- POPULAR POSTS

-

- A Better Solution to Hourly Billing Practices: Radical Real-Time Hourly Fee Billing

- Living Trusts are All About Avoiding Men in Black Robes

- Shame Shame Shame on the Estate Planning Industries -- and Me Possibly Lending a Helping Hand

- Couples and Financial Planning: Of Communication Flows and Gender-Neutrality

- Towards an Industry of Pure Financial Advice

- Not all debt is bad debt

- Death and Dying, and Two Tears

- Using the California Statutory Will

- When You Get Financial Advice for Free, are You the Product?

- Tommy Lee Jones, Ameriprise and the Double-Deal

- PAST POSTS

-

- March 2020

- June 2019

- January 2017

- July 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- September 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- February 2012

- October 2011

- August 2011

- October 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- January 2010

- June 2009

- January 2009

- January 2008

- January 2007

- September 2006

- May 2006

- February 2006

- January 2006

- November 2004

- CATEGORIES

-

- The Big Picture (44)

- The Financial Services Industrial Complex (43)

- The Financial World Out There (38)

- Investing (35)

- Politics (27)

- Being Smart (23)

- Fun with Numbers (22)

- The Big Us (20)

- Elder Years (17)

- The Ways of the World (13)

- Non-Numeric Financial Health (13)

- The Wonder of It All (12)

- Retirement Planning (11)

- Taxes (11)

- Business (11)

- Financial Jargon/Financial Language (11)

- Being Human (11)

- Financial Planning (10)

- The Financial Self Within Us (10)

- Retirement Accounts (10)

- Overall Financial Health (10)

- Insurance (10)

- The Medical Services Industrial Complex (10)

- Uncategorized (9)

- Balance Sheet Design (9)

- Spending (8)

- Debt (8)

- Friedman's Law of the First Thing (8)

- Numeric Financial Health (8)

- Top 10 List (7)

- Savings (7)

- Financial Advisors (7)

- Mortgages (6)

- Estate Planning (6)

- JFF Self-Reflection (6)

- Pure Financial Advice (6)

- What's Important About Money (5)

- Real Estate (5)

- Privacy (5)

- Building Your Financial Brain Trust (4)

- JF Self-Reflection (3)

- Online Safety (3)

- Technology (3)

- Making a Living (3)

- Scale Tales (3)

- Working for a Living (3)

- Lifestyle Decision-Making (3)

- MBAisms (3)

- Education Accounts (3)

- Money-Stored (2)

- Fun (2)

- Your Financial Personality (2)

- Financial Writing (2)

- Cashflowing (2)

- Money-In/Money-Out (2)

- Interest Rates (1)

- The Insurance Services Industrial Complex (1)

- The Legal Services Industrial Complex (1)

- Healthcare (1)

- Business of Financial Planning (1)

- Heathcare (1)

- Financial Ops (1)

- Friedman's Law of the 1st Thing (1)

- Children (1)

- Time Off from Blogging (1)

- Financial Wonkery (1)

- Couples (1)

- TAGS

-

- AUM fees (13)

- Microsoft (10)

- Dave Ramsey (10)

- Apple (9)

- Facebook (9)

- Rorschach Test (9)

- Paul Krugman (9)

- NFs (9)

- Normal Folks (9)

- George W. Bush (8)

- Mitt Romney (8)

- FSIC (7)

- WAITT (7)

- MSFT (6)

- FRED (6)

- Google (6)

- E*Trade (5)

- Excel (5)

- luck (5)

- iPhone (5)

- Ronald Reagan (5)

- IPO (5)

- Twitter (5)

- Medicare (5)

- YOYO (5)

- SFCA (5)

- Wall Street (5)

- The Fiscal Cliff (5)

- Vanguard (5)

- Ess Eff Sea Eh (5)

- Social Security (5)

- BofA (5)

- Wells (5)

- Citi (5)

- Chase (5)

- Paul McCartney (5)

- vig (5)

- death (4)

- Steve Jobs (4)

- AAPL (4)

- SCOTUS (4)

- macroeconomics (4)

- Schwab (4)

- GDP (4)

- eBay (4)

- Alan Greenspan (4)

- family (4)

- ObamaCare (4)

- George Harrison (4)

- Bill Clinton (4)

- Barack Obama (4)

- life insurance (4)

- index funds (4)

- 401k plans (4)

- John Lennon (3)

- money-in (3)

- GE (3)

- Komen (3)

- phishing (3)

- money-out (3)

- predictions (3)

- Osama bin Laden (3)

- The New Yorker (3)

- basis points (3)

- SEC (3)

- FB (3)

- Dems (3)

- Repubs (3)

- Paul Ryan (3)

- Yahoo Finance (3)

- Lehman (3)

- Groupon (3)

- mutual funds (3)

- Nate Silver (3)

- Noe Valley (3)

- Zynga (3)

- EOB (3)

- The Beatles (3)

- dentists (3)

- Medicaid (3)

- FSPs (3)

- FWoJT (3)

- Kafkaesque (3)

- commissions (3)

- TANSTAAFL (3)

- Warren Zevon (3)

- California (3)

- lawyers (3)

- Michael Kitces (3)

- BPs (3)

- Fandango (2)

- investing (2)

- BP (2)

- hockey players (2)

- General Electric (2)

- big numbers (2)

- righteous death (2)

- entropy (2)

- HP12C (2)

- PMT (2)

- savings rate (2)

- credit cards (2)

- dementors (2)

- Harry Potter (2)

- inflation (2)

- Krugman (2)

- lefties (2)

- righties (2)

- Ritholtz (2)

- The Big Us (2)

- VTI (2)

- scam (2)

- money-stored (2)

- NINY (2)

- gold (2)

- guns (2)

- writing long (2)

- bankruptcy (2)

- nuance (2)

- Proctor & Gamble (2)

- Interest rates (2)

- financial-speak (2)

- COBRA (2)

- Barry Ritholtz (2)

- The Red Queen (2)

- Vice Versa Rule (2)

- Al Pacino (2)

- PPACA (2)

- Netflix (2)

- James Bond (2)

- Mr. Softee (2)

- Todd Akin (2)

- austerity (2)

- AIG (2)

- Bank of America (2)

- Powers that Be (2)

- Game Theory (2)

- Blackberry (2)

- Bain Capital (2)

- Bad Astronomy (2)

- LinkedIn (2)

- New York Times (2)

- Mia Bella (2)

- Eric Idle (2)

- Iraq (2)

- urban infill (2)

- Market Street (2)

- income tax (2)

- dividends (2)

- capital gains (2)

- science (2)

- math (2)

- Ess Eff CA (2)

- HIPAA (2)

- Ironic (2)

- Sgt. Peppers (2)

- money managers (2)

- auto-ding (2)

- IAPD (2)

- George Lakoff (2)

- Frank Lutz (2)

- Dan Hicks (2)

- POTS (2)

- voting (2)

- Bush v. Gore (2)

- Procol Harum (2)

- Grover Norquist (2)

- Cass Sunstein (2)

- The Left (2)

- UHNWs (2)

- HNWs (2)

- Ameriprise (2)

- Fidelity (2)

- Michael Pollan (2)

- human nature (2)

- Talking Heads (2)

- MoneyChimp (2)

- eyeballability (2)

- eyeballable (2)

- Phil Plait (2)

- asset-gathering (2)

- active investing (2)

- Abraham Lincoln (2)

- fun (2)

- FPers (2)

- Meg Whitman (2)

- James Baker III (2)

- Bette Midler (2)

- Chicago (2)

- BLBHBs (2)

- Roth accounts (2)

- CAGR (2)

- IRS (2)

- PITB (2)

- simplicity (2)

- TDAs (2)

- TPAs (2)

- IRAs (2)

- 403b plans (2)

- HSAs (2)

- Ringo Starr (2)

- Johnny Cash (2)

- CPAs (2)

- Congress (2)

- free lunch (2)

- Baby Boomers (2)

- Clint Eastwood (2)

- monthly nut (2)

- oh the humanity (2)

- Monty Python (2)

- Federal Reserve (2)

- George Costanza (2)

- Top 10 List (2)

- who gets what (2)

- David Letterman (2)

- Malcolm Gladwell (2)

- Star Trek (2)

- yay (2)

- Goldilocksian (2)

- doctors (2)

- Dire Straits (2)

- Seinfeld (2)

- Soup Nazi (2)

- Quicken (2)

- pricing (2)

- Ess Eff Sea Ay (2)

- estate planning (2)

- estate tax (2)

- revenue models (2)

- Mosaic 1.0 (2)

- Internet Bubble (2)

- standard of care (2)

- respite (2)

- hospice (2)

- love (2)

- San Francisco (2)

- leverage (2)

- Mid-Market (2)

- Rule of 72 (2)

- Silicon Valley (2)

- InsCo (2)

- rules of thumb (2)

- DOL (2)

- exceptionalism (2)

- ISIC (2)

- MSIC (2)

- AARP (2)

- cause of death (2)

- dying (2)

- Howard Baker (1)

- maximization (1)

- honesty (1)

- got’ch’ya (1)

- RVW’ed money (1)

- RVW (1)

- Rip Van Winkle (1)

- banks (1)

- asset gatherers (1)

- index investing (1)

- Hindenburg (1)

- homebuyers (1)

- fish (1)

- domain (1)

- 529 accounts (1)

- TUFFF (1)

- portfolio (1)

- investments (1)

- Heisenberg (1)

- Einstein (1)

- Marx (1)

- lefty (1)

- dialectic (1)

- 9/11 (1)

- blogging (1)

- sinkhole (1)

- LIBOR (1)

- quadrillion (1)

- Aaron Sorkin (1)

- Central Casting (1)

- Olympics (1)

- Malcom Gladwell (1)

- rent vs. own (1)

- charity (1)

- giving (1)

- the cut-off (1)

- mortgage brokers (1)

- mortgages (1)

- NPV (1)

- PV (1)

- security (1)

- craigslist (1)

- unemployed (1)

- underemployed (1)

- Bill Janklow (1)

- devil numbers (1)

- South Dakota (1)

- usury (1)

- Walter Wriston (1)

- ZTABS (1)

- aggregate demand (1)

- empathy (1)

- Kedrosky (1)

- unemployment (1)

- fungible (1)

- magical dollars (1)

- simplification (1)

- scammers (1)

- vigilance (1)

- Webloyalty (1)

- fee income (1)

- George Bailey (1)

- spread income (1)

- probabilities (1)

- probabilty cloud (1)

- portfolio design (1)

- SFO (1)

- NFP (1)

- righty (1)

- wordcount (1)

- General Motors (1)

- GM (1)

- growth stocks (1)

- value stocks (1)

- Goldman (1)

- Louis Rukeyser (1)

- forecasts (1)

- survivalism (1)

- loyalty (1)

- Donald Trump (1)

- alignment (1)

- transparency (1)

- United Airlines (1)

- LUV (1)

- UAL (1)

- Kafka (1)

- Catch-22 (1)

- Suze Orman (1)

- student loans (1)

- credit card debt (1)

- multi-tasking (1)

- entrepreneurs (1)

- P&G (1)

- NPR (1)

- architecture (1)

- al Qaeda (1)

- annuities (1)

- fiduciaries (1)

- TravelZoo (1)

- portability (1)

- POPS (1)

- RQ (1)

- Inside Baseball (1)

- FINRA (1)

- SRO (1)

- opthomology (1)

- optometry (1)

- brokerages (1)

- Alfred Kahn (1)

- SkyNet (1)

- mock-up-able (1)

- un-mock-up-able (1)

- wisdom (1)

- physical health (1)

- aging (1)

- life's journey (1)

- Kinight Capital (1)

- big things (1)

- Zuckerberg (1)

- fail (1)

- BLS (1)

- Meteor Blades (1)

- job creation (1)

- U3 (1)

- politics (1)

- QnDGA Series (1)

- cashflow pump (1)

- Ezra Klein (1)

- Sarah Kliff (1)

- $716 Billion (1)

- 60 Minutes (1)

- WonkBlog (1)

- CBO (1)

- ACA (1)

- Nancy Brinker (1)

- New Coke (1)

- Tylenol (1)

- Tiger Woods (1)

- pink ribbons (1)

- CharityWatch (1)

- eleemosynary (1)

- I See You (1)

- Na'vi (1)

- Avatar (1)

- Pandora (1)

- Mr. Peabody (1)

- Wayback Machine (1)

- MUNI (1)

- John Schnatter (1)

- healthcare (1)

- EssEffSeeEh (1)

- Neil Cavuto (1)

- 10-to-1 (1)

- tautology (1)

- The JFF Blog (1)

- iPod (1)

- Forbes (1)

- Kurt Eichenwald (1)

- Vanity Fair (1)

- Charlie Rose (1)

- revenues (1)

- revs (1)

- Timothy Worstall (1)

- Netscape (1)

- mafia (1)

- Henry Blodget (1)

- EPI (1)

- OECD (1)

- Lawrence Kudlow (1)

- FSMC (1)

- Chile (1)

- Mexico (1)

- Turkey (1)

- U.S.A. (1)

- iOS (1)

- Ramussen (1)

- the NAZ (1)

- Grace SLick (1)

- Matt Ridley (1)

- Texas Hold 'Em (1)

- JFRQ Consulting (1)

- spoonerism (1)

- Archie Bunker (1)

- IPS (1)

- fractals (1)

- chaos theory (1)

- Bolinas (1)

- Bodega (1)

- Drake''e Estero (1)

- Point Reyes (1)

- Abbots Lagoon (1)

- Drakes Bay (1)

- Google maps (1)

- S&P downgrade (1)

- zoom level (1)

- Recession (1)

- JFRQ group email (1)

- US Airways (1)

- Firefox (1)

- Merrill (1)

- Reserve Fund (1)

- repos (1)

- commercial paper (1)

- Fannie Mae (1)

- Freddie Mac (1)

- P2B (1)

- Annie Lowrey (1)

- OWS (1)

- The 99% (1)

- The 1% (1)

- The 47% (1)

- % (1)

- Peggy Noonan (1)

- Jack Welch (1)

- repeat play (1)

- single play (1)

- financiers (1)

- business people (1)

- hover function (1)

- iWhatever (1)

- iPad (1)

- iTouch (1)

- Thunderbird (1)

- Mail (1)

- I Want My HDTV (1)

- HDTV (1)

- I Want My MTV (1)

- collectivism (1)

- Bad Astronoer (1)

- Phill Plait (1)

- Mars (1)

- the Moon (1)

- Bas Lansdorp (1)

- Alice Kramden (1)

- scarcity (1)

- Stop It! (1)

- ROI (1)

- Elon Musk (1)

- market cap (1)

- Intel (1)

- Trulia (1)

- LNKD (1)

- ETFs (1)

- RAND (1)

- Ralph Fielding (1)

- Votamatic (1)

- Intrade (1)

- Ireland (1)

- Billy Bean (1)

- Grinnell College (1)

- Psych 101 (1)

- Wile E. Coyote (1)

- Dick Cheney (1)

- Liz Cheney (1)

- Ron Suskind (1)

- prism glasses (1)

- happiness (1)

- Daniel Gilbert (1)

- David Cameron (1)

- Iraq are (1)

- Jax (1)

- Peg Bundy (1)

- Sons of Anarchy (1)

- SOA (1)

- Midwest trees (1)

- SFMOMA (1)

- Bay Bridge (1)

- Genentch (1)

- Dumbarton Bridge (1)

- PayPal (1)

- Loma Prieta (1)

- Nat King Cole (1)

- Impact Investing (1)

- II (1)

- Ida James (1)

- SRI (1)

- Kiva (1)

- micro-lending (1)

- Big Philanth (1)

- nineteen for me (1)

- Taxman (1)

- Tax Foundation (1)

- interest (1)

- Wesley Snipes (1)

- John Branca (1)

- Esalen Institute (1)

- Pacific Grove CA (1)

- Carmel CA (1)

- fun-ster (1)

- The Tenderloin (1)

- Lovers Point (1)

- Lighthouse Ave. (1)

- Big Sur (1)

- Tom Rush (1)

- Driving Wheel (1)

- Paul Broun (1)

- Burj Khalifa (1)

- Burj Dubai (1)

- speed of light (1)

- biology (1)

- chemistry (1)

- Donna Summer (1)

- On the Radio (1)

- mortgage (1)

- refi (1)

- wash (1)

- escrow (1)

- title insurance (1)

- bragging rights (1)

- big-fish stories (1)

- escrow fees (1)

- tax expenditures (1)

- mortgage broker (1)

- eyeballing (1)

- CNA (1)

- federal deficit (1)

- negative numbers (1)

- fractions (1)

- exponents (1)

- Murgatroyd (1)

- GOOG (1)

- HFT (1)

- 10K (1)

- 10Q (1)

- doing the zeros (1)

- Black Friday (1)

- Flash Crash (1)

- MMs (1)

- Brochure (1)

- The Item Fives (1)

- infaation (1)

- Into the Wild (1)

- x-bike (1)

- PnP (1)

- EssEff CA (1)

- stock brokers (1)

- Fox Business (1)

- Republicans (1)

- Democrats (1)

- Jim Carville (1)

- GHW Bush (1)

- Larry Doyle (1)

- Matt Egan (1)

- voting lines (1)

- NSPOTS (1)

- NSPOTSWIT! (1)

- Three 9s (1)

- embarrassment (1)

- iTubes (1)

- Ted Stevens (1)

- tubes (1)

- mobile phones (1)

- big machines (1)

- sunflower (1)

- Fibonacci (1)

- Christine Romer (1)

- tax rates (1)

- NBush v. Gore (1)

- John Kerry (1)

- Wile'y Coyote (1)

- Roadrunner (1)

- 1031 exchanges (1)

- bonds (1)

- tax-ugly (1)

- tax-beautiful (1)

- tax-deferred (1)

- Treasurys (1)

- sausage-making (1)

- CGs (1)

- ASAP (1)

- Halloween (1)

- Thanksgiving (1)

- 1040-tweaking (1)

- Gary Brooker (1)

- Proposition 13 (1)

- defense spending (1)

- nudges (1)

- Richard Thaler (1)

- The Right (1)

- The New Deal (1)

- Mother Jones (1)

- The Aughts (1)

- The Teens (1)

- Naughty Aughties (1)

- Proposition 30 (1)

- Robert Reich (1)

- the s-c s-c FC (1)

- generic advice (1)

- Uranium 235 (1)

- Uranium 238 (1)

- Tommy Lee Jones (1)

- Batman (1)

- High Net Worth (1)

- Steven Segal (1)

- Kate Blanchett (1)

- Missing (1)

- fiduciary duties (1)

- fiduciary (1)

- double-dealing (1)

- Under Siege (1)

- UHS (1)

- crevice (1)

- crevasse (1)

- Hostess (1)

- Twinkies (1)

- Hostess Cupcakes (1)

- Motorola (1)

- Jim Collins (1)

- Built to Last (1)

- RIM (1)

- dodo bird (1)

- Nutraceutical (1)

- Real Foods (1)

- David Byrne (1)

- Ding Dongs (1)

- Ho Hos (1)

- Pisces Fish (1)

- microeconomics (1)

- the GPs that B (1)

- Macro 101 (1)

- Micro 101 (1)

- wheat (1)

- chaff (1)

- liberal (1)

- Krugman on Feist (1)

- Why Y? (1)

- The Ps that B (1)

- Bill Gross (1)

- John Paulson (1)

- Allen West (1)

- Pink (1)

- No Doubt (1)

- Justin Bieber (1)

- Marco Rubio (1)

- Psy (1)

- sleeping well (1)

- Jen Wasson (1)

- Otis (1)

- financial coach (1)

- Example 7 (1)

- Wasson Design (1)

- FHA (1)

- pure advice (1)

- music (1)

- Ess Eff See A (1)

- Sula (1)

- my folks (1)

- vibrating air (1)

- gravity (1)

- geology (1)

- AMAs (1)

- MTBs (1)

- Rocket Science (1)

- BaTPC (1)

- Lincoln (1)

- M-M-MM (1)

- dentist jokes (1)

- feoffing (1)

- washing your car (1)

- slack-cutting (1)

- forgiveness (1)

- thankfulness (1)

- Michael Parks (1)

- human beings (1)

- it's a cinch (1)

- HPQ (1)

- DELL (1)

- HP (1)

- Hewlett Packard (1)

- Michael Dell (1)

- hockey stick (1)

- Autonomy (1)

- Compaq (1)

- skill (1)

- luck vs. skill (1)

- Sam Alito (1)

- Al Gore (1)

- Andy Card (1)

- Desert Rose (1)

- Bob Edwards (1)

- architects (1)

- Mohamed Atta (1)

- Taliban (1)

- Tora Bora (1)

- Afghanistan (1)

- Waziristan (1)

- Middle East (1)

- Lebanon (1)

- Iran (1)

- Hezbollah (1)

- WTC (1)

- cram-down (1)

- Stanley Kubrick (1)

- war (1)

- Bob Costas (1)

- gun control (1)

- Ted Nugent (1)

- Jovan Belcher (1)

- RCP (1)

- suicide barrier (1)

- Beach Boys (1)

- summer fun (1)

- chicken jokes (1)

- Jason Whitlock (1)

- Kansas City (1)

- Dog-Eat-Dog (1)

- life's last (1)

- Top Dog (1)

- easily deadly (1)

- YOYODED (1)

- Laura Clawson (1)

- Daily Kos (1)

- Rod Stewart (1)

- B2B (1)

- capital vs labor (1)

- labor vs capital (1)

- pix (1)

- Robert Brusca (1)

- CNN (1)

- CNNMoney (1)

- Chris Isidore (1)

- Wizard of Oz (1)

- Tin Man (1)

- Ted Waitt (1)

- Gateway (1)

- Jerry Brown (1)

- Keystone-Cop’y (1)

- Messrs. H and P (1)

- David Packard (1)

- Bill Hewlett (1)

- Mrs. Robinson (1)

- Morgan Housel (1)

- Motley Fool (1)

- instant grat (1)

- Washington D.C. (1)

- people-kind (1)

- values-added-in (1)

- 1040 (1)

- ink-blots (1)

- National Mall (1)

- White House (1)

- Bigfoot (1)

- Sasquatch (1)

- RAC world. (1)

- Roman Polanski (1)

- Macbeth (1)

- Out Damn Spot (1)

- financial models (1)

- SOL (1)

- Ps2B (1)

- 30-somethings (1)

- RAC (1)

- Ps-that-B (1)

- heal thyself (1)

- Tip O'Neill (1)

- for Pete's sake (1)

- Apple's cash (1)

- Lionel Richie (1)

- All Night Long (1)

- lock-in (1)

- mommy-van (1)

- Big Four Banks (1)

- credit unions (1)

- MBA-brain (1)

- Mom and Pop (1)

- Eric Clapton (1)

- 12/12/12 Concert (1)

- ESPP accounts (1)

- vessels (1)

- TTAs (1)

- OIGs (1)

- M. Scott Peck (1)

- Herman Cain (1)

- shucky ducky (1)

- Uncle Sam (1)

- tax-code-ese (1)

- carried interest (1)

- tax-rate-risk (1)

- Fab (1)

- When We Was Fab (1)

- Jeff Beck (1)

- amortizing (1)

- spread (1)

- 30-year mortgage (1)

- fully-amortizing (1)

- Paul Rogers (1)

- reactive death (1)

- proactive death (1)

- onco death (1)

- The Godfather (1)

- Sting (1)

- Roberta Flack (1)

- In My Life (1)

- Trent Raznor (1)

- Hurt (1)

- Nine Inch Nails (1)

- Rick Rubin (1)

- I Hung My Head (1)

- Sandy Hook (1)

- gallows (1)

- head-hanging (1)

- LLC (1)

- Ari Fleischer (1)

- R&D tax credit (1)

- Portland Oregon (1)

- Muni bonds (1)

- tax-goading (1)

- filibusters (1)

- ATRA (1)

- James Stewart (1)

- Frank Capra (1)

- Byrd Rule (1)

- EGTRRA (1)

- Tax Relief (1)

- 9/11/01 (1)

- TRUIRJCA (1)

- Gerard Depardieu (1)

- France (1)

- Russia (1)

- da mo' da betta' (1)

- Beatles (1)

- boundary event (1)

- Cleaver Family (1)

- Friedman Family (1)

- DNA (1)

- family stuff (1)

- eleventy (1)

- twelvety (1)

- J.R.R. Tolkien (1)

- The Who (1)

- long life (1)

- despising-lobby (1)

- RMDs (1)

- MRDs (1)

- FinancialWonks (1)

- F-Wonks (1)

- fwonks (1)

- TTDAs (1)

- RMDs vs. MRDs (1)

- MRDs vs. RMDs (1)

- the hard way (1)

- J.K. Rowling (1)

- leap days (1)

- scalars (1)

- SBUX (1)

- Starbucks (1)

- Lee Eisenberg (1)

- The Number (1)

- nest egg (1)

- Atrios (1)

- USA Today (1)

- Duncan Black (1)

- Eschaton (1)

- DB vs. DC (1)

- DC vs. DB (1)

- Oldsmobile (1)

- private accounts (1)

- DCs (1)

- DBs (1)

- chained CPI (1)

- Bernie Sanders (1)

- B-2-C dosey doe (1)

- lickety-split (1)

- portmanteau (1)

- Carole King (1)

- Eddie Haskell (1)

- June Cleaver (1)

- TBTF Banks (1)

- 2B2F (1)

- Citibank (1)

- Wells Fargo (1)

- BCCW Cartel (1)

- Fargo (1)

- Coen Brothers (1)

- Marge Gunderson (1)

- money supply (1)

- M1 (1)

- M2 (1)

- ya bet'ch'ya (1)

- you bet'ch'ya (1)

- price fixing (1)

- signaling (1)

- The Atlantic (1)

- Franz Kafka (1)

- rant (1)

- PITB expense (1)

- Kaiser (1)

- pooling risk (1)

- murder mysteries (1)

- high deductibles (1)

- Rip Van Winkling (1)

- asset gathers (1)

- Brylcreem (1)

- careful boss (1)

- precommitment (1)

- spending's reach (1)

- Suzy Khimm (1)

- Sequester (the) (1)

- Scott Galupo (1)

- Larry Kudlow (1)

- CNBC (1)

- Forbes magazine (1)

- yada yada yada (1)

- GHP (1)

- On and On (1)

- Stephen Bishop (1)

- CNBC.com (1)

- crowding out (1)

- The Economist (1)

- pension plans (1)

- take a powder (1)

- Roth conversions (1)

- shine it on (1)

- brain trust (1)

- roll-overs (1)

- mindfulness (1)

- bar dice (1)

- MindfulFinancial (1)

- making a living (1)

- brain trust'ees (1)

- do right by (1)

- Wiktionary (1)

- Bing Crosby (1)

- Romper Room (1)

- The Secret (1)

- Stanley Tucci (1)

- texting (1)

- Paul Bettany (1)

- Bob Marley (1)

- OIALTO (1)

- Oy ALto (1)

- Golden Rule (1)

- Charles Dickens (1)

- remodels (1)

- pets (1)

- dogs (1)

- veterinarian (1)

- BMW (1)

- Mercedes (1)

- CPA'y (1)

- spendthrift (1)

- sanguine (1)

- peruse (1)

- pets (cost of) (1)

- thrift shops (1)

- Steve Wonder (1)

- Elvis Presley (1)

- Mandy Patinkin (1)

- cats (1)

- cash-suck (1)

- kids (cost of) (1)

- San Rancisco (1)

- used car values (1)

- Kelley Blue Book (1)

- tax basis (1)

- rainy days (1)

- meta-don't (1)

- Seth MacFarlane (1)

- David Crosby (1)

- Fox News (1)

- Ben Affleck (1)

- marriage is work (1)

- Left Coast (1)

- Right Coast (1)

- gender politics (1)

- Ernest Hemingway (1)

- Tom Robbins (1)

- quiet rooms (1)

- Phoenix Books (1)

- Scarface (1)

- Compliance (1)

- Ayn Rand (1)

- Harold Robbins (1)

- Danielle Steel (1)

- Edward Tufte (1)

- PowerPoint (1)

- big cheese (the) (1)

- Cannes (1)

- WAG numbers (1)

- .xls (1)

- Form ADV-II (1)

- turnip blood (1)

- not equal to (1)

- greater than (1)

- less than (1)

- Hartford CT (1)

- Star Wars (1)

- mind-trick (1)

- mind-meld (1)

- economic rents (1)

- The Golden Rule (1)

- hippies (1)

- magic 7s (1)

- Jimmy McMillan (1)

- CCCs (1)

- hippie days (1)

- magic tricks (1)

- magicians (1)

- killing the 7s (1)

- Christpher Nolan (1)

- Batman Begins (1)

- The Dark Knight (1)

- Gran Torino (1)

- get off my lawn (1)

- no problem (1)

- you're welcome (1)

- thank YOU (1)

- customer service (1)

- CRM (1)

- Sacramento (1)

- Rancho Santa Fe (1)

- Pleistocene Era (1)

- VOIP (1)

- EFP (1)

- datadump (1)

- bifurc (1)

- garbage dumps (1)

- Ps that Be (1)

- batphone (1)

- Polycom (1)

- permutations (1)

- iterations (1)

- combinations (1)

- Lake Cook Road (1)

- Skokie Highway (1)

- Scott (1)

- Doug (1)

- Marty (1)

- snow fight (1)

- The Pretenders (1)

- Chrissie Hynde (1)

- My City was Gone (1)

- macro class (1)

- Andrew Rose (1)

- Greg Mankiw (1)

- MBA-types (1)

- DIY EPers (1)

- Dixie Chicks (1)

- Hoyt Axton (1)

- No No Song (the) (1)

- know-it-all (1)

- Cliff Clavin (1)

- Cheers (TV show) (1)

- zero lower bound (1)

- Ivan Pavlov (1)

- B.F. Skinner (1)

- signal and noise (1)

- signal (1)

- noise (1)

- noise and signal (1)

- Bat Chain Puller (1)

- French TV (1)

- Bobby McFerrin (1)

- acapella (1)

- Snagglepuss (1)

- Intuit (1)

- TurboTax (1)

- Mint.com (1)

- budgeting (1)

- budget (1)

- b-word (the) (1)

- Morningstar (1)

- Ibbotson (1)

- SCHZ (1)

- SWLBX (1)

- VBMFX (1)

- Lehman Brothers (1)

- Chuck (Schwab) (1)

- Talk to Chuck (1)

- Hollies (the) (1)

- ponies (1)

- piggy bank (1)

- Amazon (1)

- Andrew Sullivan (1)

- bottlenecks (1)

- Gavin Newsom (1)

- Andew Sullivan (1)

- Radiohead (1)

- In Rainbow (1)

- Henrietta Lacks (1)

- HeLa cells (1)

- Gollum (1)

- my precious (1)

- Boiler Room (1)

- paywall (1)

- Washington Post (1)

- Dataligix (1)

- Epsilon (1)

- Axciom (1)

- Mark Wahlberg (1)

- Marky Mark (1)

- Mark Zuckerberg (1)

- Trojan Horse (1)

- DRE (1)

- life agent (1)

- contractors (1)

- realtors (1)

- Mr. McGuire (1)

- The Graduate (1)

- plastics (1)

- Eddie Arnold (1)

- SEO (1)

- Wikipedia (1)

- dogwalkers (1)

- UFO guy (1)

- SEO'y (1)

- TBToIBI (1)

- TBFoIBIA (1)

- Hindenberg (1)

- Gordon Gekko (1)

- probate (1)

- living trusts (1)

- revocable trusts (1)

- Napoleonic Code (1)

- Edwin Starr (1)

- lipsynching (1)

- War (song) (1)

- Louisiana (1)

- probate court (1)

- probate process (1)

- gift tax (1)

- CUSIP (1)

- NWUM fees (1)

- Bud Fox (1)

- magic dollars (1)

- Charlie Sheen (1)

- hourly fees (1)

- flat fees (1)

- passive voice (1)

- FRED charts (1)

- bear markets (1)

- Vladmir Putin (1)

- Richard Thompson (1)

- Linda Thompson (1)

- Information Week (1)

- Windows Vista (1)

- Windows 8 (1)

- WIndows XP (1)

- Marc Andreessen (1)

- Ameritrade (1)

- Datek. (1)

- DIY investing (1)

- Spiders (1)

- Qs (1)

- Wall Strret (1)

- day trading (1)

- hospice care (1)

- Guy Murchie (1)

- Joel R.Primack (1)

- sound of cicadas (1)

- cicadas (1)

- Jake Scully (1)

- Avatar (movie) (1)

- tall people (1)

- zeros (1)

- gladiating (1)

- Keystone Cops (1)

- FUBAR (1)

- SNAFU (1)

- medical journey (1)

- C corp (1)

- S corp (1)

- self-employment (1)

- say no more (1)

- U.S. Treasury (1)

- debt default (1)

- Stan Collender (1)

- Bruce Bartlett (1)

- lumpy revs (1)

- line of credit (1)

- Californa (1)

- Balance Sheet (1)

- Income Statement (1)

- Gene Simmons (1)

- lumpy revenues (1)

- predict (1)

- pre-dict (1)

- post-dict (1)

- Karl Rove (1)

- Ess Eff (1)

- hockey (1)

- mortgage rates (1)

- triangular lots (1)

- scale tales (1)

- Twitter IPO (1)

- Mexican Museum (1)

- Four Seasons (1)

- Socket Site (1)

- what-if'ing (1)

- maths (1)

- arithmetic (1)

- round numbers (1)

- linearity (1)

- Oliver Twist (1)

- No soup for you! (1)

- too much money (1)

- Jason Hull (1)

- Dr. McCoy (1)

- FAFNF (1)

- AUM (1)

- Motortrend (1)

- > (1)

- < (1)

- Ferrari (1)

- Isaac Newton (1)

- SF Curbed (1)

- TWTR (1)

- Investopedia (1)

- dutch auctions (1)

- Ferrari FF (1)

- V8 engines (1)

- V12 engines (1)

- IPO scandal (1)

- Tracey (1)

- Stockton (1)

- Vallejo (1)

- Socketsite (1)

- Friendster (1)

- MySpace (1)

- public offering (1)

- bubbles (1)

- 3/20/2000 (1)

- 8/15/2008 (1)

- BIT (1)

- fax machines (1)

- Mosaic browser (1)

- Marc Andreeesen (1)

- Barrows Hall (1)

- UC Berkeley (1)

- Lynx (1)

- 11/11/1993 (1)

- NCSA (1)

- Chambana (1)

- free (1)

- healthcare.gov (1)

- HITECH Act (1)

- ARRA (1)

- Stimulus (the) (1)

- Jennifer Garner (1)

- pre-Mosaic (1)

- Yardbirds (the) (1)

- Beatles (the) (1)

- zeitgeist (1)

- census (1)

- Houston (1)

- Virginia (1)

- zero-sum game (1)

- voting systems (1)

- Rand Paul (1)

- transfat (1)

- systems (1)

- variance (1)

- VA AG (1)

- statistics (1)

- bell curve (1)

- Batkid (1)

- Miles Scott (1)

- Cancer.org (1)

- IBC (1)

- TruthOut (1)

- Medi-Cal (1)

- Zuccotti Park (1)

- Occupy (1)

- Occupy movement (1)

- Batman kapow (1)

- 401k match (1)

- vesting (1)

- FPL (1)

- mulitplier (1)

- stimulus (1)

- Nick Gillespie (1)

- Reason.com (1)

- free money (1)

- Effie Trinket (1)

- steps per mile (1)

- petri dish (1)

- pertussis (1)

- whooping cough (1)

- match patch (1)

- Whole Life (1)

- Univeral Life (1)

- language fail (1)

- Taylor Swift (1)

- Alabama Shakes (1)

- Letterman (1)

- Hold On (song) (1)

- 4% Rule of Thumb (1)

- 6% Rule of Thumb (1)

- Rolling Stones (1)

- Joe McConnell (1)

- Sunol Grade (1)

- lemmings (1)

- oil wildcatting (1)

- Fugs (the) (1)

- George Clooney (1)

- monkey brain (1)

- Stevie Winder (1)

- Hogan's Heroes (1)

- drought of 2013 (1)

- Mont (1)

- collectibles (1)

- 49ers (1)

- smartned-up (1)

- Panthers (1)

- KISaSSYPGE (1)

- Punditracker (1)

- Big Four (the) (1)

- Titanic (move) (1)

- Jim Cramer (1)

- snake oil (1)

- Samsung (1)

- Tesla (1)

- financial media (1)

- iPhone 5C (1)

- iPhone 5s (1)

- football (1)

- Seattle Seahawks (1)

- Richard Sherman (1)

- Superbowl (1)

- violence (1)

- Peggy Lee (1)

- Geritol (1)

- job-lock (1)

- google bus (1)

- technology (1)

- indoor plumbing (1)

- Internet (1)

- fish gotta swim (1)

- ejection seat (1)

- Aston Martin (1)

- Sean Connery (1)

- Aston Martin DB5 (1)

- job unlock (1)

- a cappella (1)

- human capital (1)

- stress (1)

- bee's knees (1)

- Clint Black (1)

- Anya Schiffrin (1)

- Craig Kilborn (1)

- Cancer Institute (1)

- cancer staging (1)

- Paris (1)

- Andre Schiffrin (1)

- Manhattan (1)

- value-detract (1)

- Homer Simpson (1)

- Medicare Part C (1)

- Medicare Part A (1)

- Medicare Part B (1)

- jungle lasso (1)

- Sherrod Brown (1)

- Medicare for All (1)

- death tax (1)

- SOI (1)

- FPA (1)

- FPA SF (1)

- estate planners (1)

- appraisers (1)

- Karen Valentine (1)

- Austin Powers (1)

- oh behave! (1)

- Tucson Arizona (1)

- x axis (1)

- COD (1)

- Rush Limbaugh (1)

- EIB Network (1)

- Peter Fisher (1)

- AM960 (1)

- Felix Salmon (1)

- Slate (1)

- Michael Lewis (1)

- Flash Boys (1)

- GNH (1)

- Rush Revere (1)

- rushlimbaugh.com (1)

- NIMH (1)

- ADHD (1)

- Sandra Fluke (1)

- TheBigUs.com (1)

- Big Us (The) (1)

- CYA (1)

- legalese (1)

- boilerplate (1)

- hyper-fast-talk (1)

- FSIC (the) (1)

- asbestos (1)

- cancer (1)

- Pablo Picasso (1)

- HIPAA releases (1)

- CSW (1)

- holographic will (1)

- wills (1)

- trusts (1)

- living wills (1)

- Nolo Press (1)

- Maine (1)

- Michigan (1)

- New Mexico (1)

- Wisconsin (1)

- executors (1)

- guardians (1)

- bond (surety) (1)

- surety bond (1)

- Bali (1)

- deadlines (1)

- pre-commitment (1)

- Bullmastiffs (1)

- proximate cause (1)

- Basset Hounds (1)

- Saint Bernards (1)

- spam-evildoers (1)

- spambots (1)

- Alan Goldfarb (1)

- fee-based (1)

- fee-only (1)

- FP'er (1)

- business models (1)

- plumbers (1)

- shoes (1)

- shoe salespeople (1)

- insurance (1)

- vigs (1)

- vigging (1)

- ownership (1)

- cake-eating (1)

- vigorish (1)

- King of Assets (1)

- Queen of Assets (1)

- -Onlies (1)

- -Baseds (1)

- ALEC (1)

- LUST (1)

- Magnum P.I. (1)

- P.I. lawyers (1)

- whiplash (1)

- malingerers (1)

- totaled car (1)

- Hartford (1)

- Kelly Blue Book (1)

- KBB (1)

- Edmunds (1)

- NADA (1)

- cars (1)

- automobiles (1)

- Scorpion (1)

- scrap value (1)

- Michael Jackson (1)

- Diana Ross (1)

- Quincy Jones (1)

- Rover 2000TC (1)

- P.I. law (1)

- trade rag (1)

- trade magazine (1)

- trade mag (1)

- Rupert-Murdoch (1)

- Financial Times (1)

- Antwerp flashmob (1)

- Julie Andrews (1)

- Do Re Mi (song) (1)

- Sound of Music (1)

- Merriam Webster (1)

- bollix (1)

- hotchpot (1)

- punctilio (1)

- fightin' words (1)

- MS-DOS (1)

- Murdochian (1)

- IBD (1)

- Sire Pukes-A-Lot (1)

- TLAs (1)

- FP50IBD (1)

- WFs (1)

- Full Monty (1)

- churning (1)

- reverse churning (1)

- stockbrokers (1)

- stockbrokerages (1)

- Point A (1)

- Point B (1)

- DOS (1)

- wealthy folks (1)

- generalists (1)

- Google Machine (1)

- RIA (1)

- RIA-land (1)

- flashmob (1)

- Mark Knopfler (1)

- Wembley (1)

- Louis Armstong (1)

- Enron (1)

- Enron 401k plan (1)

- Janus funds (1)

- SMB market (1)

- handsome ransome (1)

- U.S. Congress (1)

- Carl Levin (1)

- Daniel Sparks (1)

- Timberwolf I (1)

- shitty deal (1)

- Goldman Sachs (1)

- rotten deal (1)

- CDOs (1)

- derivatives (1)

- Bogleheads (1)

- Solo 401k Plan (1)

- i401k plan (1)

- NGO (1)

- NGO'ed (1)

- Boomtown Rats (1)

- Bob Geldof (1)

- LiveAid 1985 (1)

- Aragorn (1)

- The Black Gate (1)

- bliss ninny (1)

- mortality (1)

- Romeo and Juliet (1)

- Comcast (1)

- AT&T (1)

- Verizon (1)

- SBC (1)

- PacBell (1)

- email addresses (1)

- nemesis (1)

- IT department (1)

- Yahoo! (1)

- gmail (1)

- Yahoo! Mail (1)

- Shades of Grey (1)

- true-dat (1)

- Internet domains (1)

- domination (1)

- email spoofing (1)

- spoofing (1)

- spam (1)

- database design (1)

- air-quotes (1)

- free advice (1)

- grace-provider (1)

- very-scary (1)

- luck of the draw (1)

- Brochures (1)

- SLN (1)

- Monterey CA (1)

- genie wishes (1)

- grin (1)

- MSK (1)

- friction (1)

- paperwork (1)

- New York (1)

- NYC (1)

- complexity (1)

- larding-up (1)

- private equity (1)

- speech therapy (1)

- physical therapy (1)

- gym class (1)

- parents (1)

- Will Robinson (1)

- Lost in Space (1)

- gym (1)

- PE class (1)

- Lisa Loeb (1)

- Stay (song) (1)

- beeps (1)

- bips (1)

- the Fed (1)

- AMT (1)

- Gretchen Wilson (1)

- country music (1)

- ton of tons (1)

- sunsetting (1)

- visibility (1)

- income averaging (1)

- tax shelters (1)

- lumpy income (1)

- tax fairness (1)

- tax complexity (1)

- tears (1)

- Bob Dylan (1)

- tears upon death (1)

- caregivers (1)

- mortal plane (1)

- midnight (1)

- 12:01 a.m. (1)

- dying moment (1)

- moment of dying (1)

- death tears (1)

- Goldilocks (1)

- Google Sheets (1)

- pricing theories (1)

- Google Suite (1)

- GOOG vs MSFT (1)

- magic numbers (1)

- MSFT vs GOOG (1)

- nit (1)

- gnat (1)

- Black Swan (1)

- Lehman Bros. (1)

- This Old Dog (1)

- NDIC (1)

- Bay Area (1)

- Italy (1)

- oil prices (1)

- piker (1)

- chalk line (1)

Not All Total-Bond-Fund Bond Index Funds are Alike

Tuesday, April 30, 2013 at 11amBy John Friedman

I read Morningstar’s annual report the other day, and saw something interesting in there: Morningstar’s business is being hurt by the rise of passive investment approaches and the mirror-image fall of active investment approaches.

That makes sense, right? After all, Morningstar helps folks be better informed about, primarily, mutual funds, and most mutual funds are about, primarily, active investing. So when passive is ascending and active is descending, that spells trouble with a capital T for morningstar with a capital M, right?

It also makes sense because quite a few people think that excellent mutual fund picking, like excellent stock picking, can be had via digging-in and doing the heavy-lift research, so as to divine which fund is likely to have the hot hand for the next umpty-ump years (is that future hot hand more likely to be attached to the fund with the hot hand right now, or the fund attached to the cold hand right now? Hmmm . . . . )

And that’s where Morningstar comes in: they help people research mutual funds, ranking them from 1 to 5 stars, with, to some folks’s surprise, 5 stars being really excellent (and rare), and 1 star being really terrible (and also rare).

So when passive investing — the opposite of active investing — is romping throughout the investing landscape and frolicking in the autumn mist, that’s bad for Morningstar’s business.

And so it was said, within M-star’s annual report Overview (yes, the Overview has no page numbers):

The investment industry continues to face challenges as assets flow to passive and fixed-income products.

as well as this in the Letter to Investors (Page 4):

It’s no secret that 2012 was a challenging year. In addition to a lackluster global economy, the investment industry has been hurt by low interest rates, client risk aversion, and increased regulation. And, for many firms, the popularity of passive products and alternative investments is a major challenge. This often leads to lower revenue expectations and higher expenses, so asset managers and brokerage firms tighten their belts. For us, this means longer sales cycles and smaller price increases. It’s also tough to get clients to try new providers.

Apparently lawyers like the liability-containment characteristics embedded within the DNA of the word-family-tree, challenge/challenged/challenging, eh!?

And then there was this, too, addressing a fall-off in the part of their business tied to traffic on its website (Page 11):

Meanwhile, the popularity of passive and fixed-income investments means less interest in research on stocks and actively managed funds. Nevertheless, our site continues to garner positive reviews.

What I think happened here is that M’star wanted to say that its website business had also been challenging, but that it shied away from doing so because its analysis of the remaining inventory of the challenge/challenged/challenging sibs led it to conclude that it was best to not narratively sup at that particular word-family’s trough again.

So everywhere it looks, M’star sees passive investors and their diminished interest in all the data M’star has collected, coddled, coagulated and collated (and sometimes simply purchased, e.g. the Ibbotson data) and which it now sells.

Full disclosure: I am a shareholder (that’s why I had the annual report handy . . . ). I think a lot of Morningstar, though less than I once did, and these days I am mostly selling off my single stock holdings in favor of . . . passive investments! So the M-star shares might be vamoosed soon.

* * *

The other day I was doing some portfolio design work with a client and we were looking at Schwab’s passive index U.S. bond offerings. For reasons I won’t bore you with, we wanted something from Schwab to fill that role other than SCHZ, its very groovy, very free-to-trade-at-Schwab ETF designed to track the entire American bond market.

So we were looking at SWLBX, Schwab’s Total Bond Market mutual fund, using Yahoo Finance as our main tool (Google, you were too late; the old dogs — me, anyway — had already learned how to do what they needed to do on Yahoo Finance, so our imprinting was complete and the bonding was cured by the time you came along).

And there I was, doing what I normally do, which is to do a quick check of this unknown-quantity/stranger-fund against other known quantities, such as VBMFX, which is Vanguard’s similarly named fund, when, with but a few clicks, good golly Miss Molly did I ever see something that surprised me.

First I saw this (all pix scraped from Yahoo Finance on 4/15/13):

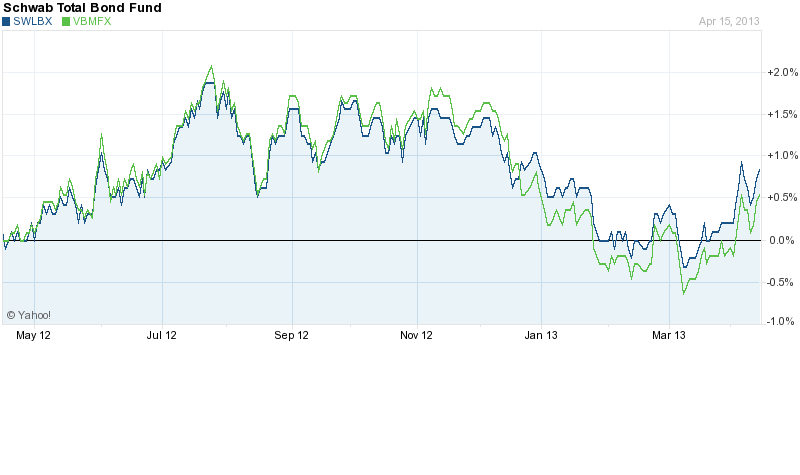

Share Price of Schwab Total Bond Fund vs. Vanguard Total Bond Fund,

over the most recent one-year time period

That looks about right: the green line, which represents the Vanguard fund, is closely tracking the blue line, which represents the Schwab fund, and vice versa (necessarily vice versa, right? — both are tracking the same thing, which is the overall American bond market, so they should both behave the same). But there was enough discrepancy, particularly towards the recent, right side of the graph, that I wanted to see more.

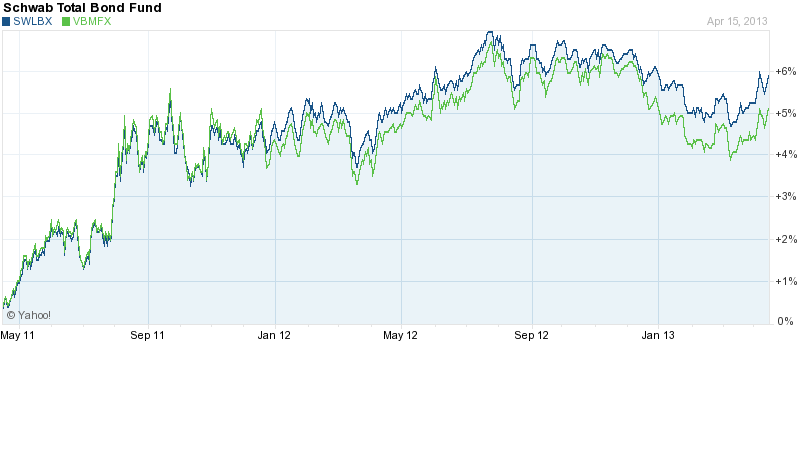

So I dialed in a two-year time frame and this is what I saw:

Share Price of Schwab Total Bond Fund vs. Vanguard Total Bond Fund,

over the most recent two-year time period

Again, it’s pretty tight, but, also again, the more recent time period shows a lot more disparity than the older time period, to the left of the graph, which is tight as a drum. My curiosity was piqued (to say the least), though not yet even close to peaked. So I dialed in a five-year time frame and this is what I saw:

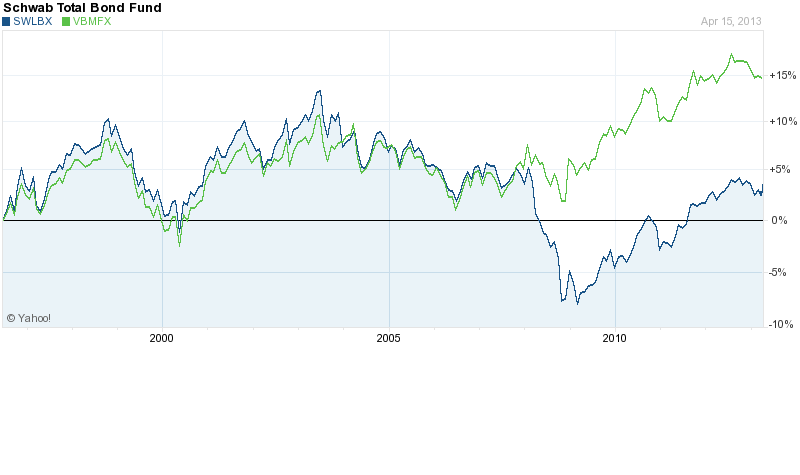

Share Price of Schwab Total Bond Fund vs. Vanguard Total Bond Fund,

over the most recent five-year time period

And that made me do a Huckleberry Hound Dog double-take. What on gosh’s green earth happened in 2008? Yes, September the 15th happened, with Lehman going bust and the credit markets kvetchin’ and a’ retchin’, but this is a side-by-side comparo of two passively invested total bond funds, both designed to reflect the entire American bond market, in all its many facets — warts and pimples and zits and all, as well as beautiful eyes and high cheekbones and slim waists and all — and which should both, therefore, presumably, be quite similarly impacted. Both, after all, are designed to reflect the good, the bad and the ugly of the American bond market.

Yet there is the Schwab fund (the blue line) taking a much bigger hit to its share price and never recovering versus the Vanguard fund (the green line).

Stunned and staggered, I went there and dialed in the maximum time-frame version — the longest time-frame Yahoo Finance’s static chart tool (the old, scrapable version) was willing to serve up, and this is what I saw:

Share Price of Schwab Total Bond Fund vs. Vanguard Total Bond Fund,

over the maximum most recent time period Yahoo Finance offered up on April 15, 2013

Pretty vivid, eh? Both funds are supposed to be tracking the exact same single thing, but they are so very different at that one point in time that, clearly, one or the other of them — or perhaps both? — failed to track that one single thing.

* * *

So say you own $10k of each fund, and say that you’re going along and you’re going along, and they are always within a nit on a gnat’s knee’s distance from one other, in near-perfect lockstep, so that when one is up to, say, $12,345, the other is up to, say, $12,456 or so, and they are really tightly tracking each other, but then one day, when the markets are going crazy in the fall of 2008, all of a sudden, after years and years of tracking each other snug as a bug, one of them loses 13% of its value while the other is losing just 3% of its value. Kaboom!

Your $12,345 worth of the one fund goes all the way down to $10,740.15 (that’s the 13% loss) and your $12,456 of the other fund goes down to $12,082.32 (that’s the 3% loss), with the former losing $1.6k and the latter losing about $375.

And say that all of that happens in the course of a few weeks, and that, once that big divergence is over, from then on things go back to the way they were, with the two funds tracking each other snug as bugs are snug, never more than a nit-gnat’s-knee’s difference between what they do each day, but always and forevermore with that 10-plus-percent delta between them. So where once they danced the tightest of tangos, now they peer at each other across a wide chasm, two lovers never again to touch.

So remember, all you passive investors out there: not all passive portfolios behave the same, and this is true even when the passive portfolios are supposed to be passively tracking the same thing.

* * *

Oh yoohoo! Yoohoo! Oh Morningstar! There is still plenty for you to say about funds, even if they do all end up being passively managed. Because, as it turns out, one or more of them will fail at tracking their chosen target — one or more of them will end up having some wriggle room in their target that no one would’ve guessed was there, given their name and their marketing materials.

Which is not to say that I’m sanguine about your business, M’star. The passives are a’risin! Maybe you all should be thinking about buying an ETF-data house?

* * *

Note to wonkish readers and rocket science money guys and gals: do you know what caused the divergence? I haven’t the time to dig into it.

Did Schwab have auction rate securities in there? Dunno. But if they did: gosh!

Or maybe it was some sort of weird distribution that the Schwab fund made but as to which Vanguard did nothing even remotely similar? That can make for some big, unilateral downdrafts in the price of the shares of the fund. That might be easy enough to look into . . . but I haven’t the time or desire to do it.

My hunch and gut — and it’s only that — is that Schwab larded up its total bond fund with something that proved to be . . . unbecoming . . . let’s call it. But that’s probably my pro-Vanguard, suspicious of Chuck approach to the Financial Services Industrial Complex generally.

Clearly Schwab had some nasty potion of some kind in its fund that Vanguard did not — something that led to the Schwab fund having to digest something that the Vanguard fund did not.

But all of this begs the real question here: which fund best represented the American bond market?

Surely some fixed income folks know the answer to this question off the top of your heads. Me? I’m the generalist. Any specialists out there who can lend a hand? Any bond gurus who can shed some light on this apparently permanent delta?

At least one inquiring mind wants to know. Thanks for any insights you can provide!

Good info. Lucky me I discovered your blog by accident (stumbleupon).

I've saved as a favorite for later!