Big Machines

Tuesday, November 6, 2012 at 11amBy John Friedman

Twenty years ago, at the dawning of the commercialization of the Internet, someone described the POTS (the Plain Ol’ Telephone System) as the biggest machine ever made. It spanned the globe. It reached into virtually every home and business in the developed world. And it was all one — it was all connected into a single huge thing.

This was before widespread use of mobile phones. Once those little fellas were added on top of the POTS, both a physical layer and a non-physical/wave-connected layer combined into an even bigger machine — the NSPOTS (the Not-So-Plain-Ol’ Telephone System).

And mixed in with all of that came the tubes that were the Internet, coming together to form an even more marvelous machine — the NSPOTSWIT! (the Not-So-Plain-Ol’ Telephone System with the Internet on Top!).

So today you have people using mobile phones to do billions of dollars’ worth of secure commercial transactions via the NSPOTSWIT!, including, it’s important to note, transactions that are hooked in, quite directly, to all the money in all the banks and in all the financial institutions in the world.

Having worked at one of those institutions, I can vouch for the fact that there is a layer built into the connection between the institution and the NSPOTSWIT! that is very, very serious, where the very, very best engineers do their very, very best work, to make sure that no one breaks in and takes all the money (or, in some ways, the even worse scenario of scrambling all the data indicating who owns all the money . . . aaarrrrghhhh!).

So, today, we have the plain ol’ telephone system, brought into the Twenty-Teens as the not-so-plain-ol’ telephone system with the Internet on top!, handling some mission critical (to put it mildly and to say the least) functions of our world.

* * *

Speaking of which, have you seen how well our vote-taking and vote-tallying system is performing?

Oops. That picture is from 2008. How ’bout this one?

Ooooops again. That one’s from 2004. How ’bout this one?

Yup: that’s today.

Time will tell how much time it will take the unfortunate few to vote today. Yesterday, though, we had reports of some people in FLA having to wait in line for eight hours to exercise the franchise.

The whole voting process works just fine in Ess Eff CA, as it does in most places, which is not surprising because this is a task at which we have the ability to be perfect or near-perfect, as in Three-9s and the like. But then some places — specific places — do a bigtime fail on this stuff. BigBigTime, ladies and gentlemen, BigBigTime.

* * *

This is the holiest of holies, this voting stuff, yet in some places it’s being dragged through the mud.

We drag it through the mud.

We’ve had great calculating machines in our lives for — depending on how you count — at least 30 years. And the iTubes have been bulked up and fortified for at least ten. This shouldn’t be all that difficult compared to, say, putting the NSPOTSWIT! together in the first place. After all, we’re good at building Big Machines, right? Some might even go all patriotic on this point, and say that, when it comes to building big, excellent machines, like the POTS and all that came after it, We’re Number 1! So let’s build it, shall we?

* * *

As we get older and wiser, we hopefully experience feelings of embarrassment less and less, because we get better at knowing what will embarrass us, and we get better at not doing those things that will embarrass us. It takes both time and awareness . . .

Today the whole world is watching. If yesterday is any indication of what today will be like, today will be a day of embarrassment for all of us.

Blushing, we look downward and, ten-year-old like, we avert all others’ glances.

So shame on anyone who acted on even the slightest hint of a desire to hinder anyone from voting — shame, plus some criminal fines plus some loss of freedom plus some being-made-an-example-of.

* * *

Let’s hope that the embarrassment we feel today about our rickety ol’ vote-taking and vote-tallying machinery is overshadowed by an otherwise wonderful day.

And then let’s improve the machine, shall we? Let’s build it.

* * *

I don’t often mention people in these pieces, or make dedications. But today I do.

This piece is for my lovely spouse, love of my life, who is a far gentler, far kinder person than I am, and much less prone to anger, but who happens to get very, very angry about this stuff. This one’s for you, babe; let’s hope that four years from now we’re looking at lots of good news on the long-voting-line front and you won’t have to get angry about it!

774 words (about an eight minute read sans links)

Some Words About the Election, and About U.S. Economic Performance Under the Two Parties

Monday, November 5, 2012 at 11amBy John Friedman

Every single component of a person’s life has a financial component to it. Now, I’m not saying that this is a good thing or a bad thing, but I *am* saying that, in the world in which we live, this is a true statement (see the video of me talking about this further).

For years I’ve been asking people — anyone who would care to listen and receive a question and think on it and respond — to come up with some aspect of their life that does *not* have a financial component to it. To date, 100% of those people have tried in vain to come up with an example.

So if you have an example — please! — let me hear it. It’d be really great to know that somewhere out there is something in someone’s life that is somehow outside the realm of the financial — something that exists in your world and that is 100% a-financial.

* * *

This week’s election clearly lives and breathes in the financial part of all of our worlds. The candidates have said so, and then there’s Carville’s oft-repeated it’s the economy, stupid — the internal (and then external) tagline from Bill Clinton’s successful 1992 run against GHW Bush. And then there’s every talking pundit-head’s focus on the unemployment numbers. And the list goes on. And on and on.

Anecdotally, seemingly every everyday-Joe and everyday-Jean the media interviews says they’re voting for their given vote-getter because he (no shes involved . . . yet) will be best for the economy.

It’s interesting that people — sincerely, I believe, with rare exceptions — differ so much on which candidate would, in fact, best for the economy. It’s also interesting that, for most of us, it’s entirely self-evident which candidate that would be — even though something like half of everyone else in the country disagrees with us!

* * *

Folks in the Financial Services Industrial Complex tend to be a bit more conservative than the public at large (and that is probably . . . a conservative characterization of the degree to which people in the FSIC are conservative). Right now I don’t have linkable data to support that claim, but I do have . . . a gut feel for it! . . . and I suspect that, if I took some time, I could find that data within a couple of hours. But not today. Other things to do.

Most folks in the FSIC do not, however, put that information out into the world at large, because doing so can alienate a good chunk of their prospecting base.

A few, though, do. They put it out there.

* * *

Larry Doyle came through my Internet browsing yesterday, via an article entitled Why I am Voting for Romney. I haven’t the time to figure out Mr. Doyle’s place within the Financial Services Industrial Complex in any detail, but it looks like he mostly FSICs in the media end of things, and recently opened up an investment advisory firm. Mr. Doyle’s article makes it clear that he is very, very much in favor of a Romney presidency, and very, very much against a continued Obama presidency.

My hunch is that anyone who is voting for Obama would look at the Five Points (is there a theme here?) Mr. Doyle uses to support his case and disagree 180 degrees with Mr. Doyle’s thoughts (briefly, the five are: Romney is better for (1) the economy and (2) the military and (3) the free exercise of faith, and would (4) respect the rule of law and not violate property rights, all of which would (5) take us forward while the other guy would take us backward).

* * *

I rarely step out from behind my a-political curtain, but I think today is an appropriate day to do so.

In keeping with the subject matter in the John Friedman Financial Blog, I’ll only comment on the first point Mr. Doyle makes: I am 100% confident that the Republican approach to the economy has been a disaster. Favoring capital over labor has not worked; favoring stuff over people has already been very, very bad for people and is heading in the direction of getting worse and worse for stuff.

I am also 100% confident that the reason many people think the Republicans are good at the economy has nothing to do with them being good at the economy, and everything to do with Frank Lutz and the Republican Party’s vast superiority at messaging (George Lakoff is no Frank Lutz) (and could George Lakoff be a good George Lakoff if he were as good as Frank Lutz?).

I could go on (who is better on defense comes to mind as being a place I’d otherwise like to go . . . ) but let’s stick to the financial realm, shall we?

There are plenty of graphs out there numbering-up which party is better for the economy. Most of them seem to be at least a bit cherry-picked, i.e., to support the notion that Republicans are better for the economy, it helps to compare periods during which each party controlled Congress while, to give the nod to the Democrats, it helps to compare periods during which each party had the presidency.

So that’s not much help.

But how about looking to a source proclaiming against its traditional interest? What would it mean if Fox Business, which, as part of Fox, most people would agree is Republican-leaning, published an article stating the Dems are better for the economy?

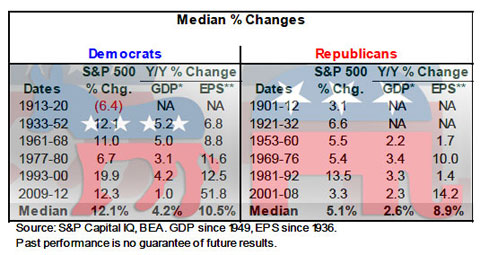

Here is what Matt Egan, writing an article in Fox Business called, History Shows Stocks, GDP Outperform Under Democrats, found, when looking purely at (a) the S&P 500 (which is a measure of how the prices of the stocks of a big chunk of the American stock market — a chunk that includes most big American companies you’ve heard of — have done), (b) Gross Domestic Product (generally, and lay’y, the size of the economy), and (c) Earnings Per Share (a measure of the profitability of businesses):

If you find these numbers wrong, there are plenty of others that you will find right. But please do not put them into the same place, lest you have a matter/anti-matter explosion, as in, these two things cannot coexist

* * *

So please do vote. It will have an impact on your overall financial health. It really, truly, will.

And now excuse me while I step back behind my a-political curtain.

1003 words (about an 11 minute read, sans links)

Language-Fail in the Land of Financial Planners

Friday, November 2, 2012 at 2pmBy John Friedman

Did you know that there is a big difference between a fee-only financial planner and a fee-based financial planner — that this simple, single-word swap of the word only for the word based means a great deal in the land of FPers?

No? Well, you can read all about it on the Internets Tubes via the Googles, and also in the brief summary a few paragraphs down below.

And did you know that, in general, the F-O FPs do not look kindly at all upon the F-B FPs and vice versa, and also that there is a gosh-awful regulatory and legislative big-time rumble going on between the F-Os and the F-Bs (and, for that matter, also the B/Ds and the RRs and FINRA and the SEC and the Dems and the Repubs and the lobbyists, and the list goes on and on and on . . . )?

No, right?

Pretty much no one outside the industry knows this stuff: it’s inside baseball and quite technical and boring to most (hence no links to the details), but it’s inside baseball that just so happens to touch every single person’s life, at least tenuously and often significantly, because the baseball we’re crawling inside-of constitutes a decent-sized chunk of the Financial Services Industrial Complex, and because the FSIC touches every single person’s life (except for those like the late Chris McCandless) every moment of every day.

* * *

Briefly, the fee-only folks make their money via nothing but . . . wait for it . . . fees, while the fee-based folks earn commissions as well as fees.

In practice, what this usually means is that fee-only folks make their money by charging Assets Under Management fees (typically in the neighborhood of 1% per year of the money they’re managing for you) while the fee-based folks are usually happy to go the AUM route (it is, after all, a very sweet business model), but also are happy to sell you insurance and annuities, and many are also happy to buy and sell for you stocks and bonds and private placements and other products — all of which generates commissions for the fee-based financial planner.

And, oh, the commissions! Ask the insurance agents in your life what their percentage commissions are . . . because I’ll bet you dollars to donuts they never offered up that information (note that Friedman’s Law of the First Thing, as applied to the initial courtship at the front end of a commercial relationship, is that you should never do business with anyone who either actively or passively, at any time, hides from you the amount of his or her compensation).

* * *

Now I spent a bit of time trying to figure out how these F-O vs F-B labels came to be, and who came up with them, but my search came up dry. I think I once heard about how it all came to be, but the recollection is all fogged over . . . (please let me hear from you if you know the origin story).

But I *can* tell you this: the labels are total failures. I have never, ever met anyone who knew the distinction (other than people in the business) and, what’s worse, I have never known anyone who, after learning about the distinction, could explain it to you an hour later, let alone a day later.

Yet the financial planning industry by and large makes its bed with these labels and with this unhelpful language.

* * *

And how about the also confusing language of investment advisors vs. financial planners? That’s another one that’s not doing people any favors in terms of one of the important functions of language, i.e., providing useful shorthands that are easy to remember, and that replace long unwieldy language.

Today, constrained by time as I am, I have but two things to say for now on this topic (and many more in the future).

First of all (and I do truly love this fact), investment advisors can’t even agree on how to spell the word adviser/advisor!

This much is clear: if you look at the laws that apply to our work, they all use the version with the E. So, too, for the spell checker built into the software into which I type.

A lot of us, though, including me, use the O version. I don’t know precisely why, but I just like the O version better (just because . . . ). And all the language enforcers out there say that either version is acceptable.

So we start with a word that is, spelling-wise, two-faced, ambiguous and ambidextrous.

* * *

Second of all, many (most?) people do not understand the difference between financial planners and investment advis[oe]rs.

For example, when I tell people that I’m a financial planner, the thing that at least half of them hear me saying (literally hear me saying, as best I can tell) is, I’m an investment advisor, judging by the fact that the first thing out of their mouths is, What should I invest in? and Where’s the market going?

Chalk up a victory for the part of the Financial Services Industrial Complex that butters its bread via people focusing laser-like on investing — and a big fail for people like me who will tell anyone willing to listen that investing, while often playing an important role in many people’s overall financial well-being, is, more often that not, *not* in the Top 5 determinants of their overall financial well-being (numero uno, I say again, and as I will say again and again and again, is savings rate).

* * *

To begin laying out the confusing state of the language, let’s start with this startling piece of linguistics-meets-regulations gymnastics: financial planners just about always have to be regulated as Investment Advisers, even if they don’t directly manage money for people.

To give you an example close to home, I do not directly manage money for people, but because I do give advice about how to invest, and do so in some detail, I am regulated as an Investment Adviser.

As it happens, a lot of people who do nothing but manage money for people and are compensated via Assets Under Management fees are also regulated as Investment Advisers (if instead someone simply executes buy and sell orders for customers, and is compensated via commissions for doing so, then s/he is acting as . . . sorry to have to lay this whole thing out, but this is the language . . . a Registered Representative of a Broker/Dealer, which is what most people call a stock broker).

Financial planners, on the other hand, help people plan — they help them figure out where they are, where they want to go, and how to get from here to there. Technically, if they never talk about investments, they need not be subject to any licensing at all, though, in practice, most financial planners are compensated via Assets Under Management fees and earn their keep via managing money).

* * *

With that I’m over my word limit, and so I’ll have to save for another day — maybe next week — writing up some thoughts about better, more easily understood language which we all can use and which people everywhere can easily understand, as well as some thoughts about what it means when financial planners provide value by providing financial planning services while simultaneously being compensated as money managers.

A good weekend to all, and may all the subways of NYC — heartbreakingly broken right now to those who love the people-made world as well as the natural — be up and running right soon.

1,106 words (about a twelve minute read sans links)

Everyone has a Financial Life

Thursday, November 1, 2012 at 11amBy John Friedman

After some much needed time off, I’m back and, right off the bat, find myself wanting to write about something that came up during San Francisco’s Financial Planning Day, which happened on the 20th of last month (hello November! — it used to seem like you were a million miles away, and, by gosh, here you are already).

Financial Planning Days are a joint effort of the financial planning powers that be (the Certified Financial Planner Board of Standards, the Financial Planning Association, etc.) and various locales.

SF’s Financial Planning Day happens once a year, at UC Hastings College of the Law; the event is thoroughly imbued with the local financial planning powers that be (the FPA of San Francisco and the city’s very own Office of Financial Empowerment) (yes, EssEff CA does have such a thing, and I think it’s a great thing for the city to have, and, yes also, I’m fully aware that, to an Ayn-Randian sort, this office might sound like a very foolish thing, right up there with the over-the-top-Randian name for California’s sales tax authority, which is the Board of Equalization, a name with which even I have a hard time).

Going on at the same time that Saturday in nearby Civic Center plaza was some X-bike thing. Bikes flying to and fro’ all over the place (with the bike riders mostly, but not entirely, aboard for the flights). Tattoos everywhere. Lots of pot aromas filling the air. And all in the name of Mountain Dew. Ain’t the little city by the bay grand . . .

* * *

So, picture, if you will, a big, ugly building (sorry, Hastings, but you don’t look mahhhhrvelous; you were built during the period of nearly-universally-ugly school building construction). And picture also, inside the big ugly building, a big, ugly room that’s full of planners and plannees, going on all day, with hundreds of 30-minute one-on-ones going on between planner and plannee, coupled with a steady stream of group presentations going on in the class rooms. The public is invited, and anyone can get a half hour of free financial planning advice from some excellent planners.

* * *

I did a prezo on Intro to Financial Planning, and, like they say, and as is so true, you learn a lot by teaching.

My learning moment came at the beginning of my prezo, as, looking up into the classroom (it’s one of those amphitheater-type classrooms, in which the teacher area is as much as ten or fifteen lower than the student area), I decided then and there to wing it a bit on the first things I said.

And out of my mouth came, pretty much fully formed out of the unconscious, something I suspect I’ll be working into my language — something I am currently calling the Financial Planning Quasi-Syllogism (“quasi” in that it looks like a syllogism, but I suspect a logician would tell me it t’ain’t no such thing).

It goes like so:

1. Everyone has a financial life.

2. Everyone has done some of their own financial planing (because, inside of their financial lives, everyone makes decisions on a daily basis, virtually all of which have some future impact, and because making decisions that have some future impact is what financial planning is all about).

3. Just about everyone could use some help being smarter in their financial life as they go about doing their own financial planning.

* * *

Sound basic? Elementary? I agree, but I also think there’s something here that’s worth thinking about — both for me as a professional, as I go about helping people smarten-up in their financial lives, and for you, reader, and everyone else as well, as you go about living inside your financial life, doing your own financial planning, and hopefully finding this quasi-syllogism language useful when you’re thinking about how to be happier in your financial life and/or when you’re considering getting some help in this part of your life.

Consider, then, the FP quasi-syllogism as a work in progress. I’ll keep you posted on how the language morphs and filters through my work.

Until then, know this: you are doing your very own financial planning. How’s it going for you?

* * *

Two other thoughts, one about FP Day and the other about the first statement of the three statements that make up the quasi-syllogism:

1. FP Day Thought. A room full of planners is, for me anyway, a fun room to be in (I did not usually feel this way when in a room full of lawyers).

2. Poking and Prodding the First Statement of the Quasi-Syllogism. For years I’ve been looking for a good example of someone who, in modern times, did *not* have a financial life. The best example I’ve come across is Christopher McCandless, the true life subject of the book and very excellent movie, Into the Wild, who, as a young man, moved to a remote part of Alaska without much in the way of survival skills, carrying with him just 10 pounds of rice and a rifle with some ammo and a few personal possessions, and who appears to have died not soon thereafter from lack of food coupled with a fateful decision to eat some poisonous berries.

When his remains were found, the searchers also found $300 in Christopher’s wallet — three hundred totally, utterly, irretrievably useless dollars, because Christopher had, indeed, stepped out of his financial life and altogether out of the financial world, thereby rendering, as applied to Christopher, the first statement of the quasi-syllogism untrue.

Out in the middle of nowhere in Alaska, then, the financial planner/plannee in all of us had best spend time smartening up about berries. For the rest of us, it’s dollars that bring us the food we eat, and smartening up about the dollars parts of our lives is way, Way, WAY worthwhile. If, that is, you like eating food.

889 words (about a nine-minute read, sans linked content)

It was 25 Years Ago Today

Friday, October 19, 2012 at 10amBy John Friedman

I was 11 when Sgt. Peppers came out. I had mumps. I also had my first good stereo (a passion which continues to this day). I listened to the album many, many times. I have vivid recollections.

These days I listen to Sgt. Peppers only very rarely (partially because many Beatles CDs sound terrible, with the remastering meister putting all the vocals in one channel and everything else in the other) (why dey do dat?).

In any event, whenever I hear about an anniversary that has a twenty in it, I cannot help but sing to myself, It was twenty years ago today, or, in today’s case, It was twenty-five years ago today.

* * *

It was 25 years ago today . . . that I was at 721 Lighthouse Ave. in Pacific Grove, working upstairs with the inimitable Edward downstairs, when some sort of ruckus brought me downstairs, and the almost-equally-inimitable Shelley said, Have you heard? The market’s crashing!

Indeed it was. Without looking it up, the numbers that live on in my memory and in infamy were 500 points down on the Dow, and down 25% for the day [note from later on: after writing this piece I looked up the numbs, and this is ballpark correct: it was 508 points and 23%].

On today’s Dow that same 25% drop would be about 3500 points.

So picture, if you will, that, today, around noon on the West Coast (3 pm on the East Coast) you hear that the Dow has dropped 3500 points. Yikes!, right?

Even people who are not market-oriented people (e.g. people who do not know what the Dow is, or who, when they hear the phrase, the market, don’t necessarily hear the word stock as the implicit modifier of the word market) might even stop and stare, take notice, and think, Gee, that sounds like a lot.

It was.

* * *

I leave it to the market historians to talk about the significance of what we now know as Black Monday. There will surely be articles galore everywhere today.

Instead, let’s talk about the time frame of it all, and about being a smart consumer of financial services in the money manager realm, shall we?

And let’s do that by, first, comparing how to be a smart consumer of financial services in the money manager realm to how to be a smart consumer of financial services in the estate planning realm. You’ll see why in a moment . . .

* * *

When I help clients get their estate planning done (it’s way-hard for people to contemplate their own demise, so it’s way-hard to get wills and trusts and such done!) my advice to them is that the ideal estate planning lawyer they’re looking for is someone (a) with whom the client can stand being in the same room for some hours’ worth of time (note to estate planning lawyers: this is a major filter), (b) who does nothing but estate planning (estate planning, if other than very basic estate planning, is not a good place for half-timers and general practitioners to ply their generalism), (c) who has been doing estate planning for at least, say, a decade or two (because inexperienced lawyers are dangerous), and (d) who is at least, say, a decade or two younger than the client (because, to use the word that most people first experience when looking for the first time at a binder full of estate planning documents, the client wants to predecease the client’s estate planning lawyer, so that their lawyer can put into effect the client’s estate plan that the lawyer wrote).

So you want someone who is experienced, but not going away any time soon. You want them to be in that just right happy medium.

My advice for people seeking money managers is somewhat similar, but with one important distinction relating to price, driven by the different pricing models estate planning lawyers and money managers use.

Most estate planning lawyers base their bill on hourly fees; the more experienced the lawyer, the higher the fee (and, maybe, but maybe not, the more efficient the lawyer can crank out your documents).

With money managers this is seldom the case. Most money managers (MMs from here on) charge AUM fees (Assets Under Management fees) rather than hourly fees. Likewise, most MMs require that you have your money someplace where they can have some control over your account, so that they can buy and sell investments on your behalf and, also, so that they can pay themselves out of the accounts they are managing.

This they will do. They’ll typically go in there and snag about a quarter of a percent of your account each quarter, and thereby pay themselves annual AUM fees of about 1% of your investments.

Yup, that’s right: the MM industry has one of the most beautiful business models around, given that it (a) uses a very standardized, no-two-ways-about-it, mathematically-calculated fee, which (b) their clients never have to actively pay to them because the MM sets up the account to auto-ding the fee from their client’s accounts into the MM’s own account. Think about it: most MM clients never have to pull out their checkbook and write a check to their MM to pay the MM his or her compensation. Nice eh?

* * *

There is precious little price competition on AUM fees. So when I see a skilled MM who actually appears to be price competing, I congratulate the MM and keep that MM in mind as someone I’d like to get to know more.

Instead, the main variable MMs use to discriminate among potential customers is account minimums (minima?), i.e., very good MMs might have account minima of, say, $5 to $10 million, while a lot of everyday, run-of-the-mill MMs are pretty thrilled to see accounts above $250k.

Yes, many, many people cannot have an MM in their lives because the MM industry does not, by and large, work with normal people with normal asset bases.

Even then, though, if you look at their pricing schedules, you’ll see something that pays homage to a 1% center of gravity in the AUM fee universe.

* * *

These days it’s very easy to see any MM’s pricing schedule. You need only go to the IAPD, which is the Investment Adviser Public Disclosure website. Once you get to the site, the gossipy/how-big-is-that-fish-you-caught parts you probably want to go to right away are what I call The Item Fives: i.e., Item 5.F of the main form, which shows the amount of assets the MM has under management, and, a bit harder to get at, Item 5 of the MM’s Brochure, which shows the MM’s published price schedule as part of a pdf file that’ll pop up once you start clicking your way through the Part 2 Brochure click-trail.

This’ll all make sense when you look at the nav bar on the left once you have selected an MM to research.

* * *

By the way, I am not an MM. I don’t manage money for people directly. Instead, I either (a) help them do their own money management (just about everyone is surprised how easy, simple and low maintenance doing so can be . . . and how terrifically empowering it feels to do it), or (b) help them be smart about hiring, managing and, if need be, firing their own MM.

* * *

Since most MMs charge fees that are, mostly, in the same ballpark, you owe it to yourself to get someone who is very experienced. Why pay roughly the same price for someone who is inexperienced?

The same can be said of most real estate agents. They all charge roughly the same thing, more (commissions for commercial leases in SF) or less (residential sales commissions in SF have seen some variability over the past five years)

* * *

So today my advice for everyone with an MM in their lives has a historical wrinkle to it: ask your MMs what they were doing on Black Monday.

If they have good stories to tell — what it taught them, where they were, how they and/or their supervisors handled it, etc. — that’s good. And if they don’t? Well, you have someone who wasn’t in the industry twenty-five years ago.

That might or might not be a bad thing; I leave it to you to decide.

So, yes, I admit it. I’m an agist to a certain extent — especially when the battle-tested folks can cost roughly the same amount as the people just getting started, who weren’t even around for the minuscule-by-comparison Flash Crash on May 6, 2010.

1,280 words (about a fifteen minute read sans links)