Goodman).

As the story is told, Nancy, a few years after Susan’s death from breast cancer in 1980, founded the charity bearing her sister Susan’s name and then grew it, from scratch, into something that has had quite an impact in a lot of fields and on a lot of different levels — an impressive feat by any measure, and notwithstanding the legs-up and apparent good fortune Nancy might have enjoyed, and regardless of how you might feel about whether those impact were positive or negative.

That single picture on the web of Susan — the picture of her with Nancy — looks to be the official picture the Susan G. Komen for the Cure® charity uses. The picture shows both women positively beaming their sisterly love for one another, with Susan’s arm around Nancy’s shoulder, and with Nancy towering over Susan.

By contrast, pictures of Nancy Brinker these days speak, to me at least, of a very different person, over and above the obvious changes that time exacts upon all of us. You be the judge.

The Susan G. Komen for the Cure® Charity: Much in the News Right Now and Not in a Happy Way

For about ten days now we have all been hearing a lot about Komen, as we watched the charity experience a corporate public-reckoning surely on a par with those experienced by McNeil (the Tylenol scare) and Coca Cola (the New Cokerollout and roll-all-the-way-back-in) way back in the 1980s, and by Netflix (the pricing and Quikster blunders) way back just a few months ago in that bygone era of 2011. And, yes, let’s also include in this public-reckoning hall of in-fame the all-too-human Tiger Woods, together with whatever corporate arms through which he markets himself.

The Fall-Out from the Reckoning: Hard Come, Easy Go.

As the dust is starting to settle, we can surmise that something like half of the people who put their lot in with Komen in the past — either via participating or donating or by going out of their way to buy a pink-ribboned product — are now wondering if, given the revelations of the past week, they made a big mistake by giving to a charity they now know has views starkly different from their own.

Why half? I’m assuming here that (a) the country is pretty evenly divided on the abortion issue around which the brouhaha revolves (with the even-steven-ness depending a lot on how the issue is framed), and that (b) people on both sides of the issue feel very strongly about it (abortion is, after all, the biggie, isn’t it, for battle lines being drawn in the American socio-political sphere?) and (c) that whatever nuance, if any, might exist in the story and its interface with the abortion issue, the feelings are strong enough on both sides that the nuance is, for all practical purposes, irrelevant. Add all that up and what you get is Komen, with the making of a single decision, setting in motion the Komen vs. Planned Parenthood dustup that angered — deeply angered — half of its support base, thereby de-loyaling about half of that base. Ouch! Three decades in the making, and three days in the half-undoing.

Terry O’Neill, the president of the National Organization for Women, goes much further: she thinks Komen will cease to existwithin five years. Time will tell . . .

The Main Topic: Being Smart About the Charities You Invite Into Your Life

So how can a person know what a charity is really up to — what it’s really like, and what it really, truly cares about? And, as a corollary, what can you do to decrease the likelihood that a charity you support over the years will one day let you down?

In addressing these questions and writing this email, I, via tight rope wire, do my best to take no political sides whatsoever — not because I have no opinion (I do, and in spite of my best efforts, I would be surprised if it didn’t show through here and there . . . ), but because the political aspects are irrelevant to the topic of how to be smart when lending your support to a charity — about how to make sure that you do not find out, years later, that you were supporting a charity that was doing something in the world that you find quite unattractive. Surely a rotten result, that.

So how do you go about being smart about this stuff?

The Two Main Online Sites that Rate Charities: CharityWatch and Charity Navigator

In yet another chapter in our recurring series called Ain’t-the-Internet-Grand, it should come as no surprise that a great place to start your smartening-up is via the dual dueling charity-ranking sites, CharityWatch and Charity Navigator (for brevity — yea right, I hear you say — and because in my experience it’s not very helpful, I leave out the Better Business Bureau site, part of which is devoted to charities).

Both CharityWatch and Charity Navigator are, themselves, charities, but, as explained below, they come across as different as night and day.

Charity Navigator: The (Self-Proclaimed) Biggest, and the More Useful of the Two Sites in Terms of Metrics

As of this writing, Charity Navigator opens its website-doors with a titlebar to its web page saying, “America’s Largest Charity Evaluator.” Now, I don’t know about you, but somehow a, “We’re the biggest” proclamation to an audience of do-gooding researchers doesn’t seem entirely appropriate, does it? It just doesn’t seem like a very charitable way to hold yourself out to the world; after all, the charity space is, more so than most, a WAITT sort of world (We’re All in this Together), rather than a YOYO sort of world (You’re on Your Own).

But maybe that’s just me . . .

Charity Navigator’s Information on Komen: Lots of Numbers to Consider

Plunging in, we find that Charity Navigator gives the Susan G. Komen for the Cure® charity four stars, which means that Charity Navigator finds the charity to be “exceptional.”

Going deeper, we see lots of normal charity sorts of metrics, e.g. an 82.5% charitable efficiency (which is the rate at which a charity’s spending budget goes towards actually doing the do-gooding that people supporting the organization want it to do), which in this case means spending $282 million doing the do-gooding, out of a total of $342 million spent overall, with the remainder going to administrative overhead ($26 million) and fundraising costs ($34 million).

The target for charitable efficiency you often hear of in this context is 85%, so Komen is doing quite well, but not top-notch, on this front.

On the other side of things, Komen brought in $320 million doing its do-gooding (think of that number this way: it’s just shy of a million bucks a day . . . ), and $38 million in letting its stored asset-base of $197 million beget other assets (for those keeping score, that is about a 20% return . . . which is nice assets-begetting-other-assets work if you can get it . . . ).

Also in there you’ll find information the media — left, right and center — highlighted this past week over and over again, showing that last year Nancy Brinker made a bit less than $500k last year running the Komen show.

I leave it to you do decide whether that is a problem or not, but I will note here that most businesses that are flowing a third of a billion dollars in and out each year usually pay their head honcho, say, ten times that much, and that, even back in the day before CEO pays gargantuan’ed, an organization of Komen’s heft would probably have paid something in the back-then-equivalent ballpark of the $500k that Brinker currently makes.

But should a charity? Hmmm . . .

CharityWatch: The Pluckiest, but Not All that Useful

By contrast, when you go to CharityWatch you’ll see a rather creaky looking website, with, I kid you not, non-clickable listings of most — but not all — of the charities it ranks. Making matters worse, when you go to its A-to-Z charity listings pageto look up a charity, what you find is a long alphabetical list of charities, most of the entries of which are non-clickable and a few of which link to a thorough analysis of a given charity — jus the sort of analysis you would like to get for all the listed charities. Frustrating!

If you go further in the CharityWatch site, you’ll see its explanation of why the good stuff isn’t online, together with pictures and articles and whatnot about its plucky head honcho whom, we can surmise, made that terrifically unfortunate keep-the-good-stuff-off-the-websitedecision. It’s easy to imagine a board meeting this past week, called to discuss the Komen controversy and its impact on CharityWatch, in which someone could be heard saying, Daniel, please, this would be the perfect time to put allour rankings online, now that Komen is so much in the news and we are getting three times the normal number of visits to the site.

But no.

In all, CharityWatch’s site makes you think that its heart is in the right place; it comes across like a feisty beatcop on the charity scene who is trying to make a difference, and who doesn’t spend much money on itself and does not put on airs. Which is how charities should be, right? And it does have a lot of useful general information on there, especially if you want to see what burrs are under the saddle of this particular charity crusader.

As a bottom line, then, if a charity you’re considering is one of the few that is analyzed in detail on CharityWatch’s site, it can be quite helpful. Otherwise, and surely in terms of specifics on given charities, not so much.

IRS 990s: For the Very rare Person Out There Who Loves Looking at IRS Forms

Online articles on how to research charities often suggest that you get your hands on the charity’s IRS Form 990.

I find that suggestion, in practice, to be 100% ludicrous and clueless. It’s kind of like suggesting that anyone who gets onto an airplane study up on the science of aerodynamics. It’s also kind of like suggesting that . . . oh I don’t know . . . that people try to understand their own 1040! Very few people understand how airplanes fly, and probably even fewer (!) their own 1040, so how on earth or elsewhere are they going to understand a charity’s 990?

Yet another reason why the media part of the financial industrial complex is out to lunch or, when not out to lunch, then out for the day and, for those times when it’s fully present, fairly often not to be trusted.

Summary of the Online Charity Rankers: A Starting Point, but Not the Finish Line.

All in all, then, these online sites are a great place to start smartening-up about a given charity. More specifically, they are particularly helpful with rule-outs. For instance, if Charity Navigator (the one with lots of information) negatively reviews a charity you’re considering, then the odds are good that the charity doesn’t have its basic nuts n’ bolts act together, e.g. it doesn’t have its financial health in order, or it is too secretive, or something else along those lines. A lot of charities are badly run . . . and you are well-advised to not give to a charity that cannot get its house in order — doctor heal thyself, and all that

But rule-outs aren’t enough, are they? I mean, giving to a charity simply because it’s not ruled out by Charity Watch/Navigator is a pretty low hurdle to clear, isn’t it? And would a simple rule-out approach have alerted people ahead of time to the coming Komen brouhaha?

The answer in unequivocally no: there is nothing on either site (and definitely not in a Form 990) that would have let you understand just what it is that makes the people running the Susan G. Komen for the Cure® charity tick.

How, then, do you get the real skinny? How do you do that?

The Harder to Find, But More Useful Information: Research the People

When Mitt Romney says, corporations are people, my friend, he is right in at least one sense — a legalistic one — because, as young law students everywhere learn, corporations have a separate legal existence and can act only through natural persons (that would be people to you and me . . . and to Mitt).

As it happens, if you had used Mr. Peabody’s Wayback Machine to research the people inside Komen before all this ruckus raised up, then you would have had a good indication about the charity’s deep-down beliefs and personality.

For instance, you would have found that George W. Bush appointed Nancy Brinker (the founder of the charity and Susan’s sister), to be ambassador to Hungary, a position she held from 2001 to 2003; you would also have found that George W. Bush later brought her on as his Chief of Protocol from 2007 to 2009.

Now, ambassadorships, in particular, tend to be really good gigs (contra: the Syrian ambassadorship these days), and both Republican and Democratic presidents have been known to reward their best bundlers — the people who bundle together contributions and raise large amounts for political campaigns — with ambassadorships.

So right there you would have had some indication about what made Nancy Brinker tick: you would know, for instance, that she probably did not vote for Al Gore or for John Kerry. And that means that, if you voted for either of those two men, then right then and there you would’ve known that someday you very well might find yourself not agreeing with Nancy Brinker’s decisions on some things.

And then there are all the board members to research, as well as all the folks shown in the “our people” or similar page for the charity, etc., etc., etc. That should give you a lot of clues.

But let’s not take guilt by association too far, OK?

More Hard to Find, But More Useful Information: Look for Mentions on the Internet by People Who Do Not Like the Charity

The Internet is full of people tirading against other people and against businesses that done done them wrong. The trick is to be able to distinguish between the tirades that spring from craziness in crazy crazed people, and those that spring from something that would probably peeve you as well.

Again using Mr. Peabody’s Wayback Machine, you could have done that sort of due diligence by performing the following online searches (with the quotes shown being part of what you actually type into the search box, signifying that you want to search for the exact phrase within the quotes):

evil charity “breast cancer”

or

“Komen sucks”

As clients can attest, I use the “______ sucks” search a lot. It’s useful because it’ll usually surface the most vociferous negative comments first; it keys you into people’s passions (some of which will be of the crazed variety, and some of which can be useful).

If you had done that way back when, then among the search results you would have found was an entryin a blog called Business for Good Not Evil. That entry would in turn have opened up a huge vein of Internet gold full of people’s thoughts about why the Susan G. Komen for the Cure® charity — separate from and prior to any issues having to do with Planned Parenthood coming up — sucked and/or was evil.

Within that vein you would have learned that a lot of people thought that Komen has inflicted major harm on the entire breast cancer eradication effort, e.g., by supporting unhealthy and perhaps cancer-causing food, by downplaying prevention and environmental concerns, by being the quintessential force behind pinkwashingand consumerist charitable efforts, by having a very split-the-baby position on stem cell research, and by being very territorial about the phrase the Cure® (I include all these circle-Rs throughout this email both (a) to emphasize Komen’s uber-territoriality, and (b) because I have a circle-R decision coming up personally, and this is my way of cozying up to the symbol and trying it on for size in some writing . . . ).

Now I am not saying that any or all of this naysaying about Komen is true; I have not done that research. But I am saying that the information was there for anyone who was thinking about supporting Komen, from which they could have drawn their own conclusions, and thereby potentially avoided errantly casting a vote for the way they did *not* want the world to be.

Local Charities: I See You

So what else might a person with an eleemosynary (a law school word, that) bent do?

To answer that question first please think of the intuitive and wise Na’vi — the people of the One Tree — in James Cameron’s Avatar, and their spoken phrase that keys into their understanding of the innate interconnectedness of all living things on Pandora: I see you.

And then please notice how, up above, we went through a lot of Internet’ing techniques to try to figure out whether some charity full of strangers was worthy of receiving our gifts — whether we felt some connectedness with the charity we could not really see.

Hmmm . . .

So maybe, just maybe, it’s a better idea to give charitably to people you can look in the eye? Or that you can at least come close to looking in the eye?

For instance, you could pop over to 1388 Sutter Street, just west of Van Ness Boulevard, a block east of the oddly-located Hotel Majestic, and there you could look into the eyes of the people who work at the Breast Cancer Fund, and focus mostly on prevention and environmental factors (as opposed to Komen’s focus on curing the disease). Maybe those neighbors are nicely in tune with what you seek to support — maybe a lot more so than the Komen folks working at 5005 LBJ Freeway, in Dallas, Texas?

As ranked by Charity Navigator, the Breast Cancer Fund is less than one one-hundredeth the size of Susan G. Komen for the Cure®, and is worthy of three stars (which is “good”), as opposed to Susan G. Komen for the Cure®’s four stars (which is “exceptional”).

And, though — drat — we can’t read the actual review of the Breast Cancer Fund at CharityWatch (Daniel!), we most assuredly can tell that CharityWatch includes the Breast Cancer Fund as one of its top rated charities, and that the list includes twelve cancer-related charities in its list (Komen not being one of them).

You be the judge. Giving is a very personal decision.

* * *

So there you have it: some ways to increase the odds that you’ll be a smart contributor to charities: (a) use one of the charity ranking sites as a starting point, and then (b) see what there is to see online about the people involved and/or whether they have any people out there singing their praises or anti-praises, and (c) always keep in mind that local enterprises might be easier to assess than those 1,800 miles away.

Dig a little, dig a lot.

That way, when you cast your vote for the way you want the world to be, you’ll increase the odds that your aim is true. You’ll increase the odds that your vote will further enable those whom you want to see succeed and, in doing so, help inch the world a bit closer to the world you want to live in, while also increasing the odds that your vote will *not* further enable those whom you wish would simply stop — stop, please stop! — doing what they’re doing because having them stop, too, would move the world in your favored direction.

Jobs’s Loss Looms Large Too

Friday, October 7, 2011 at 10amBy John Friedman

In talking to friends the last couple of days about the death of Steve Jobs, one common thread is that 12/8/80 seems to be the closest analogue because, for those of us born in the 50s, and probably for lots of others as well, Lennon and Jobs both held out the promise of a better future, and the ability of all of us to excel and change the world if only we follow our hearts and passions.

And after each of them left, the future seemed a bit less promising. All the music never to be created or heard; all the wonderful human extenders never to be designed and used.

And less good in the world. The community of humans with a bit less commonality, a bit less shared experience, a bit less yes.

The Week that Last Week Was: Choosin’ Your Zoomin’

Friday, August 19, 2011 at 10pmBy John Friedman

The Context: I initially published this piece as a group email in late mid-August of 2011. It was very much of-its-time, as the second week of August 2011 had been one of those high-volatility, big-fear, no-fun periods that happen in the financial markets from time to time (and, seemingly, from time to time happen more frequently than from time to time . . . ).

I happened to be on vacation that week, and therefore started writing a group email (now contained in this blog post) the following week, mid-week, when things had calmed down considerably but at a time when people were still very, very much smarting from the market roller coaster of the previous week.

This is what I wrote at that time.

This is a group email going out to friends and clients of JFRQ Consulting, setting out a thought-piece occasioned by the roller coaster ride the stock market took last week [i.e., the week beginning 8/8/11 — two weeks ago for folks receiving this email on 8/22/11; throughout this piece, references to “last week” are to the week beginning 8/8/11].

Those of you who know my work can well guess what I have to say about that roller coaster ride. In fact, as a useful exercise, please think about stopping your reading right here and writing down what you think about last week and, for good measure, what you think I think about last week, and then please do continue on to the thought-piece . . .

* * *

The Liberal Arts Perspective: Fractals Can Illuminate Your Experience as an Investor

We start metaphorically and liberal arts’y’y, by looking at a seemingly unrelated topic which, to one way of thinking (mine, anyway), is interestingly related to the tumult in the markets last week. Now some of you have heard me bring in the also-liberal-arts’y connection between quantum mechanics and investing, but that topic will wait for another time and another email; instead, here we look at fractals, and, more narrowly, at one branch of the fractals tree residing in the mathematics forest — topics all made popular by the book Chaos from the late 1980s, giving rise to all sorts of hard-to-look-at fractal t-shirts — and at how fractals can shed some light on what it is to be an investor in the late summer of 2011.

The Wonder of the Fractalized Perspective: How Far as it from Bolinas to Bodega Bay?

We begin with a simple question: how far is it between Bolinas and Bodega Bay? As it happens, the answer has a fractal’y, chaos’y streak running through it, and is not as clear cut as you might think.

As the car drives, the journey from Bolinas to Bodega Bay is 45.5 miles. That’s simple and fairly straightforward.

But if you click through to the link in the preceding paragraph, you’ll see a Google Map of the shortest route to take, and you’ll see that the hills and mountains of our lovely coast necessitate that a car take a question-mark-shaped route. So we can surmise that, as the crow flies, the shortest distance between Point B and point BB might be something less than 45.5 miles. So let’s call it ~35 miles (all you crow out there, please feel free to correct me . . . ).

Getting from B to BB the Long Ways Around: 250 Miles or More.

But how about if, rather than going as the crow flies or as the car drives, you decide to walk all the way along the coast (assuming it can be done and assuming that you can do it)? How long would it be then?

Walking the coastal route, to get from B to BB you would have to go all the way along the coast of the ever-beauteous, ever-magical, ever scene-of-the-consummation-of-my-betrothal-nearly-six-years-ago Point Reyes. Walking out onto Point Reyes would in turn mean walking around Drakes Bay and into and all the way around each of the four sub-bays that make up Drakes Estero, after which you would have to walk the entire south facing shore of Point Reyes. Once you completed that leg of your journey you would then need to head north and a bit east along the miraculously straight, beachy part of Point Reyes, past Abbotts Lagoon and still on, all of which is a pretty far stretch. And then, just as you came upon the most northern point of the Point Reyes Peninsula, and you were looking right at Dillon Beach and Bodega Bay, you would come to know, in a deep, more intimate way than you ever had before, that there is nothing at all like a bridge to take you there from here, and that you therefore instead had to walk back south and circle around Tomales Bay — in its entirety — which would at last get you off of the Point Reyes peninsula and back onto the coastline proper (so to speak), which can then take you fairly straightforwardly northwestward onto Bodega Bay (if you’re tide-timing is good and if you’re OK wading through the watershed just north of Miller Park.

My hunch (given the lack of roads on this route, Google Maps is of no help in this regard) is that, via this full-on coastal route, your walk from B to BB would be 250 miles or more (Drakes Estero, with all its inlets and bays, might add 50 miles to your journey all by itself).

So how long is the coast between Bolinas and Bodega Bay? Is it 45.5 miles (as the car drives), or is it 250 miles or more (as the person walks and weaves and wades and wobbles upon cliffs)?

And, while we’re at it, here’s another question for you: what if you were an ant making the coastline trek, going into every nook and cranny that’s bigger-than-an-ant’s-leap (assuming ants can leap) and therefore something which you, in your role as ant, must walk around?

Mightn’t you, as an ant, find the journey from Bolinas to Bodega Bay to be a journey of a thousand miles or more?

Hmmmm . . .

The Coastline Paradox: There are a Lot of Ways to View Wiggly Lines

This line of inquiry is called the Coastline Paradox. One popular ‘splainin’ of the Paradox looks at Britain’s coast, and notes that, if you use a hypothetical ruler roughly 60 miles long, and lay that ruler along each chunk of coast, the coastline would measure out at roughly 1,700 miles long, while if you use a hypothetical ruler that is only half that length (and therefore able to be laid upon smaller and therefore more numerous chunks of coastline), the coastline would measure out at more than 2,100 miles long.

Cool, huh?

And to really drive this point home, please have a look at this beautiful schematic depiction of the Coastline Paradox, called the Koch Snowflake, paying special attention to all three pictures on the right side of the page (ignoring, if you are like most people, the hieroglyphics on the left, and definitely grokking the two very groovy animations). Yes, folks, math can be amazing.

So the point is this: wiggly lines can look very wiggly if you look at them up close and personal, and much less so if you look at them from a vast remove.

Or, putting this in the parlance of Google Maps, GPS and other similar devices, zoom in and you see lots of wiggles and no straight lines; zoom out and you see fewer wiggles and more straight lines.

OK?

So now let’s bring this back to the stock market, shall we?

* * *

Looking at the Markets Via a Three-Month Perspective: Nothing Much Going on . . . and then Splat!

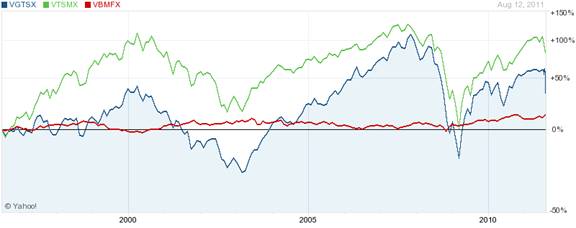

Let’s bring this back to the stock market by looking at the relative numbs from last week, in four-color pictorial representation over a three-month period ending last Friday, with the red line representing the pricing of the overall bond market, the green line representing the pricing of the overall U.S. stock market, and the blue line representing the pricing of the overall everything-but-the-U.S. stock market.

So let’s call this the three-month zoom-in:

So, yes, that is a major downdraft. And, yes again, that was a major roller coaster ride last week, with both the international and domestic stock markets (the blue and green lines) vacillating between 18% and 13% off from a month earlier, forming a fairly perfect W last week. And, yes yet again, during this period the bond market (the red line) did that steady-as-it-goes thing that it tends to do, until the stock market roiled, at which point the bond market did that come-all-ye-safety-seekers thing that it also does and, in doing so, actually increased in price.

And, yup, that price increase in the overall bond market last week means that the S&P downgrade of U.S. debt (hyperlink to primary info not possible via the S&P site) — which happened after market-close the Friday before the Monday marking the beginning of the W-week last week — utterly failed to convince bond buyers the world over that the U.S. was a less-worthy credit risk one day to the next, as, come the following Monday, people all over the globe urgently sought out those very same now-downgraded U.S. bonds. And, since things that are urgently sought after tend to become more pricey, all those bond seekers drove the prices of those bonds up up up. And, yes, that price increase meant that the interest rates those bonds pay went down down down . . . and if you don’t understand that whole bond prices up/interest rates down and vice versa relationship at a fundamental, conceptual level, then you don’t understand the first thing about bonds yet (I can, if you like, help you understand that first thing . . . just ask and we’ll make it so . . . ).

Looking at the Markets Via a Two-Year Perspective: A Lot of Up Going on . . . and then Splat! . . . but Not Enough Splat to Undo All of the Up

But now let’s zoom out a little bit, and view that same series over a two-year timeframe rather than a three-month timeframe. At this zoom level, the picture looks rather more rosy:

Now the numbers show a very big updraft, of between 20% and 35%, starting about a year ago, with most of it happening in the first six months of that period and a lot of it being undone last week, when a good chunk — but by no means all — of that appreciation went buh bye. That’s the W over there for the green and blue lines, all the way over on the right; due to the chart covering more time, though, the W is now all scrunched up, left-to-right.

Looking at the Markets Via a Fifteen-Year Perspective: A Lot of Up and Down Going on But More Up than Down

And how about if we zoom all the way out (all the way out for this type of Yahoo graph, anyway) to 15 years? Now we see this:

That would be an up-down-up-down-up sort of ride, with the up currently winning the day by quite a bit (and with domestic stocks handily whooping international stocks performance-wise — are you surprised by that?).

More descriptively, you could call that a slow and steady up followed by a slow and steady down, and then an even slower up followed by a very, very scary and very, very quick down, and then a pretty fast up, with just a hint of the drama and tragedy of last week peaking out of the chart right at the end, as last week’s W is now squished into a line that, in the grand scheme of things, is not really all that noticeable, is it?

So when using a 15-year zoom things look pretty good, but when using a three month zoom level things look horrendous. And each zoom in between tells a different, though related, story as well.

And how far did you say it was from Bolinas to Bodega?

To Every Person, Turn, Turn, Turn, There is a Zoom Level, Turn, Turn, Turn

So that’s all well and good, but let’s bring this back to your everyday life, back to you you you, and let’s do that by asking this question:

In which zoom level do you live and breathe?

Do you live in the present? In the here and now? Or are you the type who plans ahead a lot, and thinks about yourself way out into your future? Or are you like most folks, falling somewhere in between — planning for the future but also really looking forward to this weekend? Or do you live in a world of regret about the past — about paths not taken?

To Every Money-Storer, Turn, Turn, Turn, There is a Zoom Level, Turn, Turn, Turn

And more narrowly, when viewing your stored-up money, do you view it in terms of the here and now, or out in the future? Or do you think about it in the past (a lot of folks are still would’a could’a should’a’ing their tech investment portfolios circa 2000 . . . )

Or do you view your stored-up money at the zoom level of three months? That’s the first picture above, showing all’s well but then a not-at-all-ending-well flourish last week — showing the W in vivid, stomach-churning-for-most detail

Or maybe you view your stored-up money at the zoom level of two years? That’s the second picture shown above — the steady up followed by the last couple of weeks of drama — where the W is a bit less visible.

Or maybe you view your stored-up money using a fifteen year zoom? That’s the third picture above; in that picture last week’s W is not barely noticeable.

When it comes to investing, most people’s zoom level varies between not even looking to, when things get riled up, now, right now. And that means that market meltdowns like the one we had last week loom large, while market uprisings go mostly unnoticed. So for these folks last week’s market action was gut-wrenching and resolve-allaying — and still is, and the uppermost thought in their minds vis à vis the market is, should I just go to cash and be over and done with this whole dang thang?

To Every Investment, Turn, Turn, Turn, There is a Zoom Level, Turn, Turn, Turn

Now I’m all for living in the here and now (in fact, I have been known to say, mostly inaudibly, be here now, you what-a-maroon to earphone-implanted, phone-sucking pedestrians who absent-mindedly and, I think, thoughtlessly and rudely, walk into me on the narrow sidewalk-asked-to-serve-as-pedestrian-super-highway known as Montgomery Street at rush hour).

But when it comes to investing, I think it’s good to live much more in the future or, in the parlance of this email, it’s good to use a further out zoom level — one that covers more time. And taking that a step further, I’ll add that it’s also good to use different zoom levels for different chunks of money that you have stored up, each in its own vessel, each nicely designed to fulfill a specific goal of yours.

Retirement Assets: Zoom All the Way Out, and Look to Long-Term Appreciation

For instance, when it comes to retirement accounts, a lot of people’s zoom levels are best measured in decades (that is, they are twenty or more years away from retirement). And it is in the course of decades that the stock market has typically worked out very well indeed for investors. During each of those decades there were, along the way, some scary times that made everyone fearful, but those who hung in by and large made out great, as even the best-of-times/worst-of-times fifteen-year period we just lived through can attest (note for the detail-oriented: yes, if we used a 10-year timeframe, the picture is less rosy, ending up as a whole lot of carrying-on without much result — a whole lot of ruckus and hubbub, doing nothing a’tall but taking you back to whence you came, price-wise).

The moral of the story, then, for the retirement accounts of most people in, say, their 40s or younger (50s or less for some people), is that their retirement account money should be stored away in assets that are along the lines (no pun intended) of the green and blue lines in the pictures above — the sort of big-ups/big-downs-but-generally-bigger-ups-and-smaller-downs sorts of lines that domestic and international stocks tends to draw out over time.

Or, stated in the parlance of this email: for most folks retirement assets are best stored in assets that tend to look good at a twenty year zoom, zoomed all the way out.

Your Child’s Education Assets: Zoom Further and Further In as Your Child’s Age Increases (Just Like What You Do with Retirement Assets as You Near Retirement)

And how about education savings accounts, like 529 plans? Pretty much by definition most people’s zoom level for this sort of stored-up money is less than two decades, and, as time flies by and kids grow up before you even know it, their zoom levels should decrease each year, ultimately becoming less than a year.

So let’s say that Pat and Leslie, your twins, are both off to the University of Oh-My-Gosh-It-Costs-$50k-a-Year two falls from now, in which case the $100k you need for tuition is needed, for all intents and purposes, now, right now. In this now, right now context you can’t help but think about the W of last week — of the down/up/down/up that saw as much as a 15% drop in the stock market — can you? And you can’t help but think about the scary situation for you and the twins in which, just one month ago, you had your $100k of hard-earned, sorely-stored-up money set aside for the twins’s tuition, which you planned on shipping off to the University of OMGIC$50kaY in the months ahead, but which is now, after last week, $15k short of the $100k you need. Geez, you think to yourself, we could have had so much fun with that money, rather than seeing it evaporate in a week in the stock market. And now I either have to come up with another $15k or make a Sophie’s Choice about which of the twins is going to go to University of OMGIC$35kaY.

The moral of the story here is this: if you need the money anytime soon (let’s say that the “soon” here means less than ten years, though for some people “soon” should be something less than ten years), then you typically want the money to be stored in a way in which the future looks to be more like the red lines above — the steady-as-it-goes lines — the ones drawn out by the price movements of the overall bond market.

Or, stated in the parlance of the email: for most folks, money for the kids’s education is best stored in assets that tend to look good at anywhere from a ten-year zoom (when the kids are toddlers) to a two-year zoom (when the kids are teenagers) to a three-month zoom (when the kid are already off in school, and you are scrambling to put together tuition for next year).

And, yes, if you have an auto-pilot sort of 529 Plan (which most of them are, other than those managed by American Funds), this change in zoom level is built into the product itself, i.e., when you set up the account for your kid you tell the 529 plan how old your kid is and, from then on, the 529 plan changes over your stored-up money from mostly stocks to mostly bonds, in keeping with the impending need for the money. That’s the auto-pilot.

And, yes again, this sort of auto-pilot approach, taking you from mostly stock investing to mostly bond investing, is what target date mutual funds — funds with, e.g., 2020 or 2025 in their name — do for you as your near retirement, and is also something you can do on your own if you have both a mind for such things and the stick-to-it-ive’ness to actually do it on a consistent basis (some people have the former; almost everyone utterly lacks the latter).

Rainy Day Assets: Zoom All the Way In, and Look to Short-Term Cash Needs

With The Great Recession now being nearly three years old (on the ground, if not technically, leading Paul Krugman, whose predictions have been better than most, to start calling it The Lesser Depression — see the full version of that article, subject to The New York Times paywall, here) many of us have a lot of assets they view at a zoom level of now, right now.

This makes a lot of sense in our given context because lurking within most of us right now are thoughts along the lines of, I might need this money right away, so I need to keep it in cash at the bank, where I can get my hands on it on a moment’s notice, and not have to worry that the dollars I stored in there are, at the very moment I actually need them, worth something like 85 cents.

So if for you it’s been threatening rain for three years, or if for you it’s actually raining, then your rainy day money is a very important part of your financial health. Depending on your particular weather report, then, your rainy day money very well might not be well-suited to even the red line sorts of investments set out in the pictures above, and should instead be in cash cash cash. As in at the bank. As in rainy day money should be stored in cash, as in, dollars that will always be dollars.

The reason for this lies in the red lines up above. See how they have all gone up? See how the red line is up 3% in the last three months alone, so that bond prices overall have increased that much? One of these days, that up will go down.

When interest rates go up (which Ben Bernanke said very well might not happen for until mid-2013) [August 2012 update: the timeframe is now through the end of 2014] those prices will come down (there’s that rule again about bond prices and interest rates moving in opposite directions) and when that happens the dollars you put into bond investments will end up being something like 97-cent dollars of maybe even 90-cent dollars. Ouch. That would undo a lot of the good that can come from owning bonds.

So the moral of the story here is a bit more complicated: your rainy day money should be in cash or, if you can stomach some possibility of having a portion — greater or smaller depending on your particular situation — of your rainy-day-dollars becoming, say, rainy-day-three-quarters-and-a-dime-and-a-nickel, well, then maybe, just maybe, a part of your inclement weather protection should be in bonds.

Big Picture Summary: Know Your Zoom and Set Your Expectations Accordingly, and Do Think About Having Assets that Complement Each Other

So, big picture, what does this mean? It means that, if last week’s stock market gyrations had you totally freaked out (for lack of a better term) about your financial health, then you probably have unrealistic expectations about what sort of a journey you agreed to take when you invested your money. If you invested via the green or blue lines above (i.e., into domestic and international stock investments), then you should not be surprised when the market downdrafts — especially after we saw a much worse downdraft in late 2008/early 2009. In fact, you should probably be a bit happy, because the downdraft means you can buy more of what you want at a better price, which in your decades-long time frame — your twenty-plus year zoom — is apt to serve you well.

And if you went for the red sorts of lines (bond investments), then you were able to watch the carnage of last week from the sidelines. The question for you now is whether it is time to start buying some more stocks given that bonds have had a very incredible, very long-lasting appreciation (interest rates have been going down foe years and years and tears . . . ) that one of these days — we know not when — is going to go away.

And if you’re like a lot of folks and own some of both, then, please, appreciate each for what it is. Together they can create some magic which, on their own, they cannot. So please appreciate your bonds for their steadfastness and for the nice flow of income they provide to you (income flow which we have largely ignored in this email and which every picture in this email totally ignores) but also understand their shortcoming of providing little or no likelihood of increasing in value (while also marveling at their symmetrical longsuit of providing relatively little likelihood of a devastating decrease in value). And appreciate your stocks for providing a good likelihood of long-term appreciation, though with only modest income flows along the way, and with absolutely no hope of steadfastness at any zoom level at all, let alone a week when a W appears. And then keep your fingers crossed that long-term stock investing history mostly repeats itself, amen.

Wrap-Up: Pay Little or No Attention to those Money-Storing Assets Behind the Curtain, Except, Say, Quarterly or Annually

So how far is it from Bolinas to Bodega? Most people drive, and it is 45.5 miles.

And how closely should you look at your stock and bond investments? You probably cannot help but pay some attention to big moves like we are currently experiencing (yesterday, after a fairly calm first three days of the week, the market was down big again, and, to end the week, today the markets opened with a mini-W (more of a small V actually), all of which has subsided so that, as I write, the stock market has settled in at about a half of a percent down), but most people are well-advised to really cozy up to the ups and get on down with the downs of their investments no more frequently than on a quarterly basis, and to also have an annual check-in, either with yourself or with a trusted helper, aided by some long-ago-written-down promises to yourself about what sort of investor you want to be (known as an Investment Policy Statement), during which you think through whether you have the proper zoom level dialed in for the assets in your particular grouping of money-storing vessels — stocks for the long-term (decades) and bonds and cash for the medium- and short-term (years and months).

And how much should you have invested in stocks and bonds vs. invested in other money-storing assets? That is a question for a day other than today . . .

4,432 words

Lennon’s Loss Looms Large

Saturday, October 9, 2010 at 8pmBy John Friedman

Lennon’s loss, felt more strongly today because this is his 70th birthday, still haunts.

Lennon was murdered (here the dreaded passive voice is the right one to use . . . ) just about a month after Reagan defeated Carter for the presidency. What would 30 years of Lennon’s music have sounded like? What would 30 years of his life have looked like?

And what would the last thirty years of all of our lives have looked like without Reagan?

And, come to think of it, what if the marksmanships of Chapman and Hinkley had been reversed?

Hmmm . . .

* * *

Reagan’s election happened on Tuesday 11/4/80, and the murder happened on Monday 12/8/80. That Tuesday found me driving up the coast from SF to Eugene when, late at night, somewhere in the middle of nowhere on the foggy Northern California coast, by my lonesome in my little white Rabbit, I heard that Reagan had won (no surprise that, but still a dull thud of a feeling to know the fact).

Nearly five weeks later, that bad Monday found me ensconced in drippy Eugene Oregon, spending many happy hours with a delightful old Guild M20 belonging to my sweetie’s house-mate. But that evening’s very Howard-Cosell-moment found me, not enjoying the little red guitar, but, instead, having a pretty big spat with my sweetie — a spat that, when we heard the news oh boy, seemed beside the point and came to an abrupt end.

How could someone do that? How could somebody do that? To this day I can still picture her repeating these things as she cried.

The days that followed were hard. Drippy Eugene and the denoument of a long, long, loooooong relationship seemed just about right.

* * *

So maybe the waning months of 1980 marked the tide-turn — maybe they marked the time at which the figurative music died, along with all the literal music-to-be within the heart and soul and mind and ear and vocal cords of one John Winston Lennon.

Now here we are, 30 years later: Lennon is still dead but Reagan’s post-Nixon re-boot of the Repubs is quite alive, having scaled up to something that I suspect even RR himself — he who pulled in the fairly moderate Howard Baker as his chief of staff for part of his second term — would find worrisome and others right now for sure do find terrifying, as we all get used to a 10% unemployment world, with fully 14.8 million people unemployed, and 9.5 million people involuntarily underemployed (nearly 1 million of whom joined that category in the last two months alone).

Or, to put this in easier to feel, Reaganesque numbering terms: today the number of people unemployed in this lovely country of ours exceeds the number of people living in every state of the union other than the four most populous states and is just about the same as the number of people living in the 15 least populous states combined. And the number of unemployed people plus the number of involuntarily underemployed people is just about equal to the number of Texans.

* * *

Need I draw the financial health angle of this? It’s more obvious here than in most of my other posts.

If 10% of us are unable to be productive, the other 90% will suffer too. This is because the financial health of the businesses through which the 90% earn their livings will be weakened since there just aren’t enough people out there buying stuff, and whether that hits those businesses directly (because they sell stuff to consumers) or indirectly (because they don’t), it does indeed hit them. That in turn means that the financial health of the 90% earning their livings through those businesses will be weakened as well — less compensation, less opportunity, more risk of job loss, less fun in the business all around, etc.

And that means that the only folks who are unscathed, and then only relative to others, are those who are wealthy enough to be above the fray and/or lucky enough to be in an industry or a niche that is not hard hit (and there are very few of those).

So let’s say that the unscatheds amount to 1% of people out there (I suspect the percentage is actually lower). That means we have 10% unemployed, 89% employed (but less gainfully and more scarily than should be the case), and 1% who are unscathed.

As the doctor asks, So how’s that workin‘ for ya?

* * *

That, my friends, is a picture of financial ill health for one and for all. Case closed.

We are all in this together folks. We all drink at the same well. We all sup at the same table. We all sit atop the same Earth.

* * *

To close, here’s a triad of Lennon’s peace mantra, these days, as always, requiring more than a bit of imagining:

.